Wall Street May Rue China’s Opening

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Wall Street, be careful what you wish for. Getting that level playing field you want in China might backfire — and not just because its stock market is in the dumps.

Shortly after President Donald Trump’s visit to Beijing last year — when he complained bitterly about China’s unfair trade practices — officials decided to relax regulations limiting foreign ownership of banks and securities firms. Overseas players could start holding 51 percent of domestic brokerages, up from 49 percent — a cap that will be eliminated after three years.

The only global firm that’s managed to gain control of its Chinese investment bank is HSBC Holdings Plc, which got approval to set up a 51 percent-controlled brokerage in Guangdong province before Trump met with President Xi Jinping. The development had little to do with diplomacy, and rather came down to the firm’s longstanding Hong Kong ties, which grant it more flexibility than foreign peers.

So far, UBS Group AG, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Nomura Holdings Inc. have submitted applications for majority stakes in their Chinese joint ventures, while Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Bank of America Corp. and Citigroup Inc are still waiting.

The laggards may have a case for inaction.

There are all kinds of roadblocks facing foreign firms eager to secure a majority holding. Some joint ventures have non-financial owners, whose stakes are limited to 33 percent (that means more partners, or shopping within a limited pool for financial ones). Another challenge is that global companies have to be clear of certain legal and regulatory infractions to qualify. How any bank could check that box in a post-2008 world that’s seen billions of dollars in fines is a mystery.

But one of the biggest hurdles faces global and local firms alike: the requirement that the majority shareholder have a net asset value of at least 100 billion yuan ($14.4 billion). For a foreign-controlled company, that means its domestic entity would have to meet this threshold.

This is no easy task for many entrants, including Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, which run their Chinese businesses out of Asian entities that wouldn’t qualify. Banks also have cut their risk weightings overseas in the wake of the financial crisis. The only joint ventures that might be exempt are firms focused on wealth management, like UBS.

It’s even a big ask for local brokerages, given the previous requirement was just 200 million yuan, according to Fan Lei, a lawyer at Baker McKenzie’s Chinese affiliate FenXun Partners. The rule was intended to weed out all those small, weak brokerages that rose from the ashes of struggling coal miners or steel producers in recent years and began selling wealth management products.

If high capital requirements don’t get foreign firms, levies on their staff might. Global companies have been caught in Beijing’s efforts to raise its tax base as the economy slows, and the government eases the burden on the poor and middle class.

Previously, foreigners who qualified as tax residents — those living in China for at least a year — could skirt the levy on overseas income by leaving the country for one month every five years. Now, China is looking into lowering that one-year threshold to 183 days. Global banks, hoping to parachute in experienced and trusted executives from overseas, will start hurting if they have to stump up those costs, says Lyndon Chao, head of equities for Asia Securities Industry & Financial Markets Association in Hong Kong.

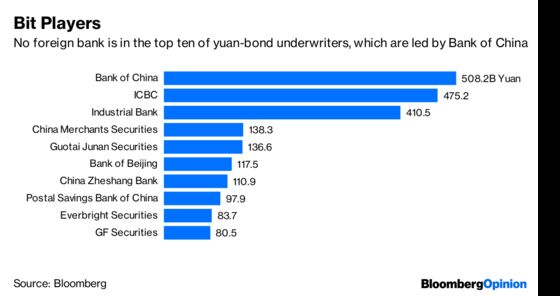

The long wait for approval might not be such a bad thing. Despite its potential, China’s stock market isn’t easy pickings for foreigners, and regulators increasingly are asking brokerages to avoid issuing negative reports. While procrastinating may risk loss of market share to already-dominant local players, and even Beijing’s goodwill, waiting out the three years could eliminate the need to find a Chinese partner willing to take the back seat. By then, things may be better.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nisha Gopalan is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and banking. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones as an editor and a reporter.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.