The Easy Money Era Is Over in India

The end of an easy money era is causing strain in the world’s fastest-growing economy.

(Bloomberg) -- A crisis at one of India’s biggest infrastructure financiers is the latest example of how the end of an easy money era is causing strain in the world’s fastest-growing economy.

Rising borrowing costs are putting pressure on lenders like Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services Ltd. -- whose recent debt defaults rocked financial markets in India and sparked fears of a contagion -- as well as on debt-focused mutual funds that are liquidating holdings.

There’s more pain to come as global interest rates rise and the Reserve Bank of India proceeds with its own tightening, with most economists expecting a 25 basis-points hike on Friday. The swap market is pricing in at least 100 basis points of rate hikes in the coming 12 months.

The latest turmoil comes on top of a cash crunch in the banking system and global trade tensions that are weighing on the growth outlook. These complicate the job of the central bank, which is trying to keep inflation in check amid the currency’s slump to a record low and rising oil prices.

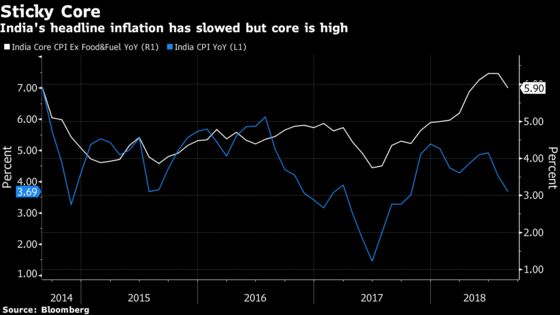

While headline inflation has slowed to 3.7 percent from a year ago, a sharp 10 percent-plus jump in crude oil prices since the last policy meeting in early August raises the risk it will imperil the RBI’s medium-term target. Core inflation, which strips out volatile food and fuel prices, has been sticky at near 6 percent.

“The MPC is facing some conflicting issues which are beyond the traditional growth-inflation trade off," said Samiran Chakraborty, chief India economist at Citigroup, who is assigning a 70 percent chance of a rate hike this week. But should the panel opt for a pause favoring financial stability, it risks a sharp knee-jerk reaction in the currency markets, he said.

The rupee dropped to a record low of 73.8188 on Thursday, taking the fall so far this year to more than 13 percent. The weak rupee along with costlier fuel and imports were cited as reasons for rising price pressures in the latest purchasing managers’ index. Overall, growth in the manufacturing and services sectors slowed, with the September Nikkei India Composite PMI coming in at 51.6 versus 51.9 in August.

The RBI has already raised rates twice since June to the highest level in two years and any further tightening will pressure borrowing costs for companies. Average yields on three-year rupee bonds of AAA-rated Indian companies have climbed 127 basis points this year, headed for the steepest yearly gain in eight, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

More Pain

For borrowers and money managers, more rate increases mean more pain.

“Interest rates will keep rising in the next two to three quarters, causing more strains in cash flow of corporate borrowers,” said Prabal Banerjee, group finance director at conglomerate Bajaj Group.

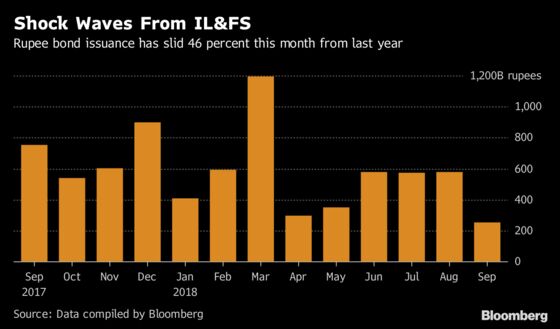

Signs of that are evident. The defaults by the “systemically important” IL&FS has raised the risk of money markets freezing up and jeopardizing economic activity. IL&FS’s defaults on commercial paper from August added to pressure on borrowing costs and led to a slump in corporate bond issuance.

All this is happening amid a hard line taken by Governor Urjit Patel toward cleaning up banks’ balance sheets. He has put founders and chief executives of private sector banks under the sword as he attempts to clean up the banking system, which has the dubious distinction of having one of the highest stressed assets ratios in the world.

Hawkish or Neutral?

With the RBI’s focus on fighting inflation, economists also see the possibility of the central bank changing its stance to hawkish from neutral.

The RBI has maintained a neutral stance since February 2017 when it switched from an ‘accommodative’ bias. Under a neutral stance, it retains flexibility where it can raise as well as cut rates depending upon how strong or weak economic data is.

“There is an outside probability of change in neutral stance, as three successive rate hikes with a neutral stance could contradict RBI’s message," said Soumya Kanti Ghosh, chief economic advisor at the State Bank of India. He expects the RBI to raise rates this week as core inflation has been sticky and the rupee has been under pressure.

--With assistance from Aashika Suresh, Anurag Joshi and Manish Modi.

To contact the reporter on this story: Anirban Nag in Mumbai at anag8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nasreen Seria at nseria@bloomberg.net, Karthikeyan Sundaram

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.