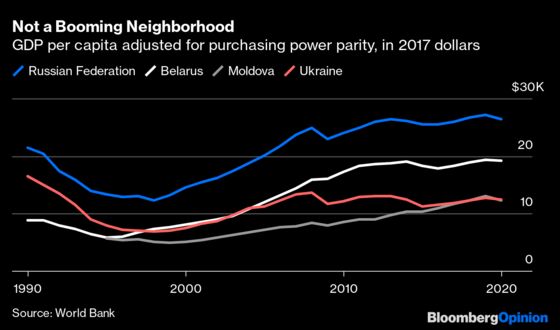

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Russian President Vladimir Putin’s motivations for invading Ukraine must have involved a mix of strategic considerations, domestic politics, historical resentments, paranoia and various other complicated matters. But there’s a simple economic backdrop that’s worth keeping in mind.

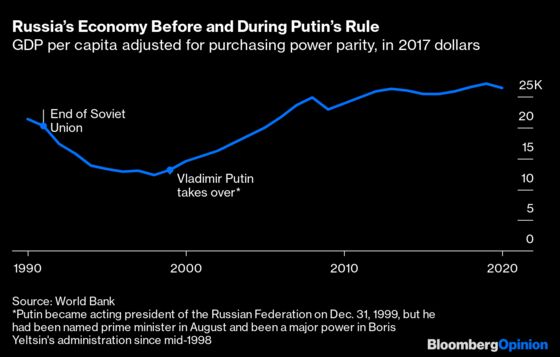

Putin took charge in Russia at the end of the extended economic disaster that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. He then presided over a strong recovery, which surely helps explain his long hold on power. Since the 2008 global financial crisis, though, Russia’s economy has stagnated.

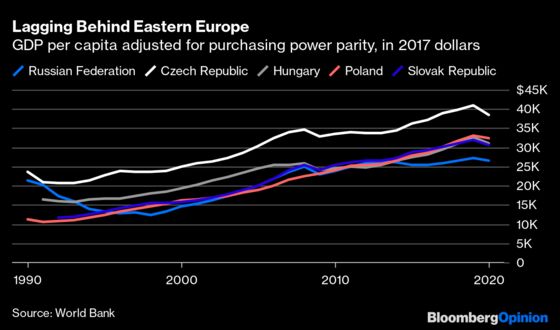

Contrast Russsia’s economic trajectory with some of the Eastern European countries that used to belong to the Soviet-dominated Warsaw Pact:

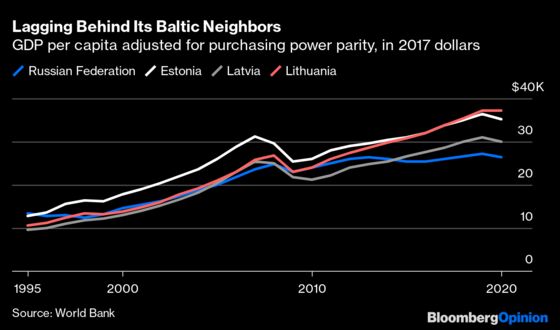

Then there’s Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, which border Russia and were once fellow members of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. All three were hit especially hard by the global financial crisis, but have rebounded strongly since.

One thing that all these former vassals of Moscow have in common is that they’re now members of the European Union. Another is that they have joined the ranks of what the World Bank deems high-income countries (the current cutoff is $12,696 in “Atlas-method” gross national income per capita, a different metric than I’ve used in the charts here). I left two other Warsaw-Pact-to-EU countries, Bulgaria and Romania, off the chart because they didn’t make the high-income cutoff (and because the chart was getting too crowded to read), although Romania is now only about $100-per-person short.

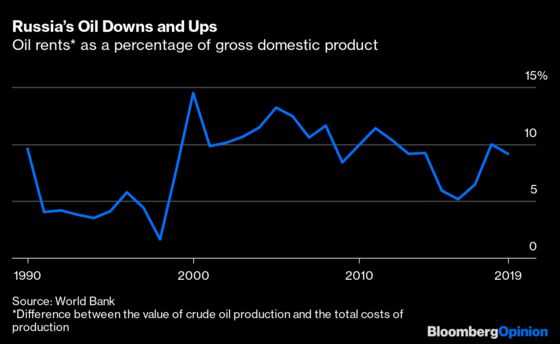

Russia, on the other hand, has remained stuck at upper-middle-income status. Why’s that? Bad Advice from American economists is often blamed for the country’s 1990s miseries, but other former Communist countries got similar advice and fared much better. A simpler explanation is that Russia is a big oil exporter, and the 1990s was a terrible time to be an oil exporter.

Oil remains central to Russia’s economic ups and downs. It’s not the only thing going on — the country’s agricultural sector has also made big strides since the 1990s, with Russia now the world’s No. 1 exporter of wheat. But despite a highly educated population and some advanced technological capabilities, the country remains dependent on natural resources and unable or unwilling to take the steps needed to make the leap to high-income or, to use the International Monetary Fund’s terminology, “advanced economy” status. Russia’s population is about one-third that of the European Union, but its gross domestic product is only one-tenth as big.

That's one of the reasons Russia doesn’t exert nearly the attractive force on neighboring countries that the European Union does. The EU has not had a great decade, weathering a long debt crisis, the departure of one of its largest members and political tensions between Western Europe and newer members Hungary and Poland. But it has delivered affluence and increased personal freedom to much of Eastern Europe, while Ukraine and its neighbors that have remain entangled with Russia have fared far less well.

It’s no wonder that many in these countries — especially Ukraine, where real incomes are lower now than in 1990 — long for closer ties to Europe. There was a time, in the early 2000s, when it seemed that even Russia was moving into the EU’s orbit. Putin and German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder were close (Schröder, despite growing outcry in his own country, remains chairman of the board of directors of Russian oil giant Rosneft). The U.S. invasion of Iraq united Russia, France and Germany in opposition. According to then European Commission President Romano Prodi, Putin asked about the possibility of Russia becoming an EU member. “I told him straight away clearly: no, you are too big,” Prodi said in 2002.

Whether or not Putin really was interested in joining the EU then, it’s clear that he has since decided that it’s a rival and a threat, probably more of one than the U.S. and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Russia isn’t competitive with the EU in terms of economic gravity or other forms of attractiveness (aka soft power), and Putin has increasingly used coercion and force to keep its near neighbors — and its own urban Europhiles — in line. Up to now the EU had chosen not to compete militarily, but the Ukraine invasion seems to have changed that. In strictly economic terms the rivalry is a huge mismatch, with Russia’s relative position likely to decline even further in the face of new sanctions. But mismatches can lead underdogs to take big risks.

More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion:

- The Quantifiable Economic Pain From Ukraine So Far: John Authers

- Ukraine Is Helping Europe Smash Some Taboos: Lionel Laurent

- Europe's Elite Reckons With Its Russian Ties: Lionel Laurent

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.