(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Europeans are the heaviest drinkers in the world, according to a new World Health Organization report. Alcohol killed 291,000 people in 30 European countries in 2016, more than 10 times the number of deaths caused by traffic accidents in the European Union that year. The U.S. opioid epidemic only kills about a quarter as many people every year.

But consumption and mortality levels don’t tell the whole story. The WHO report sheds light on how alcohol problems can be mitigated with smart policies that drive cultural change.

Alcohol consumption levels in Europe as a whole didn’t change between 2010 and 2016, the latest year for which full data are available. The average adult European drinks 11.3 liters of pure alcohol a year, compared with 9.8 liters in the U.S.; that’s some 425 grams of 80 proof hard liquor per week. What the organization’s experts call “heavy episodic consumption” has become less prevalent – only about 30% of adults drink the equivalent of 150 grams or more of hard liquor at least once a month, compared with 34% in 2010. But the decrease has stalled now. As a result, alcohol caused 5.5% of all deaths in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland, higher than the global average of 5.3%.

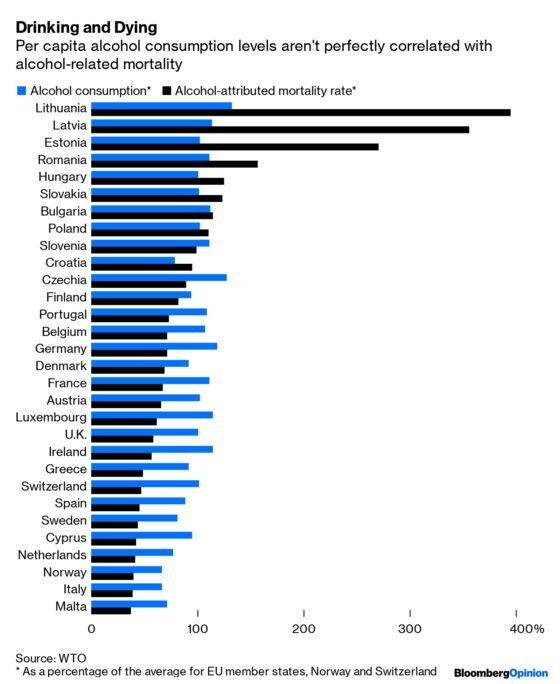

That’s quite an alcohol problem, but only for parts of Europe. For example, the alcohol-related death rate in Lithuania is 10 times as high as in Italy, even though the Baltic nation’s consumption level is only twice as high.

The correlation between alcohol consumption and mortality is only 0.49, so Lithuania’s higher death rate seems out of whack. One obvious explanation for the disparity is that health care systems in poorer countries aren’t as good at treating the effects of alcohol consumption as in wealthier ones. Besides, life is grimmer for the poor in the less affluent nations. It not only drives them to drink but the quality of the alcohol they consume is lower, resulting in more deaths. The WHO report shows that in Greece between 2010 and 2016, the per capita consumption of legally-produced alcohol dropped by more than two liters a year, but the decrease was almost exactly offset by a jump in illegal booze. As a consequence, Greece was one of only the seven European nations where alcohol mortality increased over that period.

In post-Communist countries, other explanations for heavy and disproportionately harmful drinking include higher levels of inequality and the stress of the transition to capitalism.

WHO recommends governments introduce restrictive alcohol legislation and measures to increase public awareness of the harmful effects of too much consumption. In practice, though, those efforts don’t quite work as intended. High alcohol taxes are an especially blunt instrument: They tend to be regressive, hurting poor people more. The result isn’t that people drink less but that they get even poorer and switch to more harmful home brews, like in Greece. In the Baltics in particular, uncoordinated attempts to raise alcohol prices through taxes have resulted in large numbers of people crossing borders to buy booze or get drunk. According to the WHO report, Estonia, with its high alcohol duties, has managed to reduce drinking by tourists (who had been coming from Finland) but its own citizens have started traveling to Latvia for their liquor.

Lithuania has some of the EU’s toughest alcohol laws, which have become politically unpopular. The country has raised the legal drinking age to 20, restricted selling hours and raised taxes. But it still holds the European record for both consumption and alcohol-attributed mortality. That means something is likely wrong with the way the policies are calibrated.

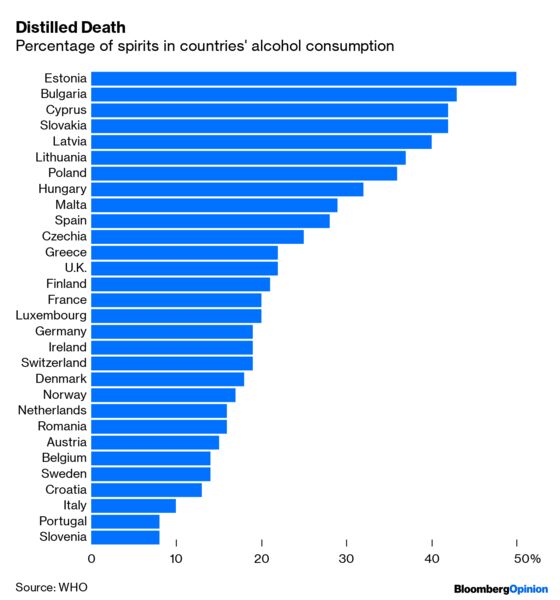

WHO data show show that one factor better explains alcohol mortality in Europe than relative wealth or even relative consumption. It’s the share of spirits in overall consumption. Generally, the more hard liquor a country drinks, the more people will die from alcohol-related diseases – cirrhosis of the liver, heart conditions, specific forms of cancer – and accidents. The correlation between the share of spirits and mortality is 0.54.

A smart alcohol policy should be aimed at shifting the mix away from spirits. The Netherlands and the Nordic countries, traditionally fond of hard drink, have cut down their share in consumption by not selling spirits in supermarkets. Governments should be setting lower taxes and age limits for weaker drinks, like wine and beer, than hard liquor to make them more attractive.

There’s nothing much Europe can do about alcohol’s ubiquity: more than 70% of adults drink it, a level never reached by any other addictive substance, including tobacco. But countries not blessed with the consumption habits of wine-loving Italy or beer-obsessed Belgium can at least try to push people toward drinks with a lower alcohol content.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stephanie Baker at stebaker@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.