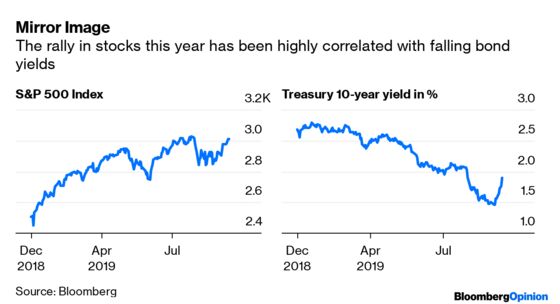

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- September is only halfway done and already the S&P 500 Index is up 20% for the year. This is a remarkable achievement, given that earnings growth has stalled and the bond market is pricing in almost a 40% chance of a recession over the next 12 months. That just shows the degree to which lower interest rates have supported stocks. And yet, as is often the case in life, too much of a good thing isn’t always, well, good.

This year’s rally – during which the S&P 500’s forward price-to-earnings multiple expanded to 17.6 from 14.5 at the start of January – can be credited to the Federal Reserve’s dovish pivot, which led to the central bank’s first rate cut since 2008 and sparked big declines in market rates. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note dropped to as low as 1.43% earlier this month from 2.80% back in January.

Simple discounted cash-flow analysis shows how lower rates make future earnings more valuable now, justifying higher multiples for equities even without profit growth. So, logic would dictate that the lower rates go, the better for equities. But the experience in Europe shows that there comes a point where ever lower rates begin to work against stocks.

In a research note last week, the strategists at Bank of America pointed out how even though 10-year bond yields in Germany have fallen below zero, stocks there only trade at a multiple of about 14 times earnings. That’s little changed from mid-2014, when yields were around 1.25% and the European Central Bank cut its benchmark deposit rate to below zero. The same is true for the broader euro zone, with the Euro Stoxx 600 Index trading at 14.5 times projected earnings, not much different from mid-2014.

Of course, the euro zone’s struggles are worse than the U.S. Still, the increasing globalization of the world economy means America is having a much harder time shrugging off the slowdown elsewhere. Morgan Stanley says the U.S.’s share of global gross domestic product has shrunk from 22% in 1990 to 15% today. That’s a big reason traders are pricing in at least three more Fed rate cuts over the next 12 months, bringing its target rate for overnight loans between banks to 1.50% from 2.25% currently.

On top of that, the number of Wall Street strategists slashing their Treasury yield estimates has grown in recent weeks, citing the outlook for weaker global growth and inflation. UBS Group AG and BNP Paribas SA, which are among the select group of dealers authorized to trade with the Fed, both slashed their 10-year forecasts, predicting yields will drop to 1% by the end of 2019. Could yields go even lower, tracking those in Europe and Japan by following below zero? Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan doesn’t thing that’s a crazy idea, telling Bloomberg News last month that he wouldn’t be surprised if they turned negative.

It’s true that the stock market posted a massive rally between early 2009 and mid-2015, rising as much as 215%, as the Fed kept rates near zero and pumped money directly into the financial system via quantitative easing. But that was a time when investors largely believed that central banks still had a lot of arrows left in their quivers to stimulate the economy. That’s not really the case now. The S&P 500 fell four straight days after the Fed cut rates on July 31, dropping a total of 5.59%.

Also back then, profits were in recovery mode and stocks were relative cheap, with the forward price-to-earnings ratio holding below 14 for much of that time and peaking at around 17 times in late 2014 – about where it is now - just before the S&P 500 turned in its first annual decline since 2008. This year, though, earnings growth is flat and Bank of America’s strategists are telling its clients that forecasts for an 11% increase next year are “too high.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.