Uber Waited Too Long to Go Public. Take Note, Unicorns.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Uber Technologies Inc.’s botched market debut has a lesson for other unicorns: Don’t wait so long to go public.

Companies have more access to private capital than ever before, and many are putting off the scrutiny of public markets for as long as possible. There are 349 unicorns, or private companies valued at $1 billion or more, around the world, according to research firm CB Insights. By avoiding public markets, those unicorns are forgoing critical feedback about their progress — feedback that fawning private investors are unlikely to provide and that Uber could have used sooner. Changes are easier when a company is smaller and more nimble.

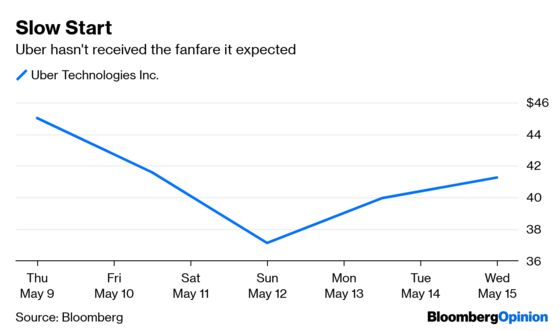

Instead, Uber learned only in recent days that the market isn’t as enamored with it as it believed. Morgan Stanley, the lead underwriter in Uber’s initial public offering, suggested last year that the ride-hailing company could be worth as much as $120 billion. By that yardstick, Uber must have viewed the $75.5 billion valuation at its IPO as a fire sale, but it turns out the market thinks it’s worth even less. The stock is down 8.4 percent since Friday’s IPO through Wednesday, bringing its market value to $69 billion.

In December 2014, questions arose about Uber’s process for screening drivers after a passenger in India accused one of rape. In June 2015, taxi drivers and their supporters protested across France, blocking roads and attacking suspected Uber drivers — a preview of protests that erupted later in other countries. That same month, the California Labor Commission ruled that Uber drivers were employees, not independent contractors, challenging the company’s business model.

Then came questions about Uber’s integrity. In July 2016, a federal judge found that Uber “engaged in fraudulent and arguably criminal conduct” when it hired an investigator to snoop on a plaintiff in a lawsuit. In February 2017, a former Uber engineer publicly complained about a toxic and sexist environment at the company, and the New York Times described it as “an aggressive, unrestrained workplace culture.” That same month, Waymo, the self-driving car company, contended that Uber stole its trade secrets. (Uber settled the case for $245 million.) And in November 2017, Bloomberg News reported that Uber paid hackers $100,000 to cover up a data breach affecting 57 million customers and drivers a year earlier. (The company ousted its chief security officer and one of his deputies.)

It’s hard to imagine that a public company’s market value could continue to climb without significant attempts to address its most serious problems, but staying private allowed Uber to do just that. It’s a good thing, some would say, but that’s misguided. The bigger a company grows, the harder it is to change the culture or address core business issues. Also, if Uber had been exposed to the rigors of public life sooner, it probably would have been more careful.

To its credit, Uber has taken some steps to clean up its culture, but the big questions remain, as the market appears to be reminding it. In a memo released Tuesday, the National Labor Relations Board concluded that Uber drivers are contractors, not employees, but is it realistic that drivers will continue to work for a pittance without the protections and benefits afforded employees, such as health care and retirement plans? Can Uber continue to take business from taxi drivers without more pushback, or regulation that would impose similar standards on Uber drivers as on taxi drivers? And can Uber continue to rely on the goodwill of drivers and riders without doing more to ensure their safety?

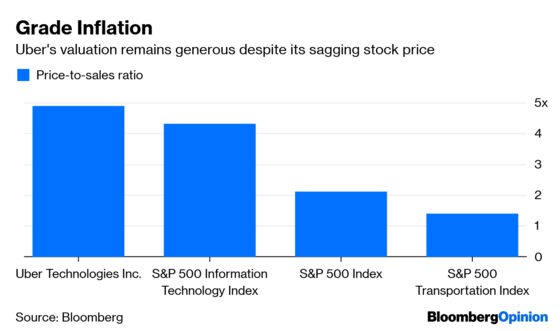

Uber no doubt believes the market is being too hard on it, but the numbers suggest otherwise. Its price-to-sales ratio is 4.9, based on analysts’ revenue forecast for 2019. That’s 15 percent higher than the S&P 500 Information Technology Index, the richest sector by that measure, 138 percent more expensive than the S&P 500 Index, which is no bargain, and 252 percent higher than the S&P 500 Transportation Index. In other words, Uber’s stock could get a lot cheaper.

Judging by its reaction so far, it’s not clear that Uber has received the message. Rather than acknowledge that the company’s private valuation may have been too generous, CEO Dara Khosrowshahi blamed Uber’s sagging stock price on the broader environment, saying in a letter to employees, “Obviously our stock did not trade as well as we had hoped post-IPO. Today is another tough day in the market, and I expect the same as it relates to our stock.”

None of this means Uber won’t overcome its challenges. But the deep disconnect between the company and the market suggests that Uber was scarcely aware of the skepticism that awaited, a reality it would have done better to understand and address sooner. It’s a lesson the other unicorns safely nestled in the enchanted forest should note.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.