Steel Is the Other Big Commodity Shock from the War in Ukraine

Europe needs to wake up to the nascent steel crisis. Price spikes and potential shortages could ripple across the global economy.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Joseph Stalin ordered the construction of the Iron & Steel Works in Mariupol in 1930 — one of his mega-projects to industrialize the Soviet Union. For a time, the complex was one of the world’s largest steel mills. Nearly a century later, another Russian leader with a Stalinist bent, Vladimir Putin, ordered its destruction.

The bombs falling on the blast furnaces of Mariupol, the Ukrainian city under Russian siege, are a symbol of how the war has turned the steel market upside down.

The world is fixated on the war’s impact on global energy markets. The surge in oil prices have dominated the headlines. But alongside oil, steel is a foundation of the modern economy. The ubiquitous commodity underpins the world as we know it, a key material in everything from skyscrapers and cars to washing machines and railways.

Now Russia’s invasion threatens to turn steel into a luxury commodity. Prices have surged, and the rally will be felt everywhere, adding to global inflationary pressures.

Consider the average car: About 60% of its weight comes from steel, according to trade body the World Steel Association. In cash terms, the cost of that steel has gone up to more than 1,250 euros ($1,379) from about 400 euros in early 2019.

For central banks, the steel price boom is another inflation headache. Meanwhile, European governments may have to grapple with both price increases and the threat of potential shortages this summer. Rebar steel, the long and corrugated rods used to reinforce concrete in every construction project, may be in limited supply soon.

The European Union has already imposed sanctions on some Russian steel sales and has targeted most of the country’s oligarchs who own large chunks of the Russian steel industry. And the war has all but stopped Ukrainian steel production.

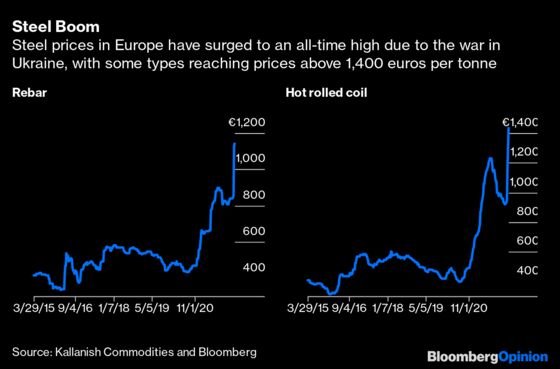

The cost of rebar steel in Europe last week surged to a record of 1,140 euros per tonne, up 150% from late 2019. And the price of hot-rolled coil, a popular form of steel, has reached a record high of about 1,400 euros per tonne, up nearly 250% from just before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

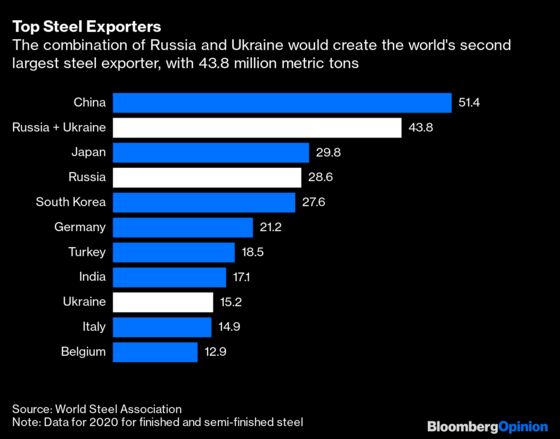

One reason for the price spike is the sheer size of the Russian and Ukrainian steel industries. Russia is the world’s third biggest steel exporter, behind only China and Japan, while Ukraine is the eighth largest.

Colin Richardson, head of steel at Argus, a price reporting agency, reckons that Russia and Ukraine together account for about a third of the EU’s steel imports, or nearly 10% of the region’s domestic demand. And Russia, Belarus and Ukraine together account for about 60% of total EU imports of rebar. They also have a huge share of the market for slab — the chunky pieces of semi-finished steel.

Rising prices are also being driven by the war’s impact on energy prices and the steel industry outside Russia.

Although steel is associated with huge blast furnaces like the ones destroyed in Mariupol, in Europe about 40% of the metal comes instead from so-called electric arc furnaces or mini-mills. Rather than iron and coal, the mini-mills use huge amounts of electricity to melt iron scrap into fresh steel. Mini-mills are more environmentally friendly, but their Achilles heel is power consumption. And right now, Europe is short of energy.

With the war sending gas prices higher, European short-term power prices have also surged, peaking earlier this month above 500 euros per megawatt hour, or about ten times higher than before the crisis. The price jump forced many mini-mills from Spain to Germany to shut down or reduce output, running at full capacity only at night when electricity is cheaper.

The closures are further tightening the European market, prompting some users to fear not just high prices but perhaps even shortages. Steel executives are worried that prices may rise sharply higher, perhaps by another 40% to around 2,000 euros per tonne, before demand slows down. Speaking in private, industry executives say that if electricity prices surge again and more European mini-mills close, the prospect of actual shortages for rebar steel is real. Panic buying may inflate prices, too.

Brussels and London need to wake up to the crisis. If the global economy has learned anything during the Covid pandemic, it’s that supply-chain issues spread faster than expected and also have a deeper impact than anticipated. And there are few commodities so crucial to so many industries as steel.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of "The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources."

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.