(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s the central battleground in the conflict over just how much home-working should continue if life eventually normalizes: the grimness of commuting. For years, the assumption has been that commuters were responsible for their lot — and longer and more expensive commutes were implicitly covered by their salaries. That old certainty is now in doubt.

The popularity of WFH is highest among those who commute. Avoiding this journey “of some distance,” as the dictionary defines it, was the most commonly cited reason in support of WFH in a survey by pollster YouGov for the U.K. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development conducted in December and January. Among office workers who prefer to WFH most or all days, 62% said their commute was too long, according to a more recent YouGov poll for real-estate analytics firm Locatee.

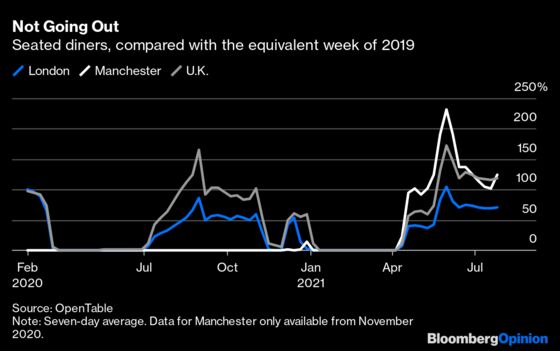

These dynamics will contribute to a slower return to office life in cities where commutes are longer, even before layering on worries about Covid infection, with implications for city economies and commercial real-estate valuations. London respondents in the Locatee survey were more likely to say their commute was too long and too expensive. Is it any wonder then that London has bounced back less rapidly than the rest of Britain?

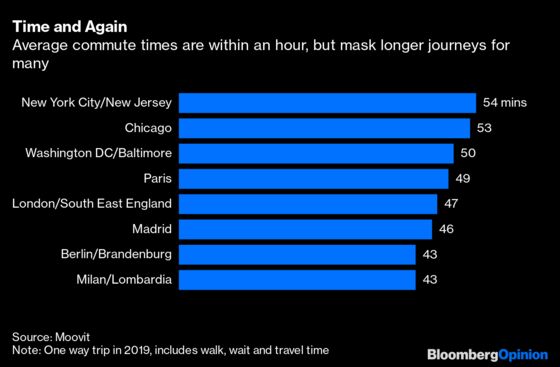

In 2019, the average one-way commute in London and the southeast of England was 45 minutes, with 18% of commuters enduring a trip of between one and two hours, according to Moovit, a subsidiary of Intel Corp. For New York and New Jersey, the average commute was 54 minutes, with 27% commuting for one to two hours. This includes walk, wait and travel times.

Even though commuting absorbs so much time and energy, there’s a lack of academic work comparing it across global cities. It can’t help that commuters don’t cut a sympathetic figure. They live in the suburbs or the sticks, and tend to be older. They have a “season ticket.” Those very words express disenchantment. They have seemingly chosen the bland metric of price-per-square-foot over urban bohemianism.

It’s also incredibly hard to measure precisely the negative value of the commute. The financial cost of public transport or fuel and parking is one component. The quality of the journey itself matters just as much.

A commute may involve standing in a crowded suburban service that takes 40-50 minutes to reach a central terminus, stopping every few minutes as new passengers barge on demanding that those inside move down into the carriage. People who live further out can often get express services. Getting on at the start, they find a seat. The train takes an uninterrupted course through pretty fields and towns. Passengers convince themselves they’re “decompressing” on the way home. But a season ticket for these usually longer-distance services will be fiendishly expensive.

We have to fall back on the body of studies putting a value on time given up to various modes of transport, or waiting for buses. And however the journey is done, it feels like work to varying degrees.

“Based on the value of the time that people assign to it, [the data suggest] they dislike commuting as much as being at work, a bit less for commute by car and more, if not a lot more, for some transit commutes which are slow, crowded, and unreliable,” says Gilles Duranton, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

Could this time and cost not be released for the benefit of both worker and employer, especially in cities like London, New York and Paris where people spend so much time on public transport? This happened naturally to some extent in the pandemic. A recent study by academics José María Barrero, Nick Bloom and Steven J. Davis found that around 35% of time saved commuting was put back into the employee’s primary job.

Workers clearly feel emboldened to make a stand against losing something they see as valuable in WFH. The Locatee survey found that Londoners wanted 5,100 pounds ($7,128) to return to the office full time (as it happens, around the higher end of season ticket costs.) It’s one thing to want to hold onto the savings from ditching the season during the pandemic, but quite another to demand a full-blown raise for working the same way you did in 2019. A separate study by Barrero et al found that 40% of U.S. workers would start looking for another job if forced to return to the office full-time.

But for employers, this cannot be a purely financial negotiation. It’s a strategic matter. As Bloom says, organizations that go full WFH risk becoming less innovative and losing cultural cohesion — downsides that take time to become apparent. A commuting workforce can be seen as necessary for long-term corporate success.

Of course, these dynamics are encouraging the compromise model of a few days in the office and a few remote (although it’s a nightmare deciding precisely which), or flexible hours to dodge the morning or evening rush. Bloom says that people value the hybrid style like it’s a 7%-8% pay-rise. Whether employers want or need to pay the same uplift to enforce pre-pandemic working will depend on the job market. The bottom line is that firms fighting over talent can't individually control the cost of hiring someone when they face competition.

Younger workers may not be celebrating commuter bargaining power right now. Living more centrally, they’re the ones in the surveys who aren’t cheering WFH. But however determined they are to resist drab suburban life, many will benefit when they inevitably become the commuters of tomorrow.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Hughes is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals. He previously worked for Reuters Breakingviews, as well as the Financial Times and the Independent newspaper.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.