(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Marrying the interests of issuers of new debt with yield-starved investors desperate for access to bond sales is an increasing problem for investment banks. This is a lucrative and high-profile part of bank business that needs to work better because the current feeding frenzy is distorting markets.

According to the Wall Street Journal, several European countries are capping some of the frothiest hedge fund orders of sovereign debt. This is understandable as issuers like to sell to investors who’ll hold their bonds for a longer period, and the current free-for-all makes it hard to tell the keepers from the hit-and-run crowd. Given the rampant demand for high-quality debt, genuine buyers often feel cut out of the process.

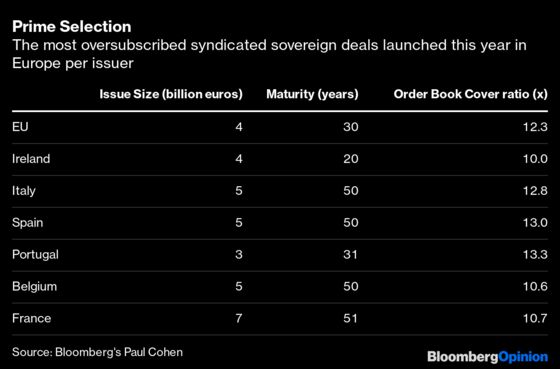

In a vivid example of the wall of money chasing new bonds, a two-tranche deal in October for the European Union received 233 billion euros ($283 billion) of orders for 17 billion euros of bonds sold. And as an example of the flakiness of buyer commitment, the order book on a 10-year deal for Spain in January more than halved from a peak of 130 billion euros as the terms were tightened. No wonder sovereign issuers want more sense of control over who’s buying their debt.

There’s certainly scope to improve an inefficient and opaque new-issues market that gives too much power to those in charge of the sales process: the investment banks and specifically the lead bank on the deal.

Almost all syndicated deals (where governments bring in a panel of banks to run the sale) use the so-called “pot system” where — in theory — all members of the panel see all the orders. However, the decision on how much to allocate to each buyer is still usually made by one bank, the “top left” bookrunner in the jargon. There’s some transparency but this approach increases the chance of giving preference to the bank’s most lucrative clients as a reward for business elsewhere.

I’m not saying hedge funds should be squeezed out. They provide liquidity and a small amount allocated to fast hands can make for a more active secondary market. European Union issuers need a wide range of investor access in good times and bad, as Italy well knows. But a more level playing field can only be achieved if everyone knows roughly how the game is ordered.

The order allocation of hot new bond issues has long been a murky area of the capital markets. Which client gets favored and how is a closely guarded secret on Wall Street, but dissatisfaction is growing on all sides — more so now that every new European sovereign bond sale seems to be breaking records on order books.

Issuer unhappiness ought to be a wake-up call for the bankers that receive juicy fees to manage and sell what are often highly liquid benchmark bonds. The regulatory authorities may take much more of an interest in how and where this debt is placed. Under the MiFID II regulations banks have to agree the allocations with the issuer. Any inflated-looking orders are supposed to be reported, but there’s little evidence of this happening.

There are simple questions the banks can ask themselves: Is this a realistically sized order for the usual pattern and scale of each client, and does the client have the funds to make good on their order? Capping the maximum-sized order for the hottest deals is also prudent and would improve a secondary market whose lack of liquidity is cited as one of the biggest dangers in the financial system.

Too many huge deals are being sold in huge chunks to huge funds. If everyone wanted to sell at once, the banking system may not have the balance sheet to absorb it. This could be easily remedied if there were a genuine desire to improve visibility for all. There are plenty of trade bodies, such as the International Capital Markets Association, that could provide a simple and adaptable guideline template for each deal.

This would ideally create enough flexibility to better match the interests of issuers with all investors, and it wouldn’t compromise the investment banking model. If the industry doesn’t change of its own volition, the regulators will make it.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.