What Walmart Can Learn From a Failed British Banking Experiment

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In spring 2009, as the world reeled from the financial crisis, Terry Leahy, then chief executive officer of Tesco Plc, set out a bold ambition: to transform Britain’s biggest retailer into the “People’s Bank.”

With many lenders’ reputations tarnished, Tesco and rival J Sainsbury Plc spotted an opportunity to capitalize on the trust in their grocery brands and capture a slice of the U.K. banking market. But the two overshot. Fast forward a decade, and Tesco has retrenched from offering mortgages and current accounts. Sainsbury is considering a sale of its bank.

Now Walmart Inc. has its own lofty financial services ambitions. The world’s biggest retailer recently formed a fintech startup in the U.S. and hired the head of Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s consumer bank to lead it. Its timing may be better than that of the British chains, with financial regulators less worried about fragility in the system and new technology making it easier to offer services outside of traditional banks. Even so, if it’s serious about building a “Bank of Walmart,” the company will need to avoid making the same mistakes.

Tesco and Sainsbury first added products like credit cards, loans and insurance in the 1990s after striking joint ventures with banks. These efforts trundled along for a decade or so until the 2008 crisis, after which the grocers took full control of their financial businesses. This is when things got tricky.

The retailers underestimated the complexity of building a banking arm and the scale needed to compete with incumbents. Going it alone meant investing in all their own systems. Distracted by this and other ambitions (Tesco wanted to expand globally), they lost sight of their core grocery markets at a crucial time — when consumers (and sales) were migrating to the web and low-cost competitors were stealing market share. Meanwhile, U.K. regulators were stepping up their oversight of banks and increasing capital requirements, making financial services even more burdensome.

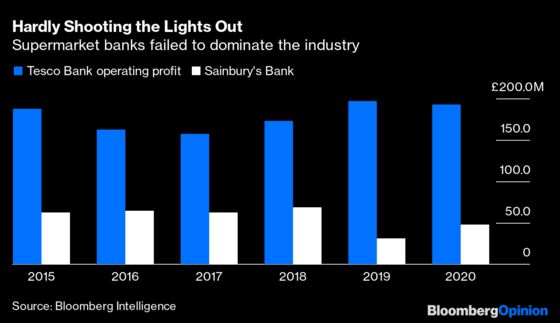

Each supermarket has probably invested up to 1 billion pounds ($1.4 billion) in creating a freestanding bank. Yet Sainsbury’s makes an annual operating profit in the range of tens of millions of pounds. Tesco makes more from financial services — between 150 million and 200 million pounds a year, excluding one-off charges — but it’s hardly the dominance that Leahy had in mind.

Walmart has perhaps learned from their experiences. Rather than go it alone, the big-box giant formed its new fintech company with venture capital firm Ribbit Capital. It has also said it expects the startup’s growth “may come through partnerships and acquisitions.”

Although Walmart has offered few details about its ambitions, the breadcrumbs it has dropped suggest there won’t be a big push to open physical bank branches. A spokesperson told Bloomberg News that the company is not planning to seek ILC status, which would allow it to offer services including accepting deposits and making loans.

Instead, Brett Biggs, Walmart’s chief financial officer, said recently that the venture is an opportunity for something “more sophisticated, more digital” than its current offerings, which include check cashing and money transfers. Here, Ribbit’s involvement is telling, as the investment firm has backed fintech disruptors such as Affirm Holdings Inc., which offers the “buy now, pay later” format that has become ubiquitous on online shopping sites.

Walmart will have to work hard to avoid the British supermarkets’ biggest misstep: getting distracted from new competitors entering their core retail business. In the years after the financial crisis, the cash-strapped middle-classes turned to the no-frills German grocers Aldi and Lidl that had expanded across Europe.

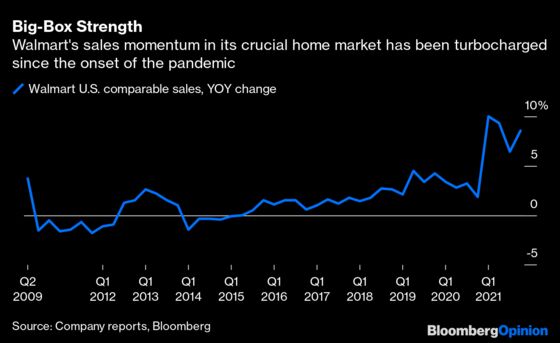

The risk of distraction is even higher for Walmart, given that it’s in the throes of transforming its primary business to compete against Amazon Inc. This year it is plowing billions of dollars into efforts such as opening more microfulfillment centers — areas in its stores where robots help workers assemble online grocery orders. It is also looking to bolster its Walmart Connect advertising business, which it hopes will become a significant revenue stream.

This is a lot to manage on top of launching a fintech startup, though it should help that this entity will be a separate company. And Walmart’s core U.S. grocery business is firing on all cylinders.

Walmart should also take heed of what the U.K. supermarket banks did right: They were brilliant at leveraging the customer data tied to their loyalty programs. Tesco’s Clubcard, for example, has 20 million members. As long as customers give the supermarket permission to use their information, it knows what they buy, whether they visit the same store every week and how much they spend — pretty useful intelligence for determining how reliable they will be in making loan repayments or how far they drive to price car insurance.

Walmart doesn’t have a traditional loyalty program, but it has a vast storehouse of data about how customers behave in supermarkets and online. Its new Walmart+ membership, which includes free grocery delivery and other perks, should add to its trove. The company should harness that data to figure out which fintech products make most sense for its customers.

Even with their data advantage, British supermarkets failed to upend the banking industry. This underlines just how challenging it will be to stop the “Bank of Walmart” going the same way as Tesco’s “People’s Bank.”

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

Sarah Halzack is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She was previously a national retail reporter for the Washington Post.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.