World Can Have Covid Boosters and Its First Doses, Too

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As the U.S. and other developed countries start rolling out Covid-19 vaccine booster shots, many are expressing concern that this will slow down the global vaccination campaign — prolonging the pandemic and causing significant harm along the way.

But there is a way to deliver boosters and speed up the next phase of vaccination at the same time. It’s the difference between pushing and pulling.

At present, vaccines are mostly purchased through what are called “pull” contracts. Manufacturers determine total production capacity, and countries simply buy — or “pull” — out of the resulting supply. That means if wealthier countries who tend to get their contracts fulfilled more promptly start rolling out boosters, then other, mostly poorer, countries have to wait longer for their first doses.

In most markets, that sort of zero-sumness is only a short-term problem. If enough buyers want to “pull” at once, then there is a strong incentive to expand capacity in order to create new supply. But a key part of the economic equation is missing for vaccines: increasing demand isn’t driving up prices enough to make investing in new capacity worthwhile for producers.

Covid-19 vaccine contract prices are usually far below market rates for good reason. Price increases would exacerbate already widespread inequality in access to vaccines, mostly along income lines. Besides, the sooner we get vaccines to everyone, the sooner we arrest the development of new variants and hopefully bring a sustained end to the pandemic. That’s the very definition of a public good.

But this means we need to think about vaccine production and purchasing differently from other goods. Instead of buying vaccines through “pull” contracts, we should be using what are called “push” contracts: orders that represent explicit commitments to purchase additional vaccine doses and to install additional production capacity to make some or all of those doses.

This strategy wouldn’t fix the problem overnight, with early booster orders cutting into existing supply. But if capacity is expanded enough through the contractual shift I’m suggesting, then total production should be able to increase sufficiently for other countries to catch up — and eventually even overtake their current vaccination pace.

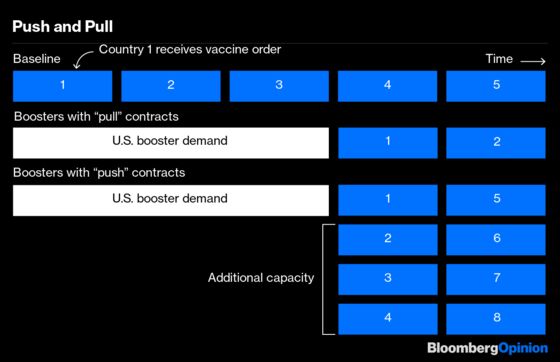

For a stylized example of how this works, let’s imagine that U.S. booster demand takes up three months’ supply of a given vaccine that would otherwise go to three smaller countries. Under the status quo, those countries just get pushed back in line by three months, and all the countries scheduled to receive vaccines after them do, as well — as illustrated in the figure below.

Now let’s imagine that the U.S. instead bought vaccines through a “push” contract with enough capacity investment to cover the full supply it had requisitioned for boosters, but the new capacity will take three months to come online. In that case, the first three countries still get pushed back in line, but they catch up right after the new capacity becomes available. And by one month after that, total production is higher than it would’ve been before, so other countries effectively move up in line.

Of course, it’s unlikely that countries would write “push” contracts that offset booster production 1-for-1 like in the example I just described. But still the same principle applies: because “push” contracts increase production throughput, they’ll eventually result in countries getting vaccines sooner than they would have otherwise.

To be sure, expanding production capacity will take more than a contractual overhaul. And the U.S. and other countries still have to do everything possible to counteract the impact of boosters on global vaccine supply in the interim. Expert medical ethicists Govind Persad, William Fiske Parker, and Ezekiel J. Emanuel recently proposed a series of strategies for this, including giving boosters at smaller dosages, and “mixing and matching” across vaccines to maximize antibody production.

All the layers of the supply chain will need to be shored up, as well. Vaccines require a range of scarce ingredients and components — everything from bioreactor bags to horseshoe crab blood — and producing vaccines at our current unforeseen scale has put strain on those inputs.

So far, more than 6 billion vaccine doses have been administered, an amazing feat in less than a year. But it’s still not enough to stop a pandemic that threatens to ravage the countries at the end of the vaccine line and spur more harmful variants. To fully address the pandemic, we have to change the way we think about buying the vaccines that are helping us beat it.

A team of colleagues and I argued for “push” contracts early-on in the pandemic for primary vaccine production. This approach is all the more appropriate for boosters because there’s less uncertainty about which vaccines we need and in what quantities.

In addition to making sure what we have isn’t wasted, there’s a role for “push”-style investment here, as well – both to raise input production capacity and to directly incentivize manufacturers to develop substitute inputs and higher-yield production methods.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Scott Duke Kominers is the MBA Class of 1960 Associate Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, and a faculty affiliate of the Harvard Department of Economics. Previously, he was a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows and the inaugural research scholar at the Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics at the University of Chicago.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.