(Bloomberg Opinion) -- I’ll be cooking duck for Thanksgiving this year. That’s partly because we’re having too small a crowd for a whole turkey, but also because duck is great (here’s a hard-to-mess-up recipe). I know exactly where our duck will be coming from — a farm in Ferndale, New York. But as I contemplated our meal plans recently, my thoughts drifted to a for-me inevitable place: I bet the U.S. Department of Agriculture has data on duck production by state. Wonder where they raise the most ducks?

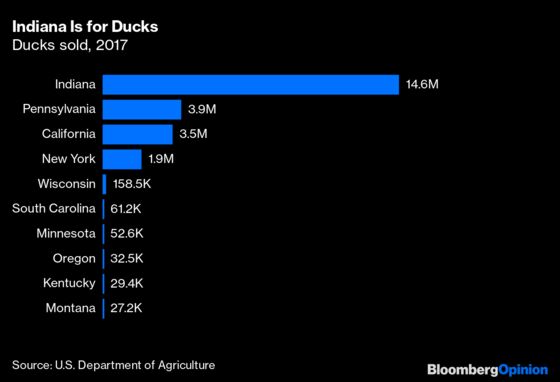

It’s Indiana, by a mile. The state’s 14.6 million ducks sold in 2017 came mainly from one producer, family-owned Maple Leaf Farms — “the first Duck Dynasty,” as a family member once put it. It’s located in Leesburg, about midway between South Bend and Fort Wayne, although it contracts out much of the actual duck-raising to nearby farmers. It also has a sister company, Down Inc., a down and feather bedding manufacturer. A lot of U.S. duck meat is exported to Asia, but Maple Leaf’s is chiefly for domestic consumption, although it now has breeding operations in China too. Oh, and the numbers here are a few years old because the most recent state data I could find were from the U.S. Census of Agriculture, which is conducted every five years.

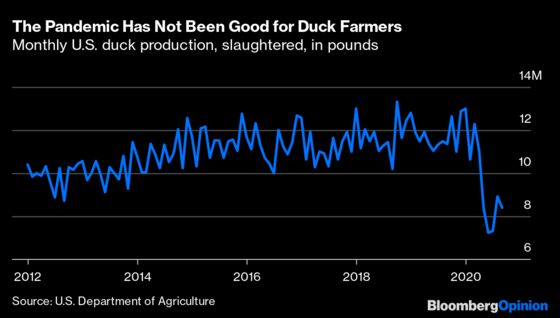

There are more recent national production numbers, though, and they’re not looking great for the duck business. A large share of U.S. duck consumption occurs in restaurants, usually pretty fancy restaurants. And this has of course been an awful year for fancy restaurants.

So that’s one more reason to consider serving duck at Thanksgiving. The nation’s duck farmers need you!

I know, I know, you probably won’t serve duck. You may be curious, though, where the things you do plan to eat on Thursday come from. And while you could just go look it all up on the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service’s Quick Stats site, you’d surely rather just keep reading while I show you which states produce the most of some key Thanksgiving meal ingredients. Right?

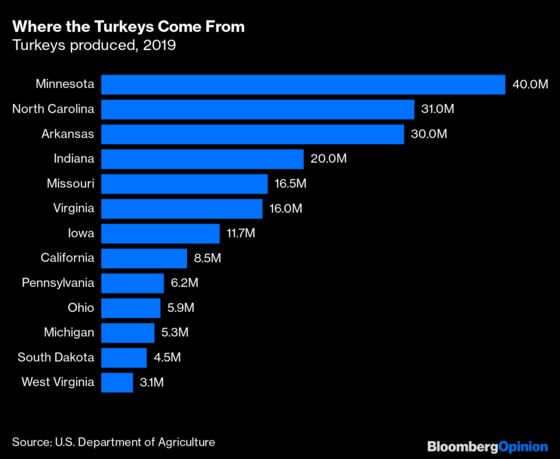

To start, turkey:

These are all the states for which the USDA regularly releases production data, but another 30.3 million turkeys came from other states in 2019. Turkey production is quite widely distributed around the country, which is somehow comforting.

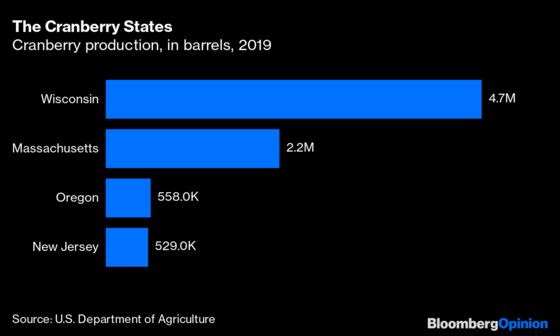

It’s a very different story with cranberries, which are grown commercially in only four states.

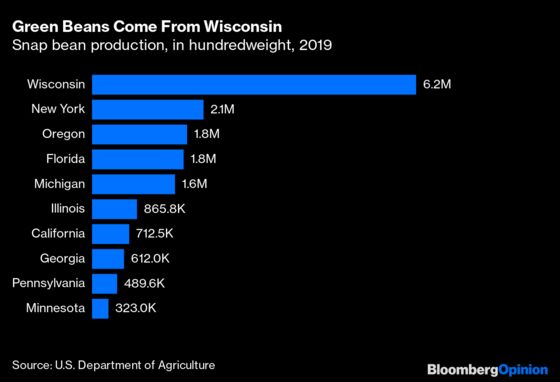

A barrel of cranberries is simply 100 pounds of cranberries. I thought about converting that to pounds, but barrels is how the USDA reports it, and it seemed more charming and no less informative just to leave as is. Same goes for hundredweight, which in some contexts can mean more than 100 pounds but in USDA reporting appears to be just that. It’s what snap-bean production is measured in.

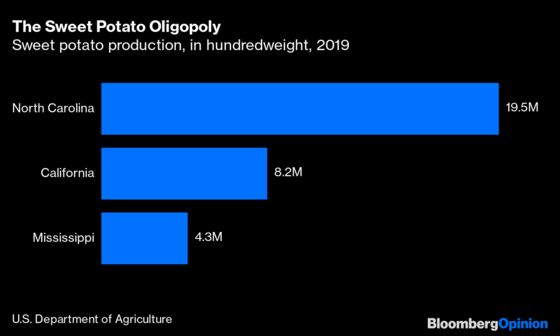

Wisconsin’s dominance in two key Thanksgiving side dishes was not something I expected. The general rule is that if it’s a crop people eat, the No. 1 producer will most likely be California, while if it’s something cattle or hogs or chickens or turkeys eat (corn and soybeans, basically), it will be Illinois or Iowa. Thanksgiving food seems to break most of those rules, though. Here’s sweet potatoes, also measured in hundredweight.

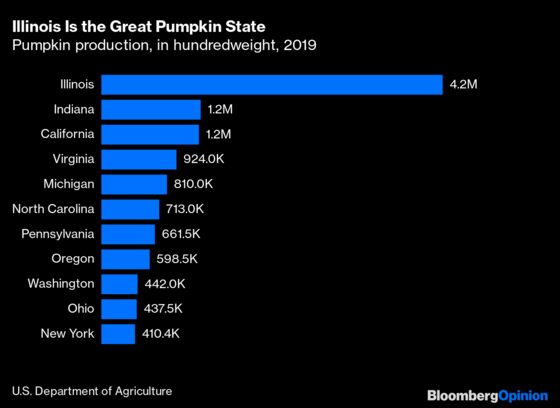

I know for a fact that sweet potatoes are grown in other states, since I buy them at my local farmers market in New York. But those are the only three states that grow enough for the USDA to bother keeping track. Pumpkins, meanwhile, are grown commercially pretty much everywhere, but Illinois is the No. 1 producer by a lot.

Libby’s, the canned-pumpkin market leader, has its roots in Chicago (although its parent company is currently based in Switzerland), which helps explain why Illinois is on top. After bad weather there led to a canned-pumpkin shortage at Thanksgiving in 2009, the industry does seem to have diversified away from the state somewhat. In 2008 Illinois accounted for 47% of U.S. pumpkin production; last year its share was down to 31%.

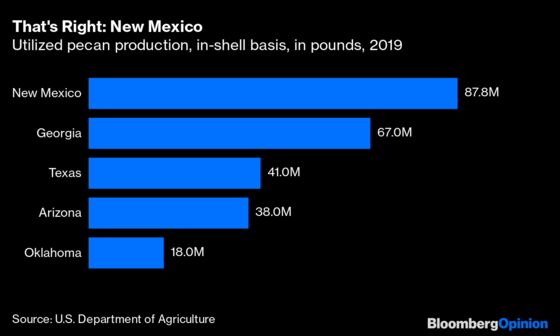

As for that other key Thanksgiving pie ingredient, pecans, the leader may surprise you.

New Mexico passed Georgia in pecan production in 2018. And while there used to be enough pecans grown in Alabama, California and Louisiana for the USDA to pay heed, it stopped tracking their production last year. The Southwest, broadly defined, has become the new pecan heartland.

There are other Thanksgiving ingredients I could make charts of, such as apples (Washington is No. 1) and potatoes (Idaho, duh). But there are limits, and you may need to get started on that pie anyway.

Here’s a final takeaway: Agricultural writer Tom Philpott has a new book, “Perilous Bounty: The Looming Collapse of American Farming and How We Can Prevent It,” in which (if I understand correctly; I haven’t read it yet, but I will) he argues that irrigation-intensive agriculture in dry California and the corn-soybean-and-livestock complex that dominates farming in the heartland are both unsustainable. He may be right! But as the charts here show, there is some geographical diversity and surprise left in American farming. Which is something to be thankful for.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.