(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In September 2004, the linguist and philosopher George Lakoff published a slim volume that became a surprise bestseller in progressive circles after Senator John Kerry somehow managed to lose the presidential contest to unpopular incumbent George W. Bush. Lakoff’s book “Don’t Think of an Elephant!” provided intellectual comfort food to liberals who couldn’t understand why left-of-center policies that poll well never seem to win at the ballot box.

His explanation centered on language. By using terms like “death tax” and “partial-birth abortion,” he argued, conservatives managed to control the debate over once-obscure concepts (e.g., one form of capital gains tax, a vanishingly rare medical procedure).

One of the surest signs that people on the left paid attention is the way in which their candidates now talk about child care. Nearly all the Democratic presidential candidates this year tout some form of “universal pre-K” or “early childhood education.” What you won’t hear them call it is “day care.”

Democrats used to talk about “affordable child care” and “universal day care” quite a bit. But during the late-20th-century culture wars, conservatives opposed to increased government spending and anxious about women working outside the home conjured up images of cold, selfish career women warehousing their children in Soviet-inspired, government-run facilities. Viable proposals for universal day care essentially died the day President Richard Nixon vetoed the Comprehensive Child Development Bill of 1972, citing “family-weakening implications.”

It’s true that many on the left, especially those in the “women’s liberation” movement, continued to argue for free or more-affordable day care, pointing out that the dual-earner family had become the norm. But the U.S. has always been deeply ambivalent about “liberating” women to work. Even today, only 18% of Americans think it’s ideal for both parents to work full time, while 44% say it’s ideal if one parent gives up outside work (in opposite-sex couples, this is usually the woman).

So now, perhaps taking a cue from Lakoff, Democrats talk about “pre-K” rather than day care, and extol the long-term benefits of early education not on working women’s careers, but on children’s brains. And this approach seems to be working.

When polling questions on this issue are framed as an investment in children’s learning, support is quite positive. A 2014 Gallup poll showed that 70% of Americans favored “using federal money to increase funding to make sure high-quality preschool programs are available for every child in America.” This was significantly higher than a 2016 Gallup poll that asked the question in a slightly different way — a question about whether to “enact free universal child care and pre-kindergarden programs for all children” got only 59% support. (In the 2016 poll, 16% also said they had “no opinion,” which wasn’t an option in the earlier survey, and contributes to the different results.)

Polls by advocacy groups that emphasize access to “high quality preschool programs” and “better early childhood education” also tend to find bipartisan support, while those that tout “child care” are much less popular with Republicans. In 2016, the First Five Years Fund found that majorities of both Clinton and Trump voters would support “making available high-quality early learning programs for infants and toddlers to give them a strong start on developing school-ready knowledge and social skills.” Knowledge and skills? Who could be against them? In contrast, the 2016 Gallup poll that spoke of “child care” found only 36% of Republicans in support.

I don’t mean to pooh-pooh the value of early education for children; it is real. I just want to point out that mothers also benefit. In fact, several recent studies have suggested that offering early-childhood care could help more than any other policy to address the motherhood penalty, one of the biggest contributors to the gender pay gap, and boost women’s labor-force participation. In the two years after public preschool was introduced in Washington, D.C., for instance, mothers’ workforce participation jumped 12 percentage points, and researchers estimated that 10 of those points were attributable to the new policy. The increase was highest among low-earning women, but high-earning women also returned to work in significant numbers.

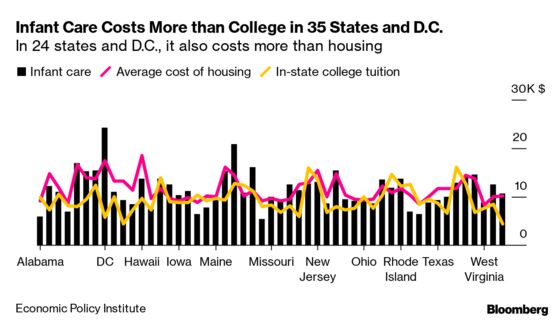

Similar studies in other countries saw jumps of 5-10 percentage points. The impact may be stronger in the U.S. because the cost of early childhood care here is staggering (especially in Washington, D.C.). In 35 states and the District of Columbia, infant care costs more than in-state college tuition, according to the Economic Policy Institute. In 24 states and D.C., it costs more than housing.

When faced with the cost of child care, opposite-sex couples sometimes default to questioning the value of the woman’s salary. As one husband recounted to researcher Erin Reid: “I said to her, ‘If you take your job and net out all of the day care expenses and net out all of the extra tax that we have to pay because you work, we’d fundamentally be making the same amount of money between us.’” But such calculations almost never include the economic penalties women pay for taking time out of the workforce. Given the fact that women choose to work longer hours when they have access to affordable care, women seem to prefer to work.

As presidential candidates wrestle with whether to provide public pre-K or means-tested programs for children, they should keep in mind that while such programs disproportionately benefit low-income children, they also help women at all levels. And when women do better, families and the economy do better, too. So fine, keep calling it pre-K.

Workforce participation rates among middle-class mothers didn’t change as much, probably because so many were already working – it’s hard to support a middle-class family in America without two incomes.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mary Duenwald at mduenwald@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Sarah Green Carmichael is an editor with Bloomberg Opinion. She was previously managing editor of ideas and commentary at Barron’s, and an executive editor at Harvard Business Review, where she hosted the HBR Ideacast.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.