(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For those awaiting more aggressive action on climate change, it may look like a breaking point has finally arrived.

A sudden collapse in fossil-fuel markets akin to the 2008 financial crisis has long been a scenario for how the world switches to a less carbon-intensive path. With Brent crude trading below $35 and the average yield on the U.S. energy sector’s junk debt above 15% — nearly double its levels in mid-January — it looks very much like a credit crunch is upon us.

At the same time, there’s reason to be fearful, too. Russia’s finance ministry has said it could sustain oil prices below $30 for as long as a decade. Setting aside a brief dip in the late 1990s, dollar crude hasn’t been at those levels in real terms since the 1973 oil crisis. In theory, that should be bullish for consumers of oil and bearish for purported substitutes, such as electric vehicles.

The real impact is likely to be more nuanced — and positive for decarbonization.

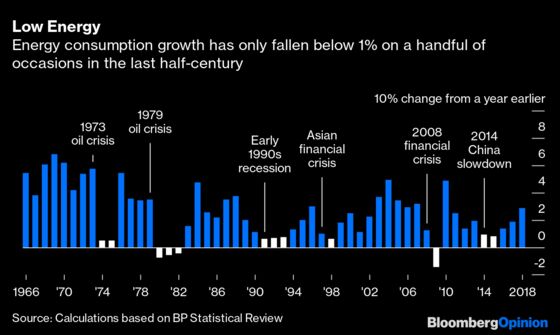

A key factor to bear in mind is that global downturns almost always throttle back energy consumption. There have only been six periods in the past half-century when annual energy demand growth has fallen below 1% on a sustained basis, and four of them resulted from slowdowns like the one we currently seem to be witnessing.

That’s only going to be a temporary help, since recessions don’t so much slow the pace of emissions growth, as defer the pre-existing path for a few years. But there’s reason to think that this time really will be different.

For one thing, unlike the solar panels that Jimmy Carter installed on the White House roof after the 1979 oil crisis, decarbonized alternatives are viable substitutes for fossil-fired energy now.

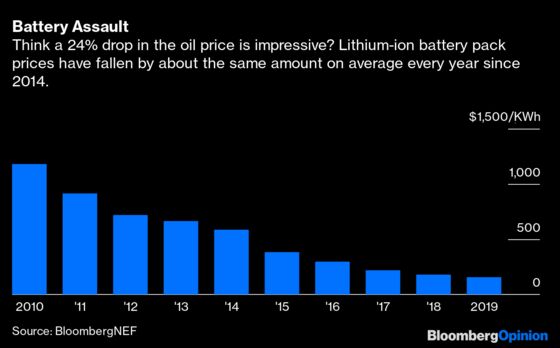

Take electric vehicles. Intuitively, Monday’s 24% drop in crude prices looks like obvious bad news for battery-powered transport. That overestimates how sensitive car buyers are to the price of fuel rather than that of the vehicle itself, though.

Running costs for electric vehicles in the U.S. are already less than half what they are for conventional cars — but as anyone who’s been into a Tesla showroom knows, not even subsidies have been enough to make drive-away prices competitive with equivalent gasoline- or diesel-powered vehicles.

We’re not likely to hit price parity on that front until battery packs drop below $100 per kilowatt-hour in the middle of this decade, according to BloombergNEF. Most people buying electric cars right now are either green consumers who aren’t likely to flip back to gas because the price of crude is low, or commercial users whose fuel and maintenance savings will be substantial enough that they’re unlikely to switch in a hurry.

Other segments of the oil barrel, such as the diesel and kerosene being used for powering ships and aircraft, as well as naphtha and ethane for making plastics, are likely to show even less response to the price crash. For several decades now, demand for oil has shown low and declining sensitivity to how much a barrel costs.

Another place where upfront expenditures are important is in the power industry. Wind and solar don’t use fuel, so the price of generation projects is unusually sensitive to one of the main early-stage costs — debt. One study last year comparing the drivers of solar power profitability in Europe found that lowering capital costs had almost as dramatic an effect as moving the project from Helsinki to Malaga, which gets about 50% more sunlight.

That’s good news for renewable project developers. The government bond prices that form the bedrock of borrowing costs are in uncharted territory, with 30-year U.S. Treasuries yielding less than 1% Monday and the yield on 10-year German debt at a record-low minus 0.856%. Right now, that flight-to-quality trade is still causing yields on corporate debt to spike — but if low benchmark interest rates become sustained as central banks try to nurse economies back to health, the cost of developing renewable projects will likely be lower for longer.

The major risk to this picture is how governments respond to the economic crisis, particularly in China. As we’ve written, Beijing has a habit of reaching for dirty industrial stimulus whenever growth is looking weak. That’s largely what reversed an unusual period in 2014 and 2015 when global emissions declined in spite of economic growth.

The world will almost certainly need help from its governments to recover from the current crisis. If the medicine they use is as dirty as China’s attempts at stimulus over the past decade, the systemic crisis for fossil fuels won’t be so much averted, as deferred to a later date.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.