We’ve Seen the WeWork Saga Before. It’s Called Domo.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The company badly needs an initial public offering to fund its cash-burning business. The chief executive is brilliant at pitching investors but also has ironclad power and milks his company to the benefit of himself and family members. Early financial backers are taking a bath on their investments.

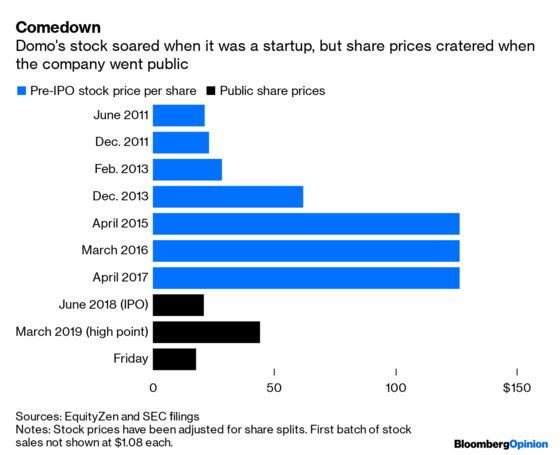

That description fits WeWork, the controversial office-leasing startup that is having a hard time with its planned IPO and may now face a boardroom fight to potentially remove its CEO. It also applied — minus the possible coup — to Domo Inc., a software company that held up in the first six months after its rocky 2018 market debut and then crashed. If those who owned shares of Domo before the IPO still have them, their investment has shriveled by as much as 86%.

Domo started in 2010 and was buzzy in cloistered tech circles. The founder and CEO, Josh James, helped start a marketing analysis startup called Omniture in the relatively early internet era and sold the company at a large windfall for himself and Omniture’s investors. James has said he started Domo to address a need for corporate bosses to easily keep tabs on basic metrics, such as real-time store sales or the risk of clients quitting.

At Domo, James had a knack for charisma and raising money. Domo sold $700 million in stock and borrowed $100 million more. The company’s investor list and its board were stacked with respected technology startup backers including IVP, Benchmark, GGV and the investment-fund giants BlackRock and T. Rowe Price.

By about 2015, Domo appeared to have trouble. Some of its investors marked down the value of shares purchased in private transactions. Last year, when Domo made its finances public for an IPO, it was eye-opening.

The IPO document said that Domo needed a public stock sale or another source of cash urgently or it might have to slash costs to avoid running out of money. (A subsequent investor document toned down the urgency somewhat.) The pace of revenue gains was good but not great, and Domo was spending a fortune to grow.

The filing disclosed that James had 40 times the power of other stockholders, which was notable even in this era of superpowered voting stock held by tech company founders. James had also billed Domo for use of his personal jet, and businesses part-owned by him and affiliated with two of his brothers had catered food for Domo and sold furnishings to the company.

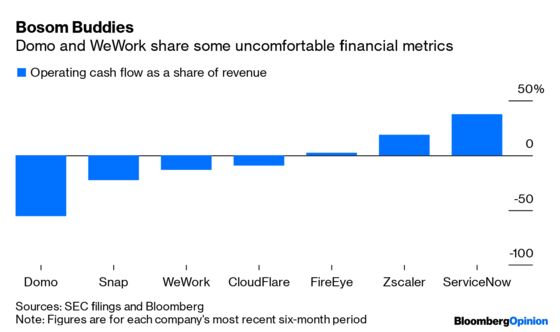

The combination of Domo’s heavy spending, precarious financial condition and the CEO’s self-dealing made me wonder how a company could have gone off the rails so badly without any apparent accountability imposed by supposedly savvy investors. It’s not an unfamiliar tale for young companies, but Domo seemed like an outlier — until WeWork took the worrying qualities of Domo to a whole other level, that is.

Like WeWork, Domo scaled back some of the financial arrangements with the CEO. Its IPO got done, but not happily. Domo’s early backers had purchased stock at an effective price as high as $126.45, and the company sold IPO shares at $21 each. Almost every investor who bought stock in the company’s history had nothing to show for it.

Once it went public in June 2018, Domo put up quarterly results that were healthy for a while. The share price rose to a high of $44 in March. Things started to fade after that, and Domo’s stock price tumbled this month after the company cut its financial forecast and shook up its business and sales strategies. Believers in Domo remain, and other young software companies haven’t figured out the right approach to selling their products.

But the same red flags are still there. Domo has been spending about 77 cents in sales and marketing costs for each dollar in recorded revenue. It’s among the least efficient business software companies with its sales and marketing spending. Domo’s cash-burn rate has improved but remains high. Executives said recently that the company is committed to becoming financially self-sustaining and is willing to cut costs to get there, according to JMP Securities. That’s not the usual condition for a growth company.

Investors don’t learn lessons when they should, but Domo is a cautionary tale for WeWork and others. Companies with wobbly financials, a track record of imprudent spending and a history of self-dealing don’t magically change when they go public — no matter if they are humbled by a valuation haircut or pare back some of the excesses.

There are limits to the comparison between Domo and WeWork. I have never, ever seen a company like WeWork, and a potential effort to remove a founder-CEO on the eve of an IPO is an unimaginable drama. But it remains a useful caution that Domo is a nine-year-old company that has not delivered anything good for investors. The company’s wayward operation and poor governance were exposed when it had to disclose them to the world.

When people howl about unseemly financial arrangements with a CEO or a lack of accountability, it’s not because a company is violating a meaningless checklist of good governance. It’s because those are obvious hallmarks of companies built on weak foundations.

I sincerely apologize to Leo Tolstoy.

Domo noted that the company believed it got "favorable pricing" for James's jet and the catering and furnishings provided by his companies. That was not the point.

The pre-IPO stock prices have been adjusted for stock splits.

Like many companies priced for growth, Domo's share price has been volatile and could shoot back up just as it has crashed recently.

Another difference between Domo and WeWork: Domo's category of subscription software is a business model that is well understood and (for now) loved by stock market investors. No so much WeWork.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.