(Bloomberg Opinion) -- I recently served on a jury in a criminal trial, and the experience gave me a different outlook on a contentious technology debate.

The defendant was a man accused of serially harassing his former girlfriend. Some of the evidence against him was a digital trail of thousands of phone calls to the woman at her home and work, and digital nude images of her that he sent to her family members and posted online.

Prosecutors and investigators downloaded reams of records from the man’s Android smartphone; they went through legal channels to confirm his ownership of the email account used in some of the online harassment; and they had logs of months of his outgoing landline calls to his ex-girlfriend. I wondered what would have happened if he had used different technology and communications to cover his tracks.

What if the defendant had used a recent model of the iPhone, which is considered more secure from excavation, or if he had used the Tor privacy software and an encrypted messaging app like WhatsApp to call, text and create online accounts for those nude images? There could have been fewer digital breadcrumbs of his harassment, and maybe I would have been less sure of his guilt. (My fellow jurors and I convicted the defendant of most of the charges against him.)

In the debate between digital privacy and public safety, I have mostly been on the side of technologists who say there’s no way to make software or hardware secure from the bad guys but breakable for the good guys to hunt down a drug dealer or terrorist. It doesn’t help that U.S. officials have reportedly overstated the number of locked smartphones they can’t access in criminal investigations.

Sitting in the jury box, I wasn’t so confident of my position.

I took my courtroom musings to the ACLU’s Jennifer Granick, an expert on digital privacy and a former criminal defense attorney. She said even if law enforcement and prosecutors can’t access every morsel of digital information when investigating a crime, there is often more than one way to compile the same evidence or corroborating information.

In this harassment case, even if there weren’t records from the defendant’s cellphone, the victim’s phones had records of the same communications. Law enforcement and prosecutors also obtain legal orders for customers’ phone calls or text message data from tech and telecom companies, cloud backups of smartphone activity, account information from websites, mapping app location, and other evidence. And people are convicted on eyewitness testimony, including before there was so much digital flotsam.

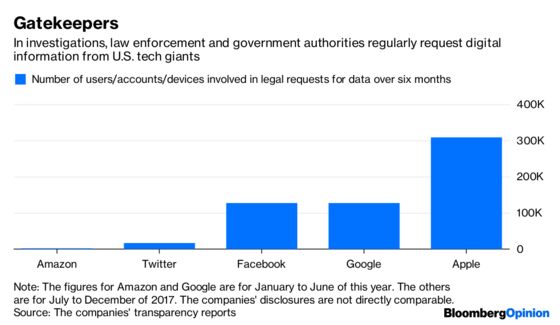

With or without encryption, there is a growing trail of our activity online and in the real world. We need to keep talking about how secure the technology is, how secure we want it to be, and how tech and telecommunications companies decide when to hand over our personal information. A small number of powerful companies make regular choices about when law enforcement has legitimate demands for personal information and when they may be overreaching. The public has little visibility into the decision-making of those digital gatekeepers.

As a generally law-abiding person and a journalist, I want my communications and digital activity to be as secure as possible from identity thieves, hackers and, yes, intrusion by law enforcement or legal authorities. But I also don’t want people to get away with crimes. Sitting on the jury, I felt willing to give up a little more of my personal privacy to make sure my fellow citizens are safe. Where to draw that line, though, is decidedly not black and white.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.