(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Former Facebook Inc. executive Chamath Palihapitiya is very open about why he’s such a fan of special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), compared with taking a company public the usual way.

“In a traditional IPO you can’t show a [financial] forecast and you can’t talk about the future of how you want to do things, you’re just not allowed,” he said in a recent interview. He was referring to laws that exclude initial public offerings from so-called “safe harbor” protections covering forward-looking corporate statements. “Because the SPAC is a merger of companies, you’re all of a sudden allowed to talk about the future,” he told another YouTube questioner. “When you do that you have a better chance of being more fully valued.”

Unfortunately, there’s a danger that wildly optimistic financial forecasts are fueling a SPAC bubble, particularly among pre-revenue electric-vehicle companies and suppliers. The next chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Gary Gensler, should take a close look before things get really unhinged.

SPACs are listed vehicles used to acquire privately held companies and thereby take them public. The regulatory loophole that allows them to disclose forecasts to potential investors helps explain why they’re booming.

Organizers of regular IPOs tend to include only backward-looking financial information in the prospectus. This works well enough for established, profitable businesses. It’s less helpful if you’re trying to communicate the prospects of a loss-making but fast-growing tech group, not to mention companies that have yet to generate meaningful revenue such as Virgin Galactic Holdings Inc., a space-travel company Palihapitiya took public via a SPAC. The rules governing SPACs gives sponsors much greater freedom to tell their story, and they’re taking full advantage.

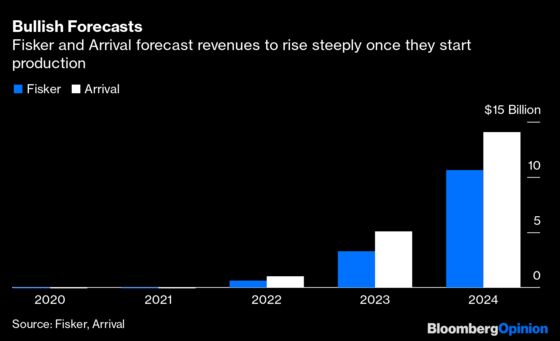

The merger presentations and statements SPACs publish once they’ve found a target typically include very bullish multiyear projections of revenue, profit and cash flow. For example, Fisker Inc. and Arrival Ltd. have yet to start selling electric vehicles. Nevertheless, each says they expect more than $10 billion in revenue by 2024. Arrival’s market value has swelled to $15.5 billion, and Fisker’s is about $4.5 billion.

The loophole is helpful, too, for companies whose revenues have declined, such as Opendoor Technologies Inc., Multiplan Corp. and Blade Urban Air Mobility Inc. Merging with a SPAC means they can more easily signpost that things will soon get better.

In fairness, this is more transparent than a traditional IPO, where business information is shared privately with Wall Street analysts and where there are quiet periods during which executives can say very little. If publishing financial projections helps reverse the trend of technology companies remaining private, which has shrunk the pool of public companies, then plenty of retail investors — who’ve been excluded from early-stage companies — would say it’s a good thing.

And yet these forecasts usually aren’t audited and, unlike in a traditional IPO, there are no underwriters affirming everything is accurate (because the SPAC is already public). SPACs do publish long warnings on why investors shouldn’t rely on such forecasts. I’m just not sure they’re always heeded.

“There can be no assurance that the projected results will be realized or that actual results will not be significantly higher or lower than projected,” reads the boilerplate warning from battery company QuantumScape Corp., which went public in November. It’s already worth $17 billion even though it doesn’t yet have a commercially viable product. “Since the financial projections cover multiple years, such information by its nature becomes less reliable with each successive year,” it added. That’s advice worth bearing in mind when considering its 2028 forecast for revenue of $6.4 billion.

At least 5 lidar technology companies are going public by merging with a SPAC. Since most will end up competing with each other for customers, their bullish projections can’t all be right, warned Kyle Vogt, cofounder of autonomous-driving business Cruise LLC, recently:

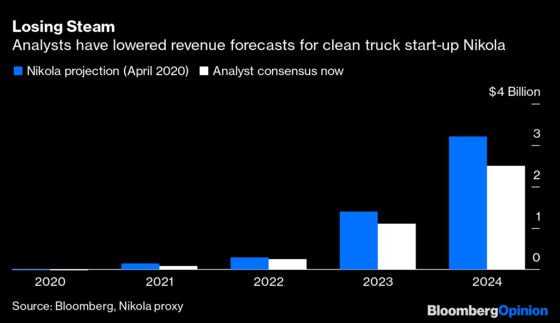

Analysts have already cut their forecasts for Nikola Corp. and Virgin Galactic, two prominent SPACs. That’s when compared with the companies’ projections published before their mergers.

Even SPACs have started criticizing rivals’ more fanciful forecasts. Emphasizing its own “conservative, risk-adjusted projections,” electric-vehicle company Proterra Inc. highlighted how competitors were anticipating much higher annual growth rates than those achieved by Tesla Inc.

Some will argue that SPAC forecasts aren’t that important because giddy retail investors don’t pay much attention to financials anyway, or they’re buying these stocks for their long-term prospects. But that underplays how these projections are used by SPACs to justify eyewatering valuations, which feature prominently in their public disclosures.

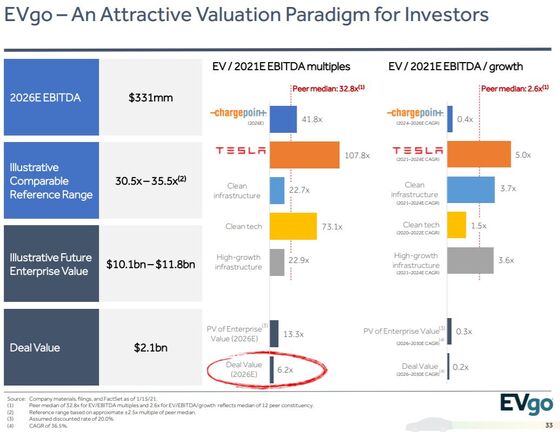

Below is a fairly typical slide, published last week by electric-vehicle charging company EVgo Services LLC when it announced a SPAC merger. It says comparable companies sell for more than 30 times a measure of this year’s earnings, so if you apply the same multiple to its projected earnings for 2026 and discount it back, you’re getting a bargain.

Who knows whether EVgo’s forecasts will prove accurate? But if you feed optimistic assumptions into such calculations, you’ll always get a very inflated valuation. Shares in the SPAC have more than doubled since listing. EVgo now has a $5.3 billion market value, more than 250 times this year’s revenue.

SPAC valuations become potentially even more warped by the companies they select as a benchmark. Canoo Inc., which plans to offer electric vehicles to consumers via subscription, chose other subscription businesses such as Netflix Inc., Spotify Technology SA and Peloton Interactive Inc. as comparable companies in its valuation analysis. That’s a pretty big stretch.

There’s certainly plenty of cause for Gensler’s SEC to intervene here. The regulator chose not to revise its disclosure rules on forward-looking statements for traditional IPOs in 2005 on the basis that companies seeking to join the stock market are “generally untested,” meaning it’s harder to assess whether their projections are reasonable.

Why should SPACs be treated differently?

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.