Wall Street Fears Elizabeth Warren for the Wrong Reasons

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Wall Street should fear Senator Elizabeth Warren, but not for the reason it thinks.

Some of Wall Street’s biggest stars have howled recently about how Warren would wreck the U.S. economy and the stock market if she were elected president or merely continued to make strides in that direction. Billionaire Paul Tudor Jones predicted last week at the Robin Hood Investors Conference in New York that the S&P 500 Index would decline 25% and that U.S. economic growth would be cut in half if Warren were to win. Leon Cooperman, Rob Citrone and Jeffrey Vinik have also said that the market would react negatively.

Those fears are misplaced. Presidents have far less control over the U.S. economy than many think. Most recently, President Donald Trump tried to boost the economy with his sweeping Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, but its effects have been negligible so far. Also, no one can reliably anticipate the stock market’s reaction to events. Instead, Wall Street ought to worry about what Warren would do to the rarefied world of private equity, particularly leveraged buyouts, or LBOs.

LBOs are simple transactions in concept, similar to buying a home. LBO firms acquire companies by putting down a small percentage of the purchase price and borrowing the rest. That liberal use of leverage magnifies returns, which is the main reason LBOs have historically been among the best performing investments. They can also play a useful role. When a public company wants to go private, a firm with multiple business lines wants to shed a division or a business owner wants to cash out, LBO firms are often the buyers.

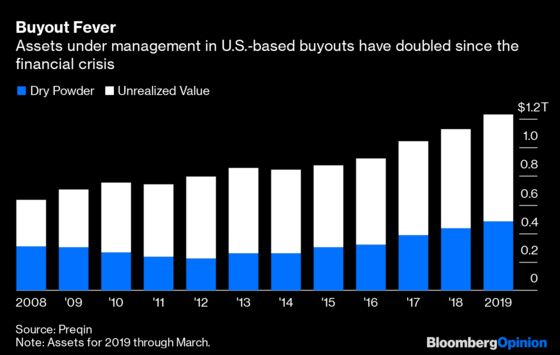

The problem is there’s more money chasing LBOs than deals to accommodate it. Roughly $1.2 trillion was invested in the strategy as of March, according to research firm Preqin, double the amount invested across all private equity strategies in 2000. The unsurprising result is that companies are fetching higher purchase prices, if investors can find deals at all. In a 2018 survey, private equity firms cited high valuations, a scarcity of deals and intense competition as their biggest challenges, according to financial data company PitchBook.

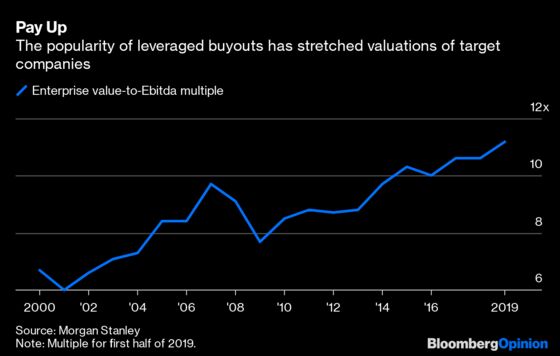

The numbers bear it out. In the first half of 2019, LBO investors paid 11.2 times Ebitda, or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, according to Morgan Stanley, nearly 70% more than the 6.7 times they paid in 2000.

LBO firms have been able to offset higher purchase prices with help elsewhere. For one, interest rates have declined significantly over the last two decades, with the 10-year Treasury yield falling to less than 2% from close to 7% in 2000. Investors have demanded little more for low-quality debt in recent years, which features prominently in many LBO deals. Those low rates have allowed LBO firms to borrow or refinance more cheaply. In addition, the U.S. has enjoyed the longest economic expansion on record since 2009, which has helped bolster their portfolio companies’ profits. Third, rising valuations have allowed LBOs to sell their investments at ever higher multiples.

Those tailwinds could evaporate quickly, but that hasn’t dissuaded investors, at least so far. They still expect higher returns from private equity than they do from U.S. stocks and bonds and a smooth ride, given that private assets are sheltered from turbulent public markets. Those perceived advantages have made private equity a fixture of institutional portfolios and, increasingly, those of individuals.

To accommodate the flood of investment, LBO firms are venturing farther from their traditional turf and into every conceivable corner of the economy, including pet stores, doctors’ practices and newspapers. The industry says its expanding reach leaves companies better off, but there’s mounting evidence that companies acquired through LBOs are more likely to depress wages, cut investment or go bankrupt, in many cases because of their debt load. When that debt proves too burdensome, workers and their communities and the taxpayers who inevitably support them all lose, while LBO firms still collect their fees and dividends.

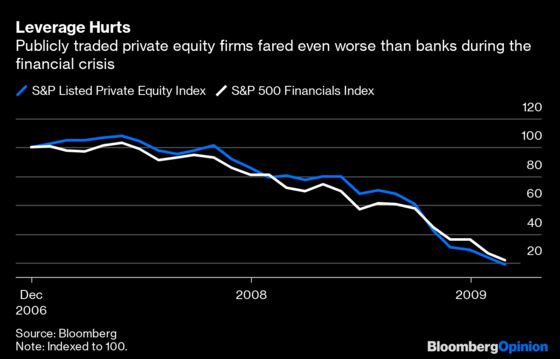

Leverage is risky business, as the 2008 financial crisis laid bare, and the growth of private equity is spreading that risk well beyond its small sphere of well-heeled investors. Numbers for private equity are famously guarded, but one way to get a sense of the risks and rewards that come with the industry’s use of leverage is by looking at the stock performance of publicly traded private equity firms.

The S&P Listed Private Equity Index, which includes industry titans Blackstone Group Inc., Apollo Global Management LLC and KKR & Co., tumbled 82% from peak to trough during the financial crisis, including dividends. That exceeded the 79% decline for the S&P 500 Financials Index, the sector whose excessive use of leverage triggered the crisis, and the 51% decline for the S&P 500. Since the crisis eased in March 2009, however, the private equity index has outpaced the financials index by 1.3 percentage points a year through October and the S&P 500 by 2.4 percentage points.

That brings us back to Warren, who has said that “private equity firms are like vampires — bleeding the company dry and walking away enriched even as the company succumbs.” Warren has also called private equity “legalized looting” that “makes a handful of Wall Street managers very rich while costing thousands of people their jobs, putting valuable companies out of business and hurting communities across the country.”

Warren introduced a sweeping bill in July titled — what else — the “Stop Wall Street Looting Act” that would, at the very least, fundamentally transform the industry. Her proposal would ratchet up the potential liability of private equity firms by putting them on the hook for debts of their portfolio companies, holding them responsible for certain pension obligations of those companies and limiting their ability to collect fees and dividends. It would change tax rules to deny private equity firms preferential rates on the debt they put on portfolio companies and close a loophole that allows them to pay lower taxes on investment profits. It would also modify bankruptcy rules to make it easier for workers to collect pay and benefits and harder for executives to walk away with bonuses.

Steve Biggar, an Argus Research Corp. analyst who covers private equity firms, called Warren’s plan an “industry-destroying proposal.”

Of course, the industry is just as vulnerable to a sustained downturn or higher interest rates, given its cocktail of leverage and high valuations. In the meantime, as more Americans encounter the fallout from failed LBO deals, support for regulation of private equity is likely to grow. And if Warren occupies the White House, she may well lead the charge.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.