(Bloomberg Opinion) -- On Dec. 25, 1991, unable to overcome the blow dealt by a hardline coup months earlier and by independence movements in Soviet republics, Mikhail Gorbachev resigned. The last Soviet leader wanted to reform communism, not replace it, but he was unable to contain the centrifugal forces his reforms had unleashed. The USSR, ailing and dismembered, came to an end.

“The old system collapsed before the new one had time to begin working,” he said in his final address, calling on Russia to preserve its hard-earned democratic freedoms. At Russia’s helm, Boris Yeltsin instead revived a system of personal power that has endured.

We asked some of the foremost economists, historians and observers of Russia and the Soviet Union why this collapse surprised so many, and what lessons today’s occupants of the Kremlin — and students of President Vladimir Putin’s Russia — should take from it.

Sergey Radchenko is a historian of the Cold War and Wilson E. Schmidt Distinguished Professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

The reason that few predicted Soviet collapse was that the Soviet Union outwardly appeared to be a mighty military power with an extensive security apparatus. Few observers understood just how little legitimacy the system possessed; that it was eaten away on the inside by the rot of corruption, by the loss of faith in ideology, by the dismal standards of living, and, lastly, by elite in-fighting. It was ultimately elite defection that brought it down — that, and its lack of overall legitimacy. What purpose did the Soviet Union serve, seeing that the building of communism was no longer in the cards?

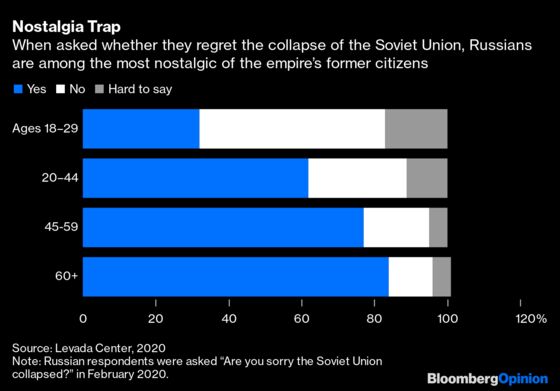

Putin has tapped into Russian nationalism — a much more potent force for national unity than the Soviets could ever have boasted. As a nation-state, therefore, Putin’s Russia is inherently more stable. Yet it is also plagued by some of the same problems the USSR had, including a deficit of legitimacy (in the absence of free and fair elections), corruption on a scale unseen in the USSR, stagnating standards of living and, as Putin ages, by elite in-fighting. So while Putin’s Russia is highly unlikely to fragment into quasi-independent principalities any time soon, the country has already entered a protracted crisis. The only question is what awaits at the other end, and how violent the transition period will be.

Sergei Guriev is professor of economics at Sciences Po Paris. He was rector of the New Economic School in Moscow until 2013.

It’s normal that most people could not predict that the Soviet Union, one of the two global superpowers, would fall apart. Such events are very rare in history. However, there were signs. If something cannot go on forever, it will stop — that’s [American economist] Herbert Stein’s law, formulated in 1986, and not about the Soviet Union. The Soviet economy could not generate productivity growth. Gorbachev had to borrow to provide stable living standards. The Soviet Union could not reform as the system was rigid. Eventually, the markets saw that the Soviet Union could not service its debt.

In more recent times, you can refer to the subprime mortgage crisis (although some people and some academic economists did predict it) and Greek crisis (there it turned out that a substantial part of Greek debt was hidden). Nobody expected a default within the euro zone.

Putin has learned a lot of lessons. First and foremost, Russia’s macroeconomic policy is much more conservative, inflation is under control, there are large reserves, a balanced budget and no external debt. Second, with all the domination of the state and ad hoc price regulations, Russia is still a market economy and is much more efficient and resilient than the Soviet one.

The world, however, should remember that as the Soviet regime collapsed, the Russian one can as well. The Soviet regime was ideological and collegial, Putin’s is personalistic. As Duma speaker [Vyacheslav] Volodin once said “No Putin — no Russia.” In this sense, this regime cannot last forever. Post-Putin Russia may be better or worse, but it will certainly be different.

Yevgenia Albats is an investigative journalist and editor of The New Times. She is also non-resident senior fellow at the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University.

It is rather remarkable that the Red Sunset was not projected by the army of Sovietologists, intelligence specialists and political scientists.

From my humble perspective, there are three primary reasons for such a failure. The first is understandable — it is a lack of factual life information gathered on the ground, as opposed to watching changes among the top Communist Party faces on the podium of Lenin's mausoleum during military parades.

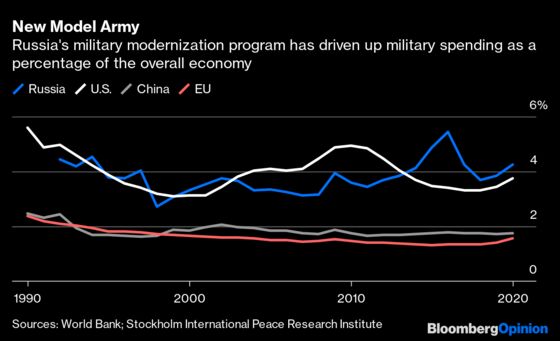

The second reason has to do with the over-politicization of academic analysis. For instance, Ronald Reagan’s famous “evil empire,” as he labeled the USSR (dissidents inside the USSR much appreciated it), which led to the so-called space wars — the escalation of the arms race — was considered hawkish by many in academic circles, as I found out when I came to Harvard for Ph.D. study. Yet, that hawkish policy put a rather important nail in the coffin of the Soviet overmilitarized economy and contributed to the regime’s collapse.

Finally, the third and the most damning reason, because of its long-lasting effect, was the practice of an over-personalization of politics at the expense of institutions. It was true concerning Gorbachev and the institutions of the USSR. In the same fashion, it is valid with the current Russian leader-turned dictator of the last 20-plus years, Vladimir Putin, who was seen by many specialists in the field as a pragmatist and acknowledged much more favorably than his old and often drunk predecessor, Boris Yeltsin. As a result, almost no one [20 years ago] foresaw danger in the fact that Putin was a representative of the most repressive and potent Soviet institution, the KGB. If one brought up the concern, saying that an institution based on brutal force rather than the rule of law took over Russia, the usual response (till the wake-up call in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea) was: George H.W. Bush was the head of the CIA.

The KGB’s triumphant comeback from oblivion was much overlooked and underestimated in the analysis of Russian development. The consequences are right there right now at the Ukrainian border, with 100,000-plus Russian troops about to invade a neighboring country.

Serhii Plokhy is professor of history at Harvard University and the director of the university’s Ukrainian Research Institute. He is the author of “The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union.”

The Soviet Union was known to policymakers in Washington and European capitals, journalists, and the public at large first and foremost as Russia — if not a European-style nation-state, then a sort of United States with republics instead of American states. During the Cold War, the two superpowers shared an animosity toward old-fashioned empires like that of Britain and wooed former imperial colonies that became independent nations between the 1950s and 1970s. But the Soviet Union, or “Russia,” was not considered an empire [at home] because its rulers claimed to have resolved the nationalities question of the pre-1917 Russian Empire by creating a unitary “Soviet people” on the basis of Marxist internationalism.

Thus it came as a major shock to the West that in 1991 the Soviet Union died the death of an empire, disintegrating along the ethnic boundaries of its 15 republics. Other aspiring nations within the Soviet Union, such as Chechnya, also struggled unsuccessfully to make their way out of the imperial womb. Western Sovietology might have been expected to predict such an outcome, but it paid almost no attention to the multiethnic composition of the Soviet Union, focusing instead on Kremlin politics, Russia, communist ideology and the military capabilities of the USSR. Few pundits, to say nothing of the Western public at large, realized that Russians constituted only slightly more than half — 50.8%, to be precise — of what Kremlin propagandists called the “Soviet people.”

According to the last census, Russians make up approximately 81% of the population of the post-Soviet Russian Federation. How many politicians and diplomats take this into account today, and how much of the general public knows that almost a fifth of today’s “Russians” are not ethnic Russians at all? Few at best. In many cases, the non-Russians live on ancestral territories that were annexed by St. Petersburg or Moscow in tsarist times, when it was the multiethnic Russian Empire. Given this Western blind spot with regard to non-Russians, many of whom do not consider themselves equals in the “Russian Federation,” we are in for more shocking political developments in the future.

Tatiana Stanovaya is founder and chief executive of political analysis firm R. Politik and a non-resident scholar at Carnegie Moscow Center.

There are at least three sensitive issues linked to the Soviet Union that have huge emotional meaning personally for Putin, and that the world should take into account when seeking to understand Putin’s motives. Firstly, he believes that Russia must be a unitary state and that the Soviet experience that implied national autonomies was a huge mistake. On several occasions, Putin accused Lenin of planting “a figurative bomb under Russian statehood by offering different nationalities their own territories and the right to secede,” “breaking down a 1,000-year-old state” — something that Putin believes he may restore and enforce. It shows how much Putin dislikes dealing with a federalized Russia and would rather deal with the country that governed as a single unit. It also demonstrates Putin’s strong fear of regional ambitions.

Secondly, Putin has been creating for years the cult of the state, meaning that the state as an institution has an unconditional priority over any other social or private interests and acts in the long-term national interest. That is why he has sought, for example, to rehabilitate Stalin’s rule — despite his personal condemnation of political repressions and mass terror, he believes that in some critical circumstances the state may have “emergency” powers and act far beyond the law if the “national interests” demand it. Believing in this right of the state to resort to extraordinary actions gives him the moral and historical justification for actions that may cross red lines of other world players. However, he also believes that states must agree between them on common rules under the principles of interdependence and guarantees of multilateral nonaggression.

Thirdly, Putin believes that the state’s priorities are sacred. He thinks that the state must be protected from “political” critics, as they make the state weaker and more vulnerable in a hostile environment. Since Putin considers Russia today to be a besieged fortress, under permanent geopolitical threat, he will severely suppress any real opposition — because he sees it anti-state, not anti-his own political regime. That also explains the return of political discourse praising some Soviet practices like the Young Pioneers, Komsomol, patriotic education etc. It does not mean that Russia may slip into the Sovietization of everyday life, but it surely will move further from democratic procedures and sooner toward coercive political and social consolidation than toward political diversity and open discussions.

Vladislav Zubok is professor of international history at the London School of Economics. His most recent book is “Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union.”

Observers and historians explain the sudden Soviet collapse in 1991 by long-term structural factors, such as a bankrupt planned economy, defunct communist ideology, Cold War pressures, and rebellion of nationalists in borderlands. As my book explains, the collapse was caused by Mikhail Gorbachev’s choices, above all by remarkably ill-designed economic reforms and rapid political liberalization. They created a perfect storm that engulfed the Soviet ship and its hapless captain.

Gorbachev’s economic reforms ruined the ruble and left the center without funds. His political-constitutional reforms triggered mutinies across the Soviet Union. The most fateful phenomenon of Rexit — separatism of the Russians, whose discontent found a leader in Boris Yeltsin. The Russians wrecked “the empire” that many thought was their own, and the central state. The USSR was killed by the implosion of the center, not by the pressures from the periphery.

Vladimir Putin drew major lessons from this story. He vowed to maintain macroeconomic stability at any costs and amassed huge financial reserves, as a safety measure. He is unwilling to open his coffers even in the time of pandemics. He dedicated huge resources, helped by oil prices, to restoration of state power, the army, police, and monopoly on violence.

Yet there is a lesson that Putin struggles with. The USSR was a confederation and it broke up irrevocably when its core, the Russian Federation, claimed its independence and sovereignty. Could the same in turn happen to this federation? The Russian constitution is now a one-way street: no exit for the subjects of federation, including the annexed Crimea and the conquered Chechnya. Yet risks remain. As the story of 1991 shows, the main source of instability for the state is not only rebellious national minorities, but also the Russian majority — when, for economic or some other historic reasons, it rebels against its own state.

Archie Brown is Emeritus Professor of Politics at Oxford University. His most recent book, “The Human Factor: Gorbachev, Reagan, and Thatcher, and the End of the Cold War,” won the Pushkin House Book Prize 2021.

I don’t accept all the premises of that question. The vulnerability of the multinational Soviet state in conditions of political pluralism was not a surprise. The real surprise was a Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev (even one whom I had from the early 1980s identified as a reformer), going so far as to embrace political pluralism both in theory and in practice. After that, all bets were off.

Serious specialists on the Soviet Union were well aware that there were some nations within the multinational Soviet state — in the first instance, Estonians, Lithuanians and Latvians — who had long yearned for independence. But prior to the perestroika years, it was clear that advocacy of separatism led only to the Gulag or even execution.

Gorbachev wished to hold the Soviet Union together, but differently. After initially underestimating how salient the “national question” would become, he tried to turn a largely formal federation into a genuinely federal state. However, by liberalizing and then embarking on democratization of the system, he had raised expectations and brought the pent-up repressed grievances and injustices of decades of totalitarian or authoritarian rule to the surface of political life.

A new freedom of speech developed by 1988-89 into a substantial freedom of publication. This allowed minority national aspirations for greater autonomy to be voiced. And contested elections in March 1989 for a new legislature enabled voters in the Baltic republics, Georgia and Western Ukraine to elect deputies espousing the national cause.

But the Soviet federal authorities still had a monopoly of the means of coercion — KGB, Army, and Ministry of Interior troops — and if Gorbachev had been as ready as his predecessors to use the overwhelming force at his disposal, separatism could have been stopped in its tracks. He was under great pressure from senior party-state officials, and from the military-industrial complex, to adopt such a crackdown. As the most pacific leader in Soviet history, he tried to hold a reformed Union together by negotiation and agreement.

Gorbachev might have succeeded in keeping most Soviet republics (though, in the absence of coercion, minus the Baltic states) in what he called a “renewed federation” had not Boris Yeltsin demanded Russian “independence” from the Union. It was paradoxical for a Russian leader to spur the breakup of a Soviet Union that was, in many respects, a Greater Russia. But Yeltsin’s overwhelming ambition was for political power and to take Gorbachev’s place in the Kremlin.

It was predictable that Yeltsin’s actions would lead either to the breakup of the Soviet Union or to the federal authorities cracking down hard on the fissiparous movements. A Gorbachev who resisted using the coercive force at his disposal could have been replaced by those with no such scruples.

But the hardliners left their coup too late, putting Gorbachev under house arrest in August 1991. That was two months after Yeltsin had been elected President of Russia, thereby acquiring a popular legitimacy that enabled him to defy them. And the coup plotters themselves had been sufficiently affected by the changed atmosphere brought about by Gorbachev’s reforms that, unlike Deng Xiaoping in Beijing in 1989, they were not ready to massacre hundreds of people in order to restore the traditional order.

Expert observers were aware of the various forces pulling in different directions in 1990-91, and of the real possibility of Soviet breakup. But which forces would prevail depended on decisions and contingencies that were unpredictable even for the main political actors themselves. Both Gorbachev and Yeltsin were surprised by the August 1991 coup (which accelerated the breakup of the Soviet Union that it was meant to prevent), while the putschists had not expected their takeover to collapse within a few days. It would be odd, therefore, to expect anyone else to predict the outcome of events that could have taken a quite different course.

More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion:

- Skewed History Is Becoming a Global Superweapon: Max Hastings

- Thirty Years Gone, the Soviet Union Is Not Quite Dead: Leonid Bershidsky

-

For China, USSR’s 1991 Collapse Is Still News It Can Use: Clara Ferreira Marques

- How Kissinger’s Secret Trip to China Transformed the Cold War: Hal Brands

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.