Young People Might Not Loot If They Had More at Stake

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The vast majority of the Americans pouring into the country’s streets over the past week have been peaceful protesters. Their cause -- decrying police brutality and expressing outrage over the brutal police slaying of black Minneapolis man George Floyd -- is a just one, enjoying broad support from the public. The protests have generated a sharp increase in support for the Black Lives Matter movement and a growing awareness of the racism that still plagues the U.S.

But some of the protesters turned violent, looting stores in a number of major cities and even burning down buildings. While a tiny number of those are right or left extremists intent on sparking civil unrest, much of this violent fringe probably is made up of nothing more than disaffected young people. What is driving them to tear down the cities around them?

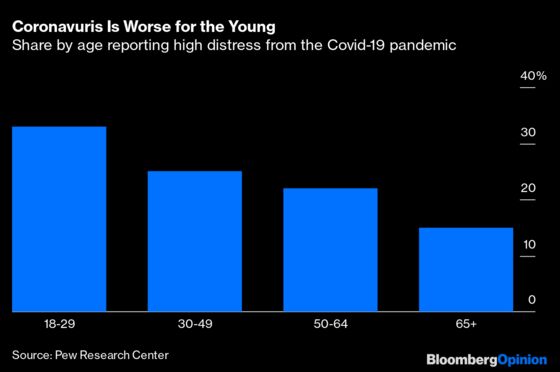

One obvious factor is the coronavirus pandemic that kept most people shut in their homes for the past 10 weeks. A combination of fear of the virus and shelter-in-place orders have wreaked havoc on the patterns of daily life since mid-March. Not only were simple pleasures like a night out at the restaurant unavailable, but constant confinement and lack of personal social interaction inflicted an emotional toll. And the grim drumbeat of rising death numbers, coupled with the fear of the virus itself, added to this isolation to create huge psychological stress. Surveys show that young people were particularly affected:

That stress had to have been a factor in turning a few young people to looting and arson.

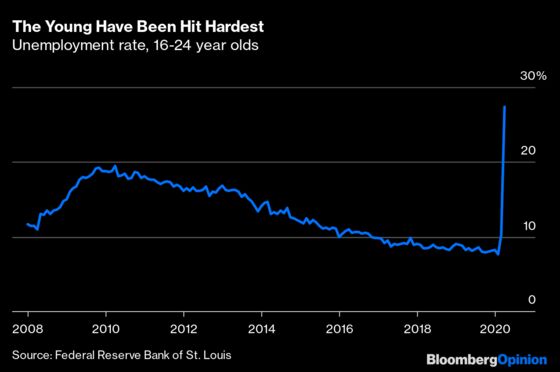

And it’s not just coronavirus and lockdowns that are threatening the youth; it’s the economic devastation they've already endured with more sure to follow. Youth unemployment is even higher than at the peak of the last recession

For now, incomes are being sustained by unemployment insurance and other government relief programs. But the loss of those jobs, and the enormous uncertainty about which industries might thrive in the post-pandemic world, means that young people’s economic future is now a fog. That is bound to generate yet more stress and frustration.

But that economic gloom comes on top of a decades-long series of economic changes that have made life harder and less certain for young Americans. As economist Raj Chetty and others have documented, a combination of rising inequality and falling growth mean young adults are less likely than ever to wind up earning more than their parents:

Downward mobility undoubtedly generates a sense of despair and helplessness among many. And income is only one way in which young people are struggling to do as well as their parents did; they’re also having more trouble building wealth.

One reason is because of the huge student loans that many young people have taken out to pay for college and have a shot at a good career. A combination of rising debt and stagnating incomes means that these loans have been taking ever longer to pay off, hanging over many people in their 20s, 30s and even 40s, tying them to jobs they don’t like, preventing them from starting their own businesses and making them fear unemployment even more.

A second reason is that many young people have been shut out of the housing market. High prices, low incomes and higher student debt have reduced rates of homeownership among the millennial generation -- a traditional escalator into middle-class wealth.

These factors have combined to make millennials the first postwar generation to be less wealthy than the prior generation. At a median age of 35, baby boomers owned 20% of the nation’s wealth; even before coronavirus struck, millennials were on track to own perhaps only 5%.

These economic factors were not the cause of the protests; police brutality was. But at least some of the young people who did turn to looting might not have done so if they had had a greater financial stake in the system. Surveys and psychological studies of looters have generally found that economic resentment plays a large role. For some young people, a gleaming storefront window represents an out-of-reach dream -- expensive goods that they can’t afford and only available to those with jobs that they can’t get. In the age of coronavirus, those jobs and consumer goods are even more out of reach.

To ensure that future episodes of protest don’t give rise to looting, the U.S. needs to have less brutal and more effective policing. But its economy and social system also needs to give young Americans more of a stake in keeping the system intact. Government subsidies can encourage companies to hire more young people and make it easier for them to buy homes and go to college cheaply. Many fewer people will risk smashing a store window if doing so would risk a job and a nest egg.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.