(Bloomberg Opinion) -- One day after tumbling the most since 1987 by plunging 11.98%, the S&P 500 Index regained its footing and surged by an impressive 6%. The gains came thanks to moves by the Federal Reserve to support the market for short-term corporate debt and more details on the government’s plan to keep the economy from collapsing amid closures intended to mitigate the widening coronavirus pandemic. Both are positives, for sure, but markets won’t truly start to recover until one key question is addressed that no one on Wall Street is qualified to answer.

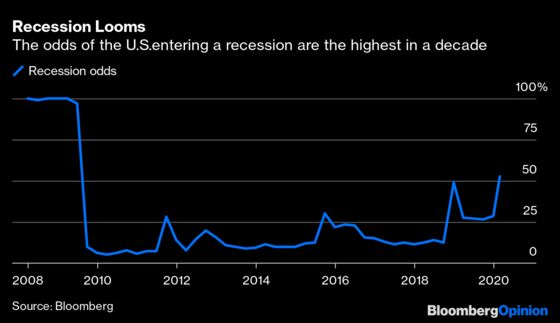

Rather than how far the economy may drop or whether it’s time to wade back into equities to do some bargain hunting, Deutsche Bank strategist Torsten Slok wrote in a research note that most of his client conversations at the moment center on questions around best practices across countries for limiting the spread of Covid-19. With strategists fielding queries better suited for doctors, it’s clear that items such as the level of interest rates or price-to-earnings ratios are unlikely to matter all that much until more fundamental questions about the coronavirus crisis have some clear answers. “Not even health experts understand what this is or where it is headed, and that is the worst possible outcome for investors,” Jim Paulsen, Leuthold Group Inc.’s chief investment strategist, wrote in a research note. “Give me bad news any day over complete uncertainty.” The point to all this is that the wild swings seen in equities in recent weeks — with Tuesday marking the seventh straight day that the S&P 500 notched a move of at least 4% — will likely continue no matter how much money is thrown into the financial system by central banks and governments. Until a real solution to halting the spread of the coronavirus is developed, such moves will be viewed by markets as little more than triage.

SPEAKING OF TRIAGE

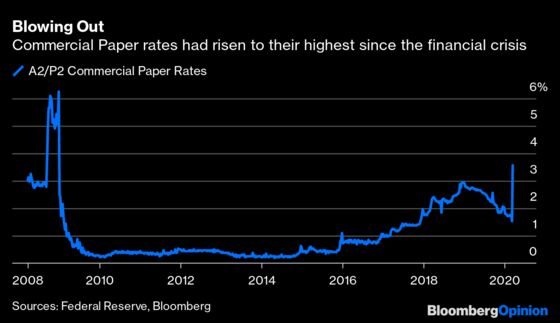

There was some relief on Tuesday after the Fed announced it will restart a financial crisis-era program to help U.S. companies borrow in the $1 trillion market for commercial paper, which are short-term IOUs generally ranging from about 15 days to nine months. This market is critical for companies looking to meet payroll and other short-term financing needs. Rates for commercial paper graded A2/P2, which is a step below the top tier, surged in recent weeks from less than 1.5% to more than 3.5% on Monday, threatening to put even more of a strain on the diminishing cash flow of companies. “We heard loud and clear there were liquidity issues,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin later told a press conference where the White House announced a series of measures to provide support to the economy. Working together with the Treasury, Mnuchin added that the Fed has the ability to “purchase up to $1 trillion dollars of commercial paper as needed.” On top of that, Bloomberg News reported that Mnuchin is seeking a new round of coronavirus-related economic stimulus totaling $1.2 trillion from Congress, and is discussing the idea of combining it with a relief package the House passed over the weekend. Nice, but what the U.S. probably needs is a $2 trillion asset-bailout program plus a massive loan program to provide consumer relief and to “salvage viable companies that are struggling,” Guggenheim Partners Global Chief Investment Officer Scott Minerd said Tuesday in a note to clients.

RIGHT FOR THE WRONG REASONS

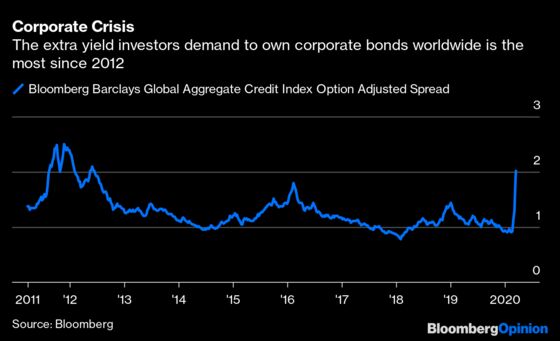

Back when the yield curve inverted in August, with yields on Treasury 10-year notes falling below those of two-year securities, there was a heated debate about whether the market was really forecasting recession or sending a false signal. After all, the stock market was soaring and companies were hiring, pushing the unemployment rate to a 50-year low. Well, there is no doubt now that the U.S. economy is either already in a recession or headed into one shortly. True, the coronavirus was on nobody’s radar screen in August, but the bond market may have been signaling that it wouldn’t take much of a shock to cause the economy to retrench, given how indebted companies had become. At almost $75 trillion, the mountain of global corporate debt excluding that of financial companies is about 93% of global gross domestic product, up from 75% prior to 2008 global financial crisis, according to the Institute of International Finance in Washington. “This crisis is aimed at corporate balance sheets,” Bob Michele, global head of fixed income at JPMorgan Asset Management, told Bloomberg TV.

IT WAS BAD ALREADY

Everyone knows that the economic data for March and the rest of the year is going to look pretty bad. But what few expected was how weak things were already. That became apparent Tuesday with the release of some less-than-encouraging data on retail sales and factory output in February for the U.S., the world’s largest economy. Purchases at the nation’s retailers slid 0.5%, the most since 2018, as sales declined in nine of 13 retail categories, Commerce Department figures showed Tuesday. Output at manufacturers barely rose as idled Boeing Co. 737 Max production continued to weigh on the industry, according to Bloomberg News’s Vince Golle, citing Fed data. The economists at Morgan Stanley say a worldwide recession is its “base case,” with global growth expected to fall to 0.9% this year. Those at Goldman Sachs predict growth of 1.25%, while S&P Global Ratings sees something between 1% and 1.5%. Painful, for sure, but not as bad as the 0.8% contraction of 2009, as measured by the International Monetary Fund. On the other hand, global growth in line with those forecasts would be worse than the downturns of 2001 and the early 1990s.

TEA LEAVES

Call it the last gasp for one of the strongest parts of the economy. Those looking at a long-term chart of U.S. housing starts wouldn’t be too bothered by January’s 3.6% drop from December’s pace of 1.626 million units, which was the most since 2006. Nor would they likely be flummoxed by the 4.3% drop that is forecast for February, which would bring the pace of starts down to 1.5 million, a level higher than anything seen since 2006 save for the prior two months. Those numbers will be released Wednesday. But it’s likely to be all downhill from there. Nobody will want to venture out and buy a house in this environment even with interest rates at record lows. Given how important the spring home-buying season is for the economy, a downturn would almost certainly weigh on growth.

DON’T MISS

Fed Used Its Bazooka. Now It’s Government’s Turn: William Dudley

Wall Street Panic Is Inside Heads of the Pros: Barry Ritholtz

The End of OPEC Is Here Thanks to Saudi Arabia: Julian Lee

Respond to the Coronavirus With All of the Above: Karl W. Smith

Big Business Is Helping U.S. Survive Coronavirus: Tyler Cowen

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.