(Bloomberg Opinion) -- This is one of a series of interviews by Bloomberg Opinion columnists on how to solve the world’s most pressing policy challenges. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Justin Fox: You are economists who happen to be married to each other, and who started researching mortality seven years ago, just as U.S. life expectancy was about to go into decline. Your book “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism” came out in mid-March 2020, just as the pandemic was beginning to sweep across the country. So I’m a little afraid to ask, but what are you working on now?

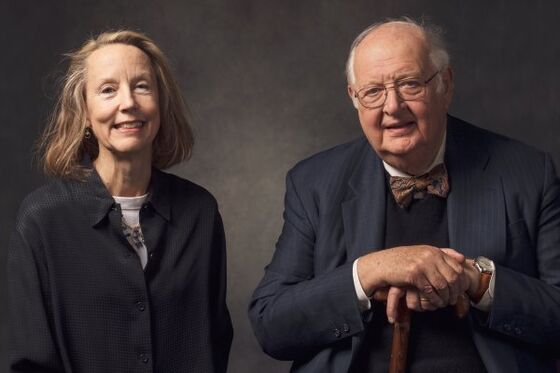

Anne Case, emeritus professor of economics and public affairs, Princeton University: We are drilling farther into suicide, which we think is the ultimate death of despair. We are moving more into the politics of despair as well. Historically, more-healthy places voted Republican, but more recently the least-healthy places are voting Republican.

Angus Deaton, emeritus professor of economics and international affairs, Princeton University, and 2015 economics Nobel laureate: Over the last few days, we’ve been looking at this announcement of 100,000 opioid deaths in 12 months. The peak monthly deaths were in May of last year, early in the pandemic. They’ve been very variable since then, but they’ve never hit that peak again, so it’s not entirely clear what’s happening.

JF: You had a paper a few weeks ago about Covid-19, and one of the things that stands out both there and in your book — and probably in what you’re finding on politics — is that the education divide is in the middle of everything. What is going on there?

AD: The U.S. has become a two-class society. We’re conferring sort of elite status on people with a bachelor’s degree and letting the rest go fish, as it were. The funny thing is that only a third of the adult population have BAs. So the two-thirds that’s not doing very well is a majority, and you might have thought that legislative politics and voting would sort this out. That’s one of the puzzles of the age, why the majority has not managed to use the political mechanism to rectify this problem.

JF: This education divide exists in political leanings outside the U.S., but does it show up across the board in other countries as well?

AC: Anywhere you look in the world, people with more education live longer lives and are healthier, for a variety of reasons. But the only other episode we could find where the life expectancy in adulthood is moving in opposite directions for people with and without a BA is in the countries of Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall. So we’re keeping very bad company.

JF: The story of how you first got into this line of research — it’s not like you had been spending your careers checking the mortality data.

AD: We were working on different things. Anne was working on pain, which is a personal issue for her, as well as an academic one. And I was working on happiness.

AC: Also a personal issue.

AD: Also a personal issue. I’ve been suspicious about whether asking people how happy they are is a substitute for collecting income and consumption data and the sort of thing we’ve traditionally done, so I thought a nice thing to do would be to compare happiness with suicide. I was working in one corner of the room on suicide and Anne was working in the other on pain. Then we discovered that not just suicide rates but a wide range of other mortality indicators were doing very badly.

AC: It’s almost like we tripped over it. That’s often the case, that you find something that you’re not looking for, and then suddenly everything changes. All-cause mortality, we found, was rising for [Americans] in mid-life after having fallen almost continually for a hundred years. We thought people must know this, but it came as a surprise to everyone talked to.

JF: My memory from back in 2015, when the first paper came out, is there was some pushback, especially from economists. There were all these supply-demand questions on the opioid epidemic: Was it because people were in despair or because the opioids had gotten so much more powerful?

AC: We think that’s kind of an Econ 101 way to think about it. We know that McKesson and Big Pharma, Purdue in particular, targeted areas where they knew demand would be high. Places where people’s mental health was failing, where people were in more pain, where people were less educated. If you’re targeting areas where you think demand is going to be high, do you want to call that supply? Or do you want to call that demand, especially for something as addictive as opioids? Vicodin has been on the market since 1978 and was one of the best-selling drugs in America. It’s slightly less strong than Oxycontin, but it is as strong as morphine and it had not created an epidemic.

AD: It’s certainly true that the pharma companies and their political enablers bear enormous blame for this epidemic. But on the other hand I don’t think you get those opioid epidemics in societies that are healthily flourishing.

JF: What was it about the environment that allowed opioids to flourish, but also led to these increases in alcohol deaths and suicides, and even maybe to some extent things like heart disease?

AC: We have to go back to the high-water mark for blue collar wages, which was 1972. After that the bottom fell out of the low-skilled labor market. Median wages among prime-aged men fell for 50 years. They went up and down a little bit with the business cycle, but the long-term trend was down. The good jobs disappeared, and people felt they couldn’t get married unless one of the partners had a good job. Home life became very unstable, and without the means to support a good life, connections to the community fell as well, including people’s affiliation with churches. Church life faltered, home life faltered, work life faltered. So that’s kind of a Durkheimian recipe for suicide right there.

JF: What is Emile Durkheim’s recipe for suicide?

AC: He predicted that times of great upheaval, positive or negative, would lead to higher suicides. What’s happened for the White working class, which happened earlier for the Black working class, is that there was an erosion of the pillars that hold life up. That gave way to people trying to soothe the beast with drugs, with alcohol, possibly with food, and ultimately with suicide.

AD: One of the questions we engage with a lot is why are you getting these things in the U.S., and not to the same extent elsewhere. Some of it is the opioid crisis. Other countries didn’t let that happen because they just regulate these things much better, and their political systems don’t depend on money so much. The distributors and manufacturers don’t have access to politicians in the way that they do here.

JF: For Americans with bachelor’s degrees, life is in many ways different — we have Zoom meetings! — but in terms of how families work it’s not a lot different from when I was growing up. For people without bachelor’s degrees, you look at the numbers you have in your book and it’s pretty amazing how different it is.

AC: We see this move from marriage to cohabitation. In Europe cohabitations tend to be more stable and in the U.S. more brittle. So we have a kid together, we break up, we re-partner, we each might have another kid, but there’s no sort of stability that someone getting to midlife can look at their family and feel that they’ve had both pleasure and solace out of being home.

AD: What happens if you get to be a 55-year-old guy and you’ve had maybe one or two sets of children, but you don’t know them, they’re living with other men, with your ex partners? When I think of how important family is to our families, and how so much of the goodness in our life is centered around that, the fact that this has been taken away or it’s gone away....

AC: One of the things really came up in our research was the arrival of the pill. For many, many, many women, that was just a wonder that they could control their fertility, they could continue their education, they could start careers and it was all good. But for women who weren’t college-bound, they lost negotiation power over sex. The sexual mores changed so that they were left without having the stability of a home life with a husband that they might have had one generation earlier.

AD: The changing of the social institution of marriage, which conservatives have emphasized, and they’re right, has really favored one class of women against the other.

JF: Conservatives have also emphasized that maybe there’s a changing attitude about work, that people don’t have the same work ethic.

AC: What we were able to document is both falling wages and lower labor force participation. If both of those things are falling at the same time, it suggests a shift down in the demand curve for low-skilled workers. Otherwise, if more and more workers left the labor force that should push wages higher. So it’s kind of hard on face value to say this is just this lack of industriousness among working-class people.

JF: This is a case where Econ 101 does seem to have the answers.

AD: Yes! It really does help.

AC: One thing that hasn’t come up so far is the role that the health care industry plays in the low-skilled labor market. We tie people’s health insurance to their employment in a way almost no other rich country does. As health care costs have skyrocketed, employers look at a low-skilled worker and think, I really don’t want to pay my share on a $20,000-a-year policy for a working-class family, because this worker is just not worth that plus what I have to pay him or her in wages. We think the healthcare industry has a lot to answer for as well here in terms of destruction of good jobs for less-skilled people.

JF: Just to understand that a little better, the argument is that because we’ve attached health care provision to employment, it leads to a whole bunch of behaviors that kind of hammer working-class America on the head?

AC: It used to be, I was a proud worker in a hotel chain and maybe if I was good at what I did, I moved up. Now I work for a cleaning company and there’s no ladder up. I’m just doing this work with few benefits. If I get sick, I’m out.

AD: If you think of a $10,000 a year policy, which is for a single person, if that person works 2,000 hours a year, it’s an extra five bucks an hour on the wage. Think of all the fuss around the minimum wage. People don’t talk about this to the same extent, but it’s a horrible drain. It’s like tying dead weight to the less-skilled labor market.

JF: Without some sort of system where low-wage workers are in the same pool as all the rest of us, and some sort of cost control, it seems like this continues, right?

AD: Exactly right. You need cost control, and you need automatic enrollment. You get this conservative position that any price control is going to bring the end of the world. Well, we’re getting the end of the world without price control, because we get this unholy melange of markets and politicians in a way that’s just ripe for cronyism and taking money from the poor and distributing it up.

JF: So healthcare is the big thing. What else would have to change to not have this continue?

AD: We’ve got to rebalance power between capital and labor. That permeates lots of things like the courts, which have become much more pro-business, and the access to politics in which the only voice that many working-class people have is a sort of protest voice.

AC: In addition to that, I think there have to be changes in our K-12 education system. In many places, high schools are focused on the minority of students who are going to college, and everyone else is more or less on their own, goodbye and good luck.

AD: There’s got to be a route to dignified, socially recognized work other than college. I mean, college is not like a vaccine that protects your health. It’s a key into a part of society that’s a much better place to live.

AC: It’s also that there are jobs where someone really does not need a college degree, but given the number of applicants that come in over the web now, in the tens of thousands for a job, it’s a screen. If we could make employers more aware that they may actually find better workers among people with a high school diploma, that might be something to shoot for.

JF: How hopeful are you of any of these things actually happening?

AD: Not very. The forces that we’re writing about are incredibly powerful everywhere. It’s not just a matter of Republicans. Lots of Democrats live in areas where pharmaceutical companies are really important. There’s a hospital in every congressional district.

AC: I guess if I was going to be hopeful, it would be that a lot of these problems need to be solved at the community level. There are differences of opinion on this, but it looks like the crack epidemic ended because the communities got their hands around it. In terms of bringing people back and giving them more connection, it’s not as if we could bring a solution from on high anyway. A lot of these are going to have to be dealt with at that level.

AD: The last time around, in the Gilded Age at the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century, there were four amendments to the Constitution, and those were all led by popular movements. They were led from below. The amendments that allowed women to vote and instituted Prohibition were led by women. The introduction of the income tax was a great protest against inequality — we might have to do that all over again for a wealth tax. The direct election of senators was a protest against corrupt state governments. You could think of parallels for all of these things here now.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.