What Is Really to Blame for the Repo Market Blowup

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Bank for International Settlements — the central bank of central banks — has weighed in with its analysis of what went wrong in mid-September when the U.S. repurchase market all of a sudden dried up (for the first time in a decade). It looks like it has missed the point.

While pointing the finger at a raft of different reasons and players, notably hedge funds, BIS doesn’t really answer the salient questions: Why haven’t the elevated funding rates that arose in September gone away and what can be done to prevent something like the original event from happening again?

There are obvious quick fixes with which the U.S. Federal Reserve and Treasury have responded swiftly, such as ensuring extra liquidity on tax deadline or auction payment days. But the wider problem is that the post-crisis regulation of banks has become too rigid, and that is going to need addressing at some point.

The repo market is the plumbing of the financial system where government securities are lent and borrowed for periods ranging from overnight to several months. This constant access to liquidity greases the wheels of government securities and the wider credit markets. Since the global financial crisis, cash has always been plentiful, so when repo rates all of sudden jumped as high as 10% in September, it was a rude awakening.

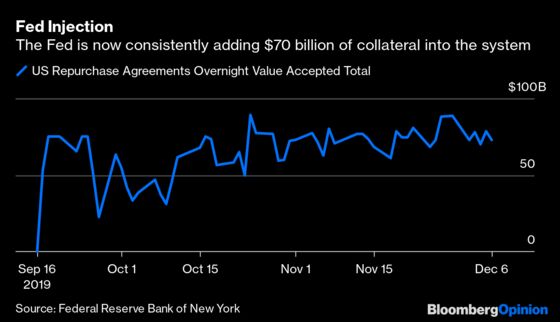

The Fed has been in full firefighter mode ever since — along with the U.S. Treasury — to try to make sure the spike in rates isn’t repeated over the critical year-end funding period. But short-term liquidity is no substitute for a proper long-term fix. With a Dec. 16 tax payment day looming (a day on which cash is naturally drained from the banking system), and with the repo rate over the year end more than double the Fed rate of 1.5%-1.75%, this is not proving to be a temporary problem.

It is in fact a confluence of systemic issues; it’s not just down to the too-swift reduction of the Fed’s bond holdings from the Quantitative Easing programs or a sudden abundance of new Treasury bonds for sale.

Similarly trying to blame hedge funds for their arbitraging activities misses the point: This is meant to be the world’s most liquid money market. Extending the overnight secured repo market to longer-term dates could rapidly ease much of this funding bottleneck.

The biggest four U.S. lenders own more than 50% of the Treasuries in the banking system but only one-quarter of all cash reserves. They have to hold this level of U.S. government bonds as high-grade collateral to satisfy regulatory requirements, but that restricts how much they offer into the repo market even when rates are temptingly high. This is a phenomenon that Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan Chase & Co’s chief executive officer, has been quick to point out.

Another question is why the rest of the U.S. banking system has backed away from the repo market? Again, this is down to regulation and market structure, which has made the repo market a less efficient use of banks’ capital. Regulatory measures put in place by the Dodd-Frank Act need revisiting.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.