Why Private Equity Won’t Be the Savior of Fossil Fuels

It’s already hard to predict the price of commodities, and that’s before you factor in a sector in terminal decline.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There’s a frequent warning made in recent years to investors seeking to pressure companies to offload their fossil fuel assets: If listed businesses don’t own those mines, they’ll go over to the dark side.

Polluting businesses sold to private equity may continue to “operate under new owners in the shadows,” former U.S. Vice President Al Gore warned in the Financial Times last October. PE firms may be facing “the bonanza of a lifetime” if they invest in coal assets right now, Vale SA executive Luciano Siani Pires wrote in a LinkedIn post this month, saying that such businesses accounted for most of the potential “western” buyers who signed up to look at the books of its Mozambique coking coal assets.

“Precisely because coal-related assets have become toxic for listed companies, private equity firms are hunting thermal coal power plants and coal mining properties across the world at bargain prices,” Siani wrote, “aiming at juicy returns, as they do not have ESG-minded constituencies to attend to.”

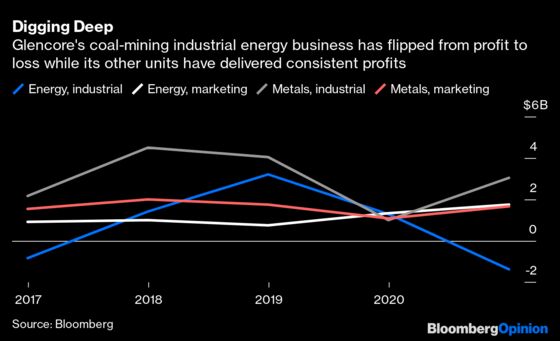

It’s hardly surprising if someone selling coal mines claims they’re a great opportunity for buyers, but there’s lots that’s superficially plausible about the theory. Since the middle of last July, the lowest price at which benchmark coal futures at Australia’s Newcastle port have changed hands has been higher than their record in any other period. Glencore Plc’s industrial energy unit — essentially a group of coal pits — will report $4.7 billion of Ebitda in 2021, the second-highest figure in the company’s history, according to Morgan Stanley estimates.

It’s also a useful bogeyman for miners wanting to keep those pesky ESG teams from their shareholders — and, increasingly, lenders — at bay. If listed companies are pushed to sell off their fossil fuel assets, perhaps there’s a sinister pile of private equity money out there that will operate them in a far more nefarious way?

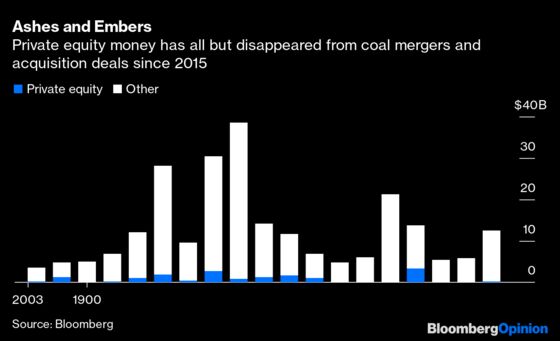

The truth is different. Far from exploding in the five years since big mining companies started selling out of thermal coal, private equity activity in the sector has very nearly ground to a halt. Of the $70 billion of coal deals since the end of 2014 for which Bloomberg has data, PE accounted for just $3.63 billion — nearly two thirds of that amount a single deal for the last of Rio Tinto Group’s coking coal mines.

The abortive second act of one of the coal industry’s most storied dealmakers is instructive. As Chief Executive Officer of Xstrata Plc in the 2000s, Mick Davis spent billions on buying cast-off pits to build the world’s largest coal export business, before selling the lot back to Glencore as part of their 2013 merger and listing. He then launched private equity firm X2 Resources to repeat the trick, as well as looking at other commodities — but despite raising $5.6 billion, the fund closed three years later without spending a cent. Davis’s current venture is looking instead at minerals “essential to the clean energy transition,” according to its website.

PE firms will always want to have a look at potential deals, but it’s not hard to see why they so rarely follow through with solid fuel. While they’d like to get a taste of the ample cashflows that coal businesses are generating right now, most of that money gets eaten up by the bank lenders who provide the leverage that fuels buyout deals.

For equity-holders and lower-ranked creditors to get their payday, firms typically need to sell the business at a decent price five-to-seven years into the future — and if it’s hard to shift coal mines right now, it’s likely to be even harder in the closing years of the 2020s.

Private equity tends to shun the resources sector precisely because it’s hard to predict the price of commodities, and consequently the resale value of a business, half a decade in advance. That’s going to be even more difficult for an industry in terminal decline.

In theory, a firm could just hold an asset beyond the usual horizon and allow it to keep throwing off cash indefinitely. It’s not implausible that the decline of fossil fuels might see the commodities often fetch higher, rather than lower prices, as we’re seeing right now. Even setting aside the need for continued funds for reinvestment, however, that’s another place where private equity is not as different from the rest of the finance industry.

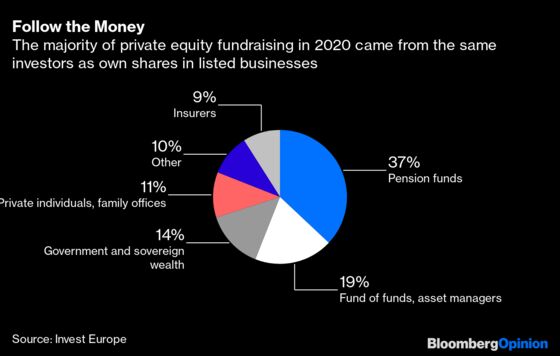

Far from having the keys to a magic money vault, PE firms raise funds from the same places as everyone else. In spite of the name, the biggest ones are all listed on public markets. More than a third of private equity cash comes from pension funds, rising to two-thirds if you include funds-of-funds, asset managers and insurers — the same constellation of investors who are putting so much pressure on listed businesses to divest their fossil fuel assets. The players who are likely to be most resistant to pressure on climate finance — family offices, private individuals and sovereign wealth funds — account for just a quarter of buyout fundraising. That won’t be enough to move the needle.

Siani’s not wrong that coal businesses might see some years of healthy income statements, even as demand for solid fuel continues to decline. That’s not enough for private equity, though, or for any business. What they need is sustainable income — not in the the ESG sense, but in the sense of earnings that are consistent, rather than flickering between profit and loss from one year to the next. The days when coal could provide that are in the past.

More From This Writer and Others at Bloomberg Opinion:

- This Coal Plan Offers Only Half a Solution: Clara Ferreira Marques

- Why Don't Europe's Oil Majors Sell Assets to Americans?: Liam Denning

- What Bill Gates Gets Wrong About Fossil Fuels: David Fickling

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.