‘Poor Man’s Monetary Policy’ Lurks in a Low-Neutral Rate Future

‘Poor Man’s Monetary Policy’ Lurks in a Low-Neutral Rate Future

(Bloomberg) -- Central bankers don’t change their minds overnight. In the case of neutral interest rates, it took Federal Reserve officials about 1,000 days.

That’s how much time passed between the June 2016 publication of "Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants” and the March 20 Federal Open Market Committee meeting -- two pivotal moments in post-crisis central banking.

In the paper, now-New York Fed President John Williams and his co-authors concluded that neutral interest rates had fallen across advanced economies thanks to demographics, slower productivity growth and other factors. It wasn’t the first paper of its kind, but it’s an important moment to start the clock: It forcefully suggested that shared and potentially long-lasting forces were weighing down the policy setting that neither stokes nor slows growth globally.

(You’re reading Bloomberg’s weekly economic research roundup.)

Williams’ colleagues at home and abroad were open to the idea the neutral setting had declined. In America, though, officials were shy about how much of a downgrade that required of their rate-hiking cycle: Until their March gathering, Fed forecasts continued to suggest that the federal funds rate would climb north of 3 percent before coming back down.

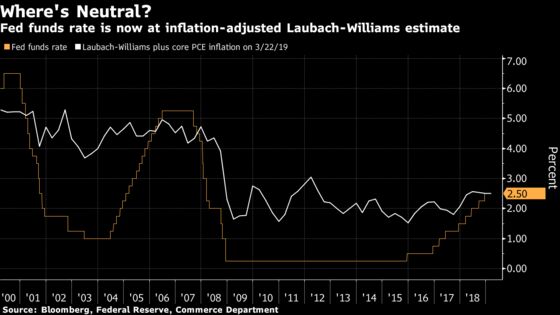

That changed last week, and officials see rates topping out the next several years at 2.6 percent. Their median estimate of the neutral rate remained at 2.8 percent, though it’s come down steadily for years.

Chairman Jerome Powell’s comments suggested that the rate setting could even stay at its current 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent target range -- roughly Williams’ current estimate of the neutral rate. The capitulation means Fed policy makers will have less room to cut rates to stimulate growth come the next recession than they’ve historically enjoyed. Their international counterparts will have even less.

Come the next downturn, officials will likely be “reduced to poor man’s monetary policy – changing the size and composition of the Fed’s balance sheet,” Citigroup’s Willem Buiter wrote in a March 19 note. The euro area and Japan may enter the next recession with still-negative rates, and neutral rates are unlikely to save the day by rising anytime soon.

“Economy-wide productivity growth is stagnant at best,” Buiter wrote. “Ageing populations boost private saving rates and weaken the incentives to invest. Fiscal dis-saving and enhanced public sector capital formation can raise the neutral real rate but are constrained, especially in the U.S., by already excessive general government deficits and a rising public debt burden.”

Other research supports the idea that neutral isn’t about to stage a rebound. Williams’ more recent work has suggested that the neutral rate will be mired at a low setting thanks to secular trends, and recent paper by Lukasz Rachel and Lawrence Summers makes the case that industrial economies could actually see negative inflation-adjusted neutral rates if they didn’t run big budget deficits.

Still, there are reasons to hope that a solution to the low-rate predicament is in the offing. The Fed is engaging in a year-long research push centered on their framework and communication, and more aggressive ideas could emerge from those efforts -- though for now, economists at Pacific Investment Management Co. LLC says the expectation is for something more "evolutionary than revolutionary." If monetary policy doesn’t get a major revamp, fiscal policy could patch the holes.

There’s a “broader paradigm shift away from discussions of fiscal austerity to a new mainstream view that fiscal policy should become a more active tool to stimulate growth,” Pimco’s Joachim Fels and Andrew Balls wrote in a recent summary of a March advisory forum. “Rising support for a more active, expansionary fiscal policy should contribute to a steeper yield curve and upside risks to future inflation.”

Also worth a read this week...

Automation -- particularly in manufacturing -- seems to be displacing workers more quickly and creating new jobs more slowly, research from The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Daron Acemoglu and Boston University’s Pascual Restrepo suggests. A slowdown in productivity in recent decades has further cut into labor demand. The point here? If future productivity growth comes from automation, “the relative standing of labor, together with the task content of production, will decline,” the authors write. Finding new tasks for laborers will be “vital for continued wage growth commensurate with productivity growth.”

Federal Reserve statisticians are combining two data sources -- the Financial Accounts of the United States and the Survey of Consumer Finance -- to produce a more real-time measure of America’s wealth distribution. The figures will be published about ten or eleven weeks after the end of each quarter, according to the paper, and "could be especially valuable during turning points or times of economic turmoil." Initial findings are consistent with what slower-moving indicators have suggested: wealth concentration has increased markedly over the past three decades. More recently, the researchers find that increased concentration continued through the third quarter of 2018 but actually decreased at the end of the year as the stock market swooned.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeanna Smialek in New York at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.