Five Questions About the Fed's $4.5 Trillion Balance Sheet

Five Questions About the Fed’s $4.5 Trillion Balance Sheet

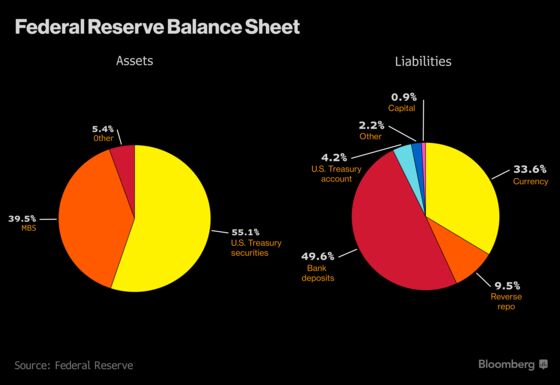

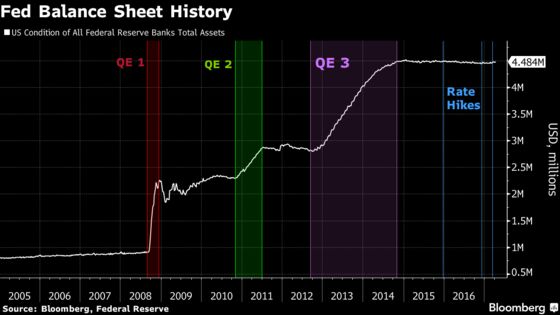

(Bloomberg) -- The Federal Reserve is getting ready to "normalize" the size of its $4.5 trillion balance sheet.

A lot is at stake. Simply maintaining that over-sized stack of bonds makes the Fed a big player in the markets for Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. Investors and traders are anxious for information about how the central bank intends to pull back.

"There are so many different parameters by which they could set this process," said Tom Simons, a senior economist at Jefferies LLC in New York. "There's a wide range of market implications as a result for what the public supply of Treasuries is going to be and how liquid the MBS market is going to be."

What we know so far

At the moment, when a bond in that portfolio matures or gets paid back early, the Fed reinvests the returned principal. To shrink the balance sheet, all the Fed has to do is stop reinvesting.

But the idea of halting that process all at once makes the Fed nervous about possibly disrupting markets. Stopping now would shrink the portfolio by about $280 billion over the last seven months of 2017, and by about $650 billion in 2018, according to Walter Schmidt, the Chicago-based senior vice president at FTN Financial, and data from The Yield Book.

At their May meeting, policy makers backed a plan to reduce each month's reinvestments by a set, and as-yet undecided, dollar amount. That sum will roll off the balance sheet and any maturities above the cap will be plowed back into the market. As long as that goes smoothly, the cap would then rise every three months until it reached a ceiling, or steady state, of monthly run-offs.

That still leaves a number of crucial unanswered questions.

Question 1: When will the draw-down start?

Fed officials have said they favor getting started in the second half of this year, but they probably won't want the first move to coincide with an interest-rate hike. And they're on course to lift rates two more times this year.

In the New York Fed's latest survey of primary dealers, respondents thought the Fed would most likely move forward with rate increases in June and September before beginning to trim the balance sheet in the fourth quarter.

If the start time for the run-off moves up to September or before, expect the second of those rate hikes to be delayed.

Question 2: Where will the Fed set the caps for monthly run-offs?

A few weeks ago, many economists were predicting the Fed would kick off the process by shedding about $20 billion a month. Those estimates have been dropping, especially since the Fed revealed that it favored phasing in the roll-offs.

Roberto Perli, a former Fed economist and partner at Cornerstone MacroLLC in Washington, expects the first cap to land at $10 billion, rising by $10 billion every three months before settling after 15 months at a steady state of $60 billion. Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co., thinks they'll start at a combined $12 billion and add $12 billion each quarter.

Question 3: How long will all this take?

The precise answer here lies in the answers to the questions on the caps (see Question 2), which will determine the pace of runoffs, and on the preferred long-term size of the balance sheet, which depends on how officials want to manage short-term borrowing rates (see Question 5).

Lacking those answers, it's safe only to say the whole process will take 5 to 10 years, assuming a recession doesn't come along and force the Fed to resume reinvestments, or even to buy whole new piles of bonds.

Question 4: What will the mix be in the run-down between Treasuries and MBS?

Of the $650 billion that could roll off the balance sheet in 2018 assuming no reinvestments, about $224 billion of that is in MBS, according to FTN's Schmidt. While officials haven't announced details about how they will handle the different sides of the portfolio, they have said they will look to tailor the plan to accommodate differences in the two markets.

"I would be inclined to follow a similar approach in managing the reduction of the holdings of Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), calibrated according to their particular characteristics," Fed Governor Lael Brainard said May 30.

Some analysts expect the Fed to split the caps evenly between Treasuries and MBS. Others, including Shehriyar Antia, a former policy advisor in the markets group at the New York Fed who is now chief market strategist at Macro Insight Group, think they'll go slower with MBS, a smaller market of which the Fed owns a bigger portion. His guess is that the initial cap for MBS will fall anywhere from $2 billion to $6 billion, while the Treasuries cap might be from $4 billion to $10 billion.

Question 5: How big will the balance sheet be when they're done?

Policy makers have continually stressed that, ultimately, the balance sheet may remain quite large compared to the size that prevailed before the financial crisis. One reason is that the economy has grown since then. Another is that the Fed has changed its operating framework for controlling short-term interest rates out of necessity.

Whereas the old framework hinged on keeping central bank reserve balances held by banks scarce in order to control rates, the new system allows them to set rates even as the Fed's bond purchases have bloated reserves in the banking system. Choosing between the two systems could be the difference between shrinking the balance sheet by $1 trillion and $2 trillion, according to JPMorgan's Feroli.

So far, almost all signals from the Fed are that they like the post-crisis system.

"With almost a year and a half of experience with a federal funds target above the zero lower bound, our current approach has so far proved to be both effective and resilient to structural changes in the market," New York Fed Senior Vice President Lorie Logan, the number-two officer in the reserve bank's markets group, said during a May 18 speech. "The new framework is also quite simple and efficient from an operational perspective."

Wall Street dealer banks that trade with Logan's team seem to think that is the way things are headed. In a New York Fed survey conducted in late April, the median respondent of the 23 dealers expected the balance sheet to be $3.1 trillion in size in 2025, with 22 percent of that—or $688 billion—backed by excess reserves.

Fed Governor Jerome Powell may have revealed where Fed policy makers are aiming when he said June 1 that it's "hard to see" the balance sheet shrinking to below $2.5 trillion.

To contact the authors of this story: Christopher Condon in Washington at ccondon4@bloomberg.net, Matthew Boesler in New York at mboesler1@bloomberg.net.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeanna Smialek at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net, Sarah McGregor