Box Office Bends to Hollywood, Forever Changing Movie-Going

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- That sound you just heard is a window shattering, and Comcast Corp. billionaire Brian Roberts is holding the brick.

I’m talking about the theatrical window, that is — the period during which movies are available exclusively at cinemas before viewers can watch them at home. Instead of the standard time frame of 75 to 90 days, Comcast’s Universal Pictures is chopping it to 17 days as part of a game-changing agreement with AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc., the biggest theater operator in the world. AMC will get a slice of the on-demand fees, though the companies didn’t specify how much. It’s only a matter of time before other exhibitors are forced to strike similar pacts with Universal, and other studios are likely to try for the same.

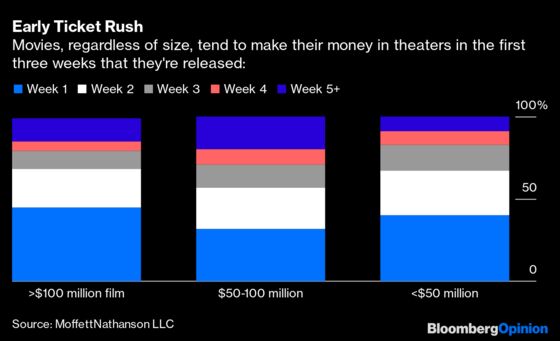

The good news is that consumers frightened to return to the close quarters of a cinema auditorium amid the Covid-19 pandemic won’t have to wait as long to rent movies from their TVs. And most box-office ticket sales come in the early days of a movie’s release anyway:

Even before the virus, people were visiting theaters less often, in large part thanks to Netflix Inc. constantly refreshing its library. In April, after U.S. lockdowns took effect, Universal’s “Trolls World Tour” made the controversial decision to skip theaters entirely and go directly online, generating almost $100 million in fees. That’s when simmering tensions with theater operators boiled over and AMC banished Universal films from its screens. Tuesday’s deal puts an end to that drama, for now. But as the ongoing threat of the coronavirus makes it harder for Hollywood to get back to work, consumers are running out of new stuff to watch. Even the fall TV season is up in the air. Meanwhile, studios are sitting on new films, just waiting for theaters to reopen and for a sign that enough fans will actually show up. The two big movies of the summer — “Tenet” from AT&T Inc.’s Warner Bros. and Walt Disney Co.’s “Mulan” — have been repeatedly pushed back.

If Universal and AMC’s agreement becomes commonplace, it will upend the theater industry. Operators will have to slash their number of locations and try to squeeze more concession-stand sales out of fewer patrons. That doesn’t mean theaters will disappear entirely anytime soon. In a worst-case (yet plausible) scenario, continued financial strain could eventually drive theater houses into the arms of Hollywood and technology giants that have a vested interest in keeping at least a diminutive version of the industry going.

Blockbuster films such as “Avengers: Endgame” from Disney’s Marvel last year — the highest-grossing film of all time with $2.8 billion in global ticket sales — still depend on the box office. Theater-goers in the U.S. pay an average of $9 per person (and in many cities much more), whereas a $20 on-demand rental is good for an entire household and not something most families will pay every weekend or even every month. And they can access a variety of movies and programs for a whole month on services such as Disney+ and HBO Max for less.

A shorter theatrical run may give smaller films a chance to lower marketing costs and make more money. It’s expensive for studios to promote films around a theatrical release and then have to drum up interest all over again to drive on-demand sales (or DVDs — remember those?) months later. Putting those dates closer together provides an incentive for more movies to get made and to be shown in theaters, rather than being sold directly to streaming-video services.

This could also be an opportunity for theaters to strike agreements with Netflix and other services producing original content, according to Michael Nathanson, an analyst with MoffettNathanson LLC. Those apps wouldn’t want their movies tied up in cinemas for two-and-a-half months, but two-and-a-half weeks is more palatable. “We think it could serve the interests of both exhibitors and Netflix to reach an agreement in order to help fill in any lost product directly from the major studios,” he wrote in a note to clients Wednesday.

Even if the economics prove better for some films this way and it eases industry tensions, the larger question remains: Will people ever return to theaters?

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tara Lachapelle is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the business of entertainment and telecommunications, as well as broader deals. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.