(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There has been a lot of pain for WeWork in the last few months. It doesn’t get easier from here.

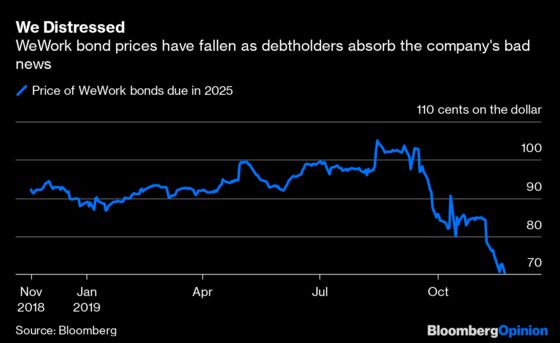

The office leasing startup has been on a wild ride. Its planned initial public offering was derailed in September by investors’ shock at the company’s red ink and self-dealing by its chief executive officer. WeWork was close to running out of cash before an emergency financing last month. WeWork’s valuation withered to less than the investment money it had collected.

Masayoshi Son, the SoftBank Group Corp. founder and WeWork’s biggest backer, said turning around the startup would be “simple.” It isn’t. To be viable, WeWork must continue to slash costs, reassure a nervous workforce, build out hundreds of new offices with uncertain financial prospects, possibly mollify tenants and landlords who might be unsettled about working with the company, reevaluate its office portfolio and stabilize declining average rent payments and occupancy rates.

It will take skill, luck, tough choices and the persistence of SoftBank for WeWork not to die. The degree of difficulty shows how hard it is to fix a company that expanded and operated without regard for what would happen next.

For now, WeWork’s five-alarm fire is doused. SoftBank agreed last month to move up a $1.5 billion investment it had planned to complete next April. SoftBank is also backing a plan — not fully fleshed out — for WeWork to borrow $3.3 billion and obtain a backstop for as much as $1.75 billion more.

The bottom line is that WeWork will be dependent on SoftBank, which has already expressed regret for putting so much faith in WeWork and Adam Neumann, the co-founder and ousted CEO. Second thoughts inside SoftBank about a stock repurchase that is part of WeWork’s bailout make me question SoftBank’s commitment to see through a multiyear WeWork turnaround.

Assuming the bailout goes through, WeWork also must get its costs under control — and that comes at a high human toll. WeWork said last week that it’s laying off 2,400 people, or nearly 20% of the more than 12,500 employees it had at the end of June. The company is likely to shed more employees as WeWork offloads side businesses.

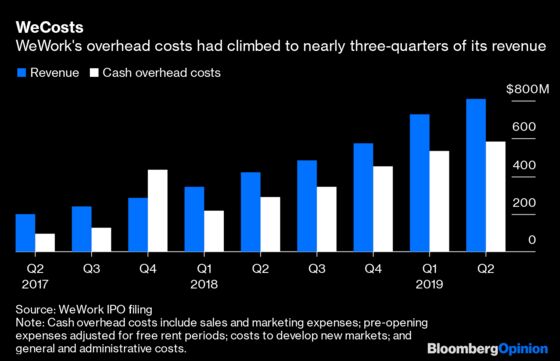

Fitch Ratings, using different numbers, has calculated that WeWork’s overhead costs need to come down from about 60% of its revenue to a “low double-digit percentage” in the coming years. Fitch figured it would take about $1 billion in cost reductions to put the company on sounder footing. WeWork on Friday outlined management changes to employees and said the company has a target to generate positive cash flow by 2023. That’s a long time to be financially unsustainable. The company appears to have burned through $1 billion of cash in the most recent quarter.

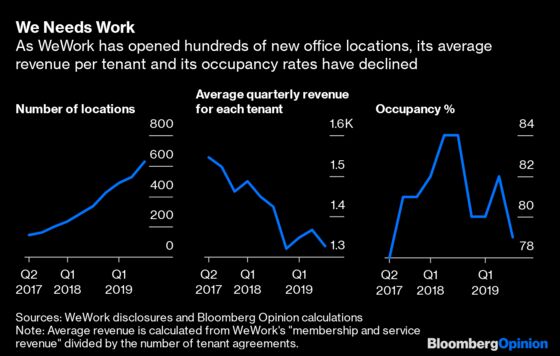

But WeWork can’t just cut its way to health. It also needs to spend to bring in revenue from its rapid expansion. In the 12 months ended in September, the number of WeWork locations ballooned from 334 to 625, according to a company presentation to bondholders. It’s unclear how many of those offices have paying tenants, but it’s likely the company must revamp a chunk of those offices to WeWork’s specifications and perhaps wait out free rent periods for new tenants.

Each fresh tenant, however, comes with an uncertain financial profile. WeWork in its disclosures to prospective IPO investors said it had been expanding into cities and countries where rents tend to be lower than they are in more established WeWork markets such as New York, London and Washington. WeWork on average generated $1,522 from each paying tenant in the third quarter of 2017 and $1,327 for the three months ended in September.

The percentage of its open desks with paying tenants has also dropped, including at locations open for more than two years. The company needs to stabilize, if not increase, occupancy rates and per-location revenue. This is a tall order. WeWork’s drama may also make tenants wary of signing or re-upping.

WeWork has signaled it is reassessing office deals it signed or was considering. The company may be smart to wriggle out of unpromising leases, but that could force WeWork to pay penalties. Walking away from deals may also make other landlords wary of renting their buildings to WeWork or less eager to give it breaks on rent and help with construction costs. Having fewer locations, or locations leased on less generous terms, puts a ceiling on potential future rental income. The company as of June 30 had committed to making $47 billion in lease payments in coming years.

WeWork’s new executive chairman also told employees about a planned change to its business model, according to the Financial Times. Instead of signing long-term office leases, carving them into chunks and re-leasing them for shorter-term rentals, WeWork wants to manage commercial properties for landlords in most cities. The business approach is similar to that of hotel chains such as Hilton and may be a more viable strategy — assuming landlords go along. But WeWork will still need to clean up the mess from all the leases it signed in its expansion binge.

There are good ideas at the heart of WeWork. Businesses don’t want to track down office space, commit to long leases and deal with the hassle of keeping an office running. But all that WeWork has proved is that it’s possible to build a big business with some innovative approaches as long as it spends money like there’s no tomorrow. Now that WeWork is trying to last, there is a lot of hard work and many difficult choices ahead, and there are no guarantees that WeWork can make it work.

My rough numbers: If WeWork eventually reduces its payroll by 4,000 people, at an average compensation cost of $150,000, that works out to $600 million insavings. That doesn't factor in severance and benefits that WeWork has said it will make to people it is laying off.

My calculations include WeWork's reported operating expenses for its locations before they open to tenants, minus WeWork's adjustments to account for periods where it doesn't owe rent to landlords on buildings without tenants. The costs also include WeWork's sales and marketing operations, costs to scout and develop new buildings and new marketsand general and administrative costs.

WeWork's IPO filing said there were 214 WeWork locations at the end of June that hadn't yet opened for tenants, compared with 99 at the same point in 2018.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.