WeWork Isn’t Solving Its Biggest Problem

Governance changes may help win backing for its IPO, but won’t change a fundamentally flawed business model.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- WeWork is slightly less WeWork, but it's still very WeWork.

The commercial real estate/wannabe tech company shed a few of its egregious provisions that gave Adam Neumann, the company's co-founder and chief executive officer, an unusual measure of authority over his company – including the power through his wife to pick his replacement from beyond the grave. WeWork also agreed to cut in half the voting power of Neumann’s stock, and he will hand to the company any profits he receives from real estate properties he had owned and leased to WeWork. If you’re new to reading about this company, yes, all of those eyebrow-raising things happened at WeWork.

Neumann is an extremely effective pitch man for his company, but it's understandable that potential investors in WeWork’s initial public stock offering reportedly balked at buying wildly valued shares of a company with a short operating history, unsteady unit economics, a governance structure that favors one person above all others, a history of questionable spending and – oh yes – an obligation to pay nearly $50 billion in lease payments in coming years.

Neumann's willingness to dump some of the terms that enriched or empowered him shows how badly WeWork needs the money to fund its ambitious, or perhaps unsustainable, business. The company burned $2.2 billion in cash last year, and those conditions aren't likely to change soon. If it wasn't able to get an IPO done, WeWork would have lost out on as much as $10 billion in fresh cash from the stock sale as well as bank loans that are in part contingent on the IPO. That is a lot of motivation to make promises, but not too many.

“Corporate governance is important to our company,” is a sentence written in WeWork’s updated IPO prospectus filed Friday. If that were true, of course, we would never have gotten to this point.

WeWork and Neumann will likely have to take the psychological blow of a steep valuation haircut in an IPO, although it remains to be seen how much. Bankers months ago were talking about WeWork meriting a stock market value of as much as $65 billion; it now may be significantly south of $20 billion.

WeWork's valuation as a private company was always a fiction written by Neumann and his biggest financial backer, the Japanese telecom giant SoftBank. But assuming WeWork goes public at a significantly reduced number to its fictional valuation, it nevertheless could have real consequences for SoftBank's relationships with partners in its massive tech-focused investment fund, and for WeWork employees who might be holding overvalued stock.

Even after the changes WeWork was forced to make, this is still a company controlled almost entirely by Neumann – who seems fine using it as a foundation to collect many hundreds of millions of dollars from personal loans or WeWork stock sales – that’s run with the discipline of bears escaped from a circus and structured to funnel profits and minimize taxes for Neumann and a tiny cadre of others. As I said, WeWork is still very WeWork.

In the outrage that exploded since WeWork released its IPO prospectus last month, there has been justifiable blame on Neumann and on SoftBank's bazooka of cash for letting WeWork get so very WeWork. Let's not stop there. There is plenty of blame to spread around.

WeWork has a legion of experienced investors who poured more than $12 billion into the company, sat on its board of directors and apparently bought Neumann's vision and empowered him to do whatever he wanted. Let’s point fingers at JPMorgan Chase & Co. and other banks that lined up to lend Neumann money, presumably with dollar signs in their eyes hoping to do business with his company. When no one wants to kill or even slightly inconvenience a potentially golden goose, it can’t be a surprise when the goose makes an utter holy mess.

As my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Matt Levine wrote recently, the oddity of WeWork is that it actually had to make compromises as it graduates from startup to a public company. This hasn't been typical in the last few years as young and cool companies from Snapchat to Lyft and Slack started going public. They've been able to stay the same insulated, founder-empowering startups, giving the new owners of their companies as little influence as possible while basically continuing to do whatever they wanted – just as they had when they started in a proverbial garage. WeWork broke that mold.

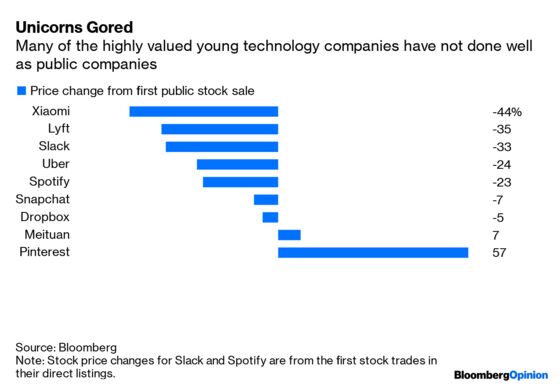

WeWork still might do just fine as a public company. Or not. The tepid at best public market reception to Uber, Lyft, Snap and others shows that stock investors aren't solely persuaded by the bright shiny object of fast revenue growth, if a company doesn't have a proven business model or can't competently execute its business plan.

However the IPO goes, WeWork's difficulties hitting the stock market should – but probably won’t – spark soul searching among those who start companies and support them with financing in Silicon Valley, on Wall Street and far beyond. Some big ideas have bloomed in the last decade that wouldn’t have been possible without the easy availability of cash for young tech companies.

But I have grown increasingly worried that the limitless cash has created a generation of bad companies. When we look back at the "unicorn" wave of the 2010s, we may see companies puffed up by easy money and limping along on flabby financials, with cash spackling over the glaring holes in their business models. I worry the easy money has ossified in young companies a lack of accountability, with egotistical and insular leadership.

That is the downside of the free-cash era for unicorns. WeWork may be the apotheosis of the phenomenon, but it is far from a singular example of startup rot.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.