(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Mario Draghi, who steps down as president of the European Central Bank in October, deserves praise for almost single-handedly saving the euro. But thorny questions still remain about how well he oversaw the region’s banks, and one in particular: Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena SpA.

The Italian lender embodies problems that still plague many of Europe's banks: poor governance, weak profitability, and permissive regulators. In a column last month, I explained how customers and the public were unaware of how dire the bank’s situation was as it received a taxpayer-funded bailout to stay afloat.

But Monte Paschi holds a special significance for Draghi, too. As governor of the Bank of Italy between 2006 and 2011, he was ultimately responsible for regulating it. Crucially, the central bank signed off on Monte Paschi’s mammoth takeover of a rival at the peak of the financial crisis. It was a deal that eventually left the world’s oldest lender mired in scandal and bailouts.

How Draghi handled Monte Paschi’s most recent rescue matters to investors today. The ECB, which took over responsibility for supervising lenders from national central banks in 2014, was tasked with breaking domestic regulators’ grip on the industry. Yet in signing off on Monte Paschi’s $6 billion bailout in 2017, the ECB may have perpetuated those failings – and violated its own regulatory rulebook.

Monte Paschi wildly overreached when it bought Banca Antonveneta SpA in 2008 for 9 billion euros ($10 billion) in cash but with little due diligence. Markets were already peaking and, within months of the deal, the bank began hiding its losses by using complex derivatives – a practice that is now the subject of a criminal trial in Milan.

Italian prosecutors have accused Monte Paschi’s former chairman and general manager, as well as bankers from Deutsche Bank AG and Nomura Holdings Inc., of market manipulation and false accounting. Neither the Bank of Italy nor its employees are accused of any wrongdoing. The lender itself reached a plea bargain.

Still, looking back at Draghi’s oversight of Monte Paschi offers a window into how much progress European regulators have to make in order to become more effective stewards of the region’s banking system.

In 2010, just months after Monte Paschi had received a first round of state aid, Italy’s central bank became aware that the lender was hemorrhaging cash and had likely misrepresented its financial reports. The immediate consequences, though, weren’t visible. Top managers weren’t replaced until early 2012, a few months after Draghi had moved to the ECB. And it wasn’t until Bloomberg News reported on the derivatives transactions in early 2013 that they became public. The bank was forced to restate its accounts.

By the time the ECB replaced the Bank of Italy as Monte Paschi’s chief supervisor, its bad loans were rising and it had already received another infusion of money from the state. Draghi was presumably well aware of Monte Paschi’s problems, yet he and the ECB later came to the bank’s rescue. He declined to be interviewed for this column.

After injecting 8 billion euros of their own money during 2014 and 2015, Monte Paschi’s shareholders balked at putting in yet more funds. By the end of 2016, the bank had no choice but to seek state aid for a third time just to stay afloat.

For Monte Paschi to qualify for government aid, it had to satisfy regulators that it was meeting minimum capital requirements and that no taxpayer money would be used to offset existing losses. Pulling that off would have been difficult, however. According to an internal ECB report I wrote about last month, the regulators’ own analysts thought Monte Paschi hadn’t adequately provisioned for loan losses. Its likely insolvency should have made it a candidate for liquidation.

Did Draghi weigh in directly on any of the ECB’s deliberations involving Monte Paschi or offer a guiding hand on how to rescue the bank? All of that remains unclear, despite the fact that the ECB cleared the way for the European Commission, which formally has to sign off on such rescues, to authorize the bailout.

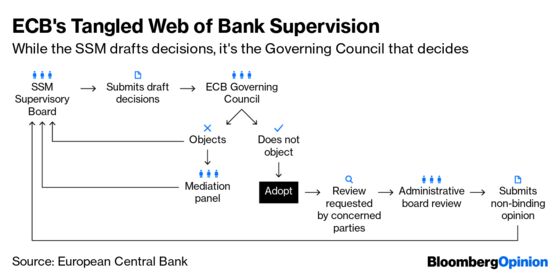

Overlapping regulatory responsibilities within the ECB blur the lines of accountability. For example, the Single Supervisory Mechanism, the part of the ECB that regulates banks, is only allowed to offer recommendations. It’s the bank’s Governing Council – whose members include Draghi – that has the power to approve regulatory decisions, including whether a bank qualifies for a bailout.

In response to my column last month, Markus Ferber, a member of the European Parliament, has asked the SSM to explain how the ECB decided to sign off on Monte Paschi’s bailout and if political pressure played a role.

Before he steps down, Draghi himself should set out how the supervisor came to approve the bailout despite stark warnings from his own inspectors. He should also provide a clear account of who was involved and what factors were considered when the ECB allowed the rescue to proceed.

A spokesperson for the central bank said the ECB had taken into account the findings of its team of inspectors when it gave the rescue the green light. The same official said that Monte Paschi was using its own funds to cover any past losses.

It wasn’t the only European bank to get into trouble, of course. Monte Paschi’s final crisis coincided with the implosion of two smaller Italian lenders. In the circumstances, imposing deeper losses on investors and inflicting more damage on the economy would have been politically tricky for the regulator.

All the same, the circumstances surrounding Monte Paschi’s rescue demonstrate that Europe still can’t adequately supervise and manage its ailing banks.

In an April report, the Commission itself identified significant flaws in how regulators bail out troubled banks such as Monte Paschi.

For example, the European Union’s rules don’t specify which authority should decide if a bank is solvent or whether it has properly recognized losses. They also doesn’t identify what metrics regulators should use when ruling on solvency.

“Further clarifications of the rules, based on future experience, could be helpful in tackling future cases and we will at that point assess whether changes in the legislative text are necessary,” the Commission told me by e-mail. The Commission also stressed that Monte Paschi’s rescue was carried out “in line with the applicable rules.”

Monte Paschi may have been an extreme test of the ECB’s new role as a bank regulator. But the bailout still casts a shadow on the ECB’s soon-to-be-departing president, Draghi. Italian taxpayers are still nursing losses from the rescue.

Before he hands over the baton to Christine Lagarde, Draghi has a chance to put any doubts to rest by offering a full account of his role in the Monte Paschi bailout. That would speak well of him and help his successors.

--Elaine He contributed graphics.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Elisa Martinuzzi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering finance. She is a former managing editor for European finance at Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.