(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The European Central Bank faces many thorny issues as it embarks on its first monetary policy strategy review in nearly two decades. From the setting of the bank’s inflation target, to its role in tackling climate change, the famed diplomatic skills of President Christine Lagarde will be tested.

One aspect of the review should prove uncontroversial, however: The ECB should do a better job of including housing costs in its definition of inflation.

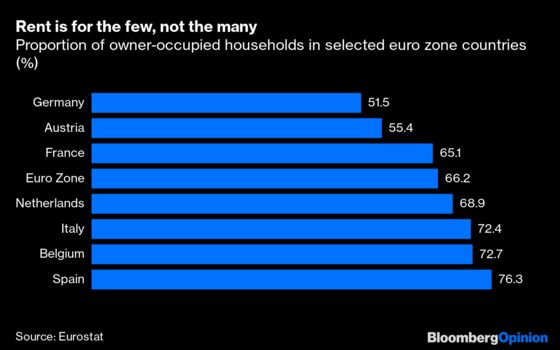

At the moment the central bank takes a very narrow view of what constitute housing costs. The “Harmonized Index of Consumers Prices” only includes rent that’s actually paid from a tenant to a landlord. This measure misses the housing costs paid by people who own their property. Since only one-third of the euro zone population is a tenant, while two-third live in a home they bought or inherited, that’s a big omission.

The ECB has said it will look closely at the issue. The review of its monetary policy strategy, which began in January, includes “the quantitative formulation of price stability,” which also means how to measure inflation. Philip Lane, the ECB’s chief economist, has been even more specific. “We at the ECB would agree that there should be more weight on housing,” he told the Financial Times this week.

The conceptual difficulty with incorporating housing costs into an inflation index is two-fold. For a start, housing is not just a form of consumption. Some people purchase a property for investment. From this point of view, housing is not different from other asset classes such as equities. The ECB’s mandate includes price stability, not boosting or containing asset prices. (Though the central bank needs to be mindful of financial stability too).

Second, measuring housing consumption is different from other goods: A consumer buys a house at a given point in time, and then enjoys the fruits of this purchase over many years. Hence, using a simple house price index would somewhat distort the picture.

The ECB should assume instead that owners pay themselves a rent over time, and impute that value. This calculation is already part of the estimation of gross domestic product across the world. It is included in the definition of inflation that other central banks, such as the U.S. Federal Reserve, use for their monetary policy.

The impact of such a change would be to lift the weight of housing in the basket of goods and services that the ECB monitors to determine inflation. At the moment this stands at 6.5%, while in the U.S. it is more than 30%. And since housing costs are rising a little more rapidly than other items, it would also increase the rate of measured annual inflation by about 0.2-0.3 percentage points, according to various estimates.

Some fear that making such a change would undermine the ECB’s credibility. The central bank is struggling to meet its target of below but close to 2%, in spite of an extraordinary set of expansionary measures. Including housing costs might bring the inflation rate closer to its target, prompting accusations that the ECB is shifting the goalposts to suit its needs.

However, there’s no excuse for bad measurement. There may be moments in the future when a spike in housing costs might make the ECB’s task of reaching its inflation target harder. And their addition shouldn’t affect the overall index that much.

Plus it’s possible that the ECB will change its inflation target to a straight 2% rate — bringing it into line with the Fed, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan. Were this to happen, you would get a balancing effect from adding the housing costs: the target would shift higher, but you’d add in some extra inflation too.

Indeed, this might make the increase in the inflation target more palatable to those who fear it would be too high. Jens Weidmann, the Bundesbank president and one of the most hawkish members of the ECB’s governing council, said this week that he wanted a “realistic and forward-looking” target, but added that it’s “unarguable” that the issue of owner-occupied housing costs needs to be addressed.

For once good economics and good politics collide. Lagarde should seize the opportunity.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.