The Oil Price Rally Is Bad. The Diesel Crisis Is Far Worse

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Winston Churchill famously referred to Russia in 1939 as a series of layers: a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. Very much like a matryoshka doll. The oil market of 2022 is a bit similar: a tight crude market, wrapping an even scarcer oil feedstock market, enclosing a diesel market in crisis mode.

Oil benchmarks Brent and West Texas Intermediate tend to grab the attention of financial markets. However, regular consumers — households and businesses — don’t buy crude; they purchase refined petroleum products such as diesel and gasoline. Now, there isn’t much diesel to buy.

That’s a big problem. Diesel is the workhorse of the global economy. It keeps trucks and vans, excavators and heavy machinery, freight trains and ships all buzzing. Wholesale and retail diesel prices surged last week to an all-time high, surpassing the peak set in 2008.

In the U.S., average retail prices have surged above $5 per gallon for the first time ever. In the U.K., it’s selling above 1.70 pounds per liter, equal to more than $8.5 per gallon. The surge matters because of the ubiquity of diesel in modern life. As the fuel of transportation, the price rally will hit everyone, adding to inflationary pressures that are already running at a multi-decade high. More than the cost of oil, skyrocketing diesel prices should be the main worry of central banks.

The dire diesel supply situation predates the Russian invasion of Ukraine. While global oil demand hasn’t yet reached its pre-pandemic level, global diesel consumption surged to a fresh all-time high in the fourth quarter of 2021. The boom reflects the lopsided Covid economic recovery, with transportation demand spiking to ease supply-chain messes.

European refineries have struggled to match this revival in demand. One key reason is pricey natural gas. Refineries use gas to produce hydrogen, which they then use to remove sulphur from diesel. The spike in gas prices in late 2021 made that process prohibitively expensive, cutting diesel output.

Low-sulphur crude is also in short supply: OPEC+ countries that pump that kind of oil, such as Nigeria and Angola, are unable to increase output. Any additional production has to come from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, but both largely produce crude with high sulphur content.

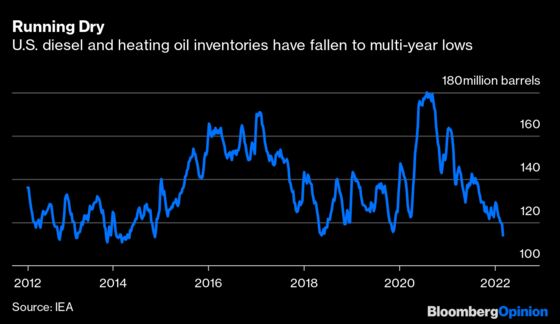

Ever before the war, diesel inventories had fallen to perilously low levels, particularly in the U.S. and the European oil hub of Antwerp, Rotterdam and Amsterdam (ARA). In the U.S., diesel stocks fell last week to their lowest seasonal level in 16 years. In the ARA region, they are at a 14-year seasonal low.

Now the conflict in Ukraine is making a bad situation a lot worse. Europe is the largest diesel deficit region in the world, relying on Russian supply to plug the hole. Of the nearly 1.4 million barrels a day of diesel Europe imported in 2019, about half, or 685,000 barrels, came from the former Soviet Union. Another 285,000 barrels came from Saudi Arabia. Europe is also a global pricing hub for diesel, so whatever happens in Europe reverberates around the world.

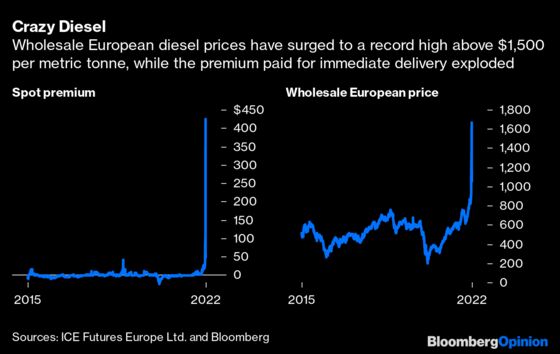

The loss of Russian supplies is particularly acute for northern Germany, which receives seaborne Russian cargos directly via Hamburg and other ports. In a reflection of the crisis, benchmark wholesale European diesel prices hit a new high last week. The premium for diesel for immediate delivery exploded — at one point, it was 100 times more than usual — in a sign of extreme tightness.

The situation is made worse because Europe doesn’t just import finished diesel from Russia, but also semi-processed oil that it further refines to make diesel. The lack of that feedstock, including vacuum gas-oil and straight run fuel-oil, is forcing some refiners to cut supplies. Both Shell Plc and OMV AG have started to restrict their wholesale supplies. OilX, a consultant, has told clients it sees “a real risk of physical shortages of diesel in Europe.” Privately, oil traders and oil companies say the same. No one wants to raise the alarm, fearing a run on gas stations, but everyone is quite worried.

If nothing changes, by early April, some European countries may need to restrict diesel sales to conserve supplies.

China, a major diesel exporter that could come to the rescue, is instead cutting its overseas sales to save fuel at home. Even Saudi Arabia, a major diesel supplier to Europe, is now buying rather than selling.

Europe faces another problem, too. The region accounts for about one-third of global biodiesel production. But with Ukrainian vegetable oil exports virtually stopped because of the Russian invasion, the price of rapeseed oil — a key ingredient of biodiesel — has surged, putting European production at risk at the worst possible time.

Europe and the U.S. have some tools to cope. Beyond their strategic oil reserves, both have reserves of diesel and heating oil that they can release into the market to alleviate shortages. In Europe, governments should be proactive. Last year, the British government was too slow in responding to a shortage of fuel, and by the time it reacted, it was too late.

Western policymakers are glued to the screens showing the price of oil — they should focus instead on diesel. If anything is going to break soon in the petroleum market, diesel is the most likely candidate.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of "The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources."

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.