OPEC Is Holed Below the Waterline, It Just Doesn’t Know It Yet

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It doesn’t seem much, but the most damaging leaks often don’t. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries has suffered a small crack that could grow to into a rift big enough to sink it.

No, I’m not talking about the bust-up between Saudi Arabia and arch-rival Iran, nor wrangling over Iraq’s repeated failure to abide by its output target under the current production deal. Rather, I’m referring to a decision by the United Arab Emirates, the group’s third biggest producer, to allow its crude to be traded freely on the open market by its initial buyer. That’s an initiative that veteran oil analyst Philip K. Verleger says eventually “could weaken OPEC and the [OPEC+] Coalition.”

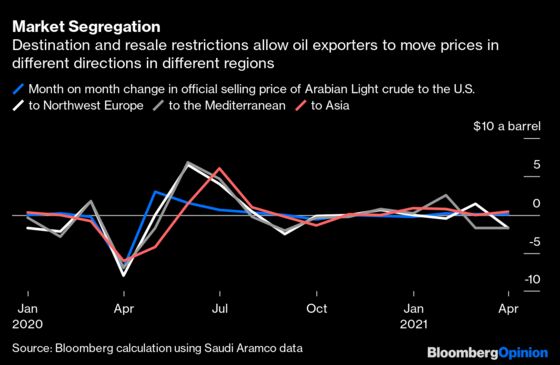

Until now, the big OPEC producers of the Persian Gulf — Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait and the UAE — have sold their crude under strict terms that dictate where it can be delivered and prevent its resale by the original lifter. That has given them the ability to vary the prices they charge in different parts of the world, depending on local market conditions, and maximize their revenues. A buyer’s failure to adhere to these terms has meant it could be shut out of future purchases.

By removing those conditions, the UAE is relinquishing that ability, making it possible for its crude to be diverted by the buyer from one region to another if it becomes more profitable to do so. It may also open up the Persian Gulf crude market to the big oil trading companies like Vitol Group, Glencore Plc and Trafigura Group. The increased flexibility and bigger pool of potential buyers will improve the appeal of the UAE’s crudes over those of its less flexible neighbors.

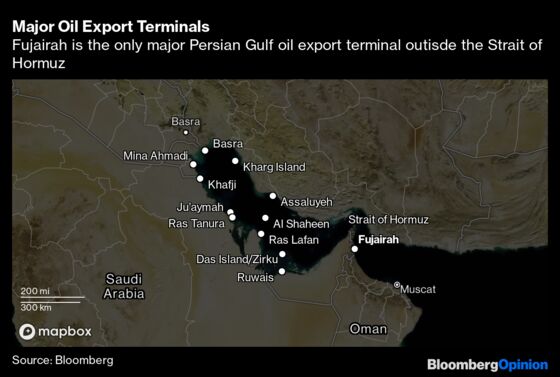

That’s an advantage that will be amplified by the ability to load the country’s key Murban export grade at Fujairah, which is located outside the sensitive waterway of the Strait of Hormuz, a selling point that its Persian Gulf rivals mostly lack.

It’s the first time such an exception has been made. Iraq offered destination-free exports for a limited volume of its crude under a pre-payment contract that it awarded to China ZhenHua Oil Co. in December. But that agreement never came into effect and the deal was scrapped by the Iraqis last month, after the rise in oil prices alleviated some of their immediate revenue needs.

The dropping of destination and resale restrictions was only the latest move by the UAE suggesting that it’s starting to take a different line from its OPEC fellows.

The country clashed with its partners over easing output restrictions when they met at the end of November, forcing the discussions into a second day and thereby delaying a meeting with their non-OPEC allies to agree a small production increase for January. The UAE insisted that any decision to lift the output target had to be accompanied by strict undertakings from those OPEC+ members that had failed to comply with their targets to make up for any excess production in the months that followed.

That insistence appeared to be driven by frustration with how it was treated when it over-produced briefly last summer. Energy Minister Suhail Al-Mazrouei was summoned to Riyadh for a public dressing down, while Russia — which has consistently pumped above its target — has faced no criticism at all.

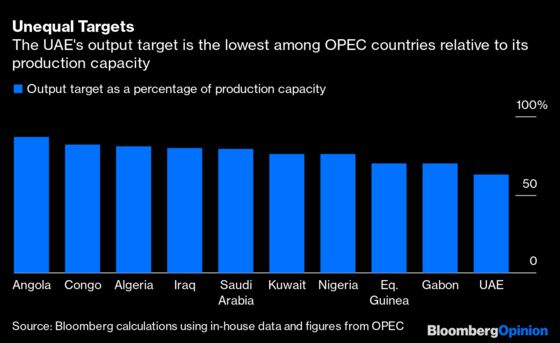

The UAE also regards the restrictions on its production as tougher than those imposed on others. At 2.63 million barrels a day, its target is just 63% of its capacity to pump crude out of the ground. That compares with 79% for Saudi Arabia. Even the kingdom’s unilateral additional cut doesn’t bring its shut-in production to the UAE’s level.

The difference with its neighbor over oil policy is just one small fissure in a network of cracks that includes the UAE reducing its involvement in the Saudi-led war in Yemen and Riyadh unilaterally breaking the embargo of Qatar, forcing the Emiratis to follow suit.

The changes to its oil contracts are part of a drive to establish Abu Dhabi’s Murban crude as a regional benchmark for Middle East oil sales to Asia, the region’s most important market. That would give a boost to efforts by Abu Dhabi, the largest of the emirates and holder of most of the UAE’s crude reserves, to position itself as an oil-trading hub, rather than just an exporter.

It is eager to utilize more of its production capacity, which it intends to boost by almost 20% to 5 million barrels a day by 2030, before oil demand starts to wane as the world increasingly turns away from fossil fuels. That could be putting it on a collision course with the rest of OPEC.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg. Previously he worked as a senior analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.