(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s now clear in hindsight that a global pandemic was one of those things that financial markets never truly considered a real threat. This raises the question of what other so-called black swans might be lurking out there? Here’s one that might happen sooner rather the later: a failed auction of government bonds by the U.S. Treasury Department.

Such a notion was unthinkable just a few months ago for the world’s richest economy and one that enjoys the exorbitant privilege of controlling the world’s primary reserve currency. Sure, the chances are still negligible that the government won’t find enough buyers for all the bonds it needs to sell to finance an estimated $3.7 trillion budget deficit. But the point is that the odds, however slim, are probably no longer zero, and if they are not zero, then markets need to start discounting such a catastrophic scenario.

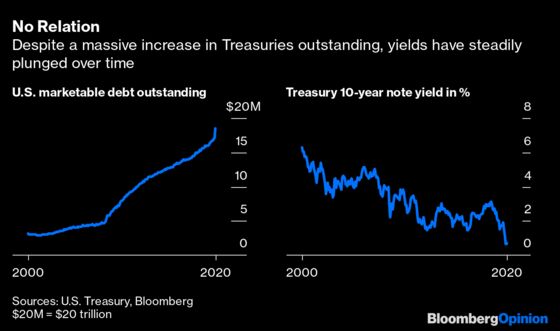

The reason why is that the U.S. Treasury is starting to auction $3 trillion in the span of a few months. No country at any time has every attempted such an audacious borrowing plan. Consider that the U.S. issued about $1 trillion in bills, notes and bonds in all of 2019. Simple laws of supply and demand suggest that when there’s an abundance of something, the price of that thing falls. The bond market seems to have been the exception, with yields – which move inversely to bond prices - having steadily declined to next to nothing despite the amount of U.S. marketable government debt outstanding having risen to $18.5 trillion from less than $5 trillion before the financial crisis.

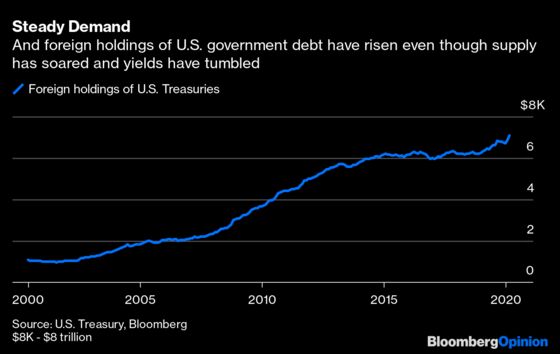

But are we finally at the point where supply overwhelms demand? On the plus side, demand has held up at recent auctions despite record-low yields. Of course, those yields are still positive, which is appealing in a world with $11 trillion of debt carrying negative yields, including in Germany, Japan and most other major economies. And the dollar has been strong, so foreign investors have been happy to buy U.S. debt and benefit by holding assets in an appreciating currency.

Still, we simply do not know what will happen with such large auctions. Even if there is enough demand to absorb all the extra supply (and the primary dealer system all but prevents a failed auction) there’s the very real possibility that at the least investors will demand sharply higher yields to compensate for the deluge of debt. Higher yields will then result in increased borrowing cost for companies and consumers, providing an obstacle to the economic recovery.

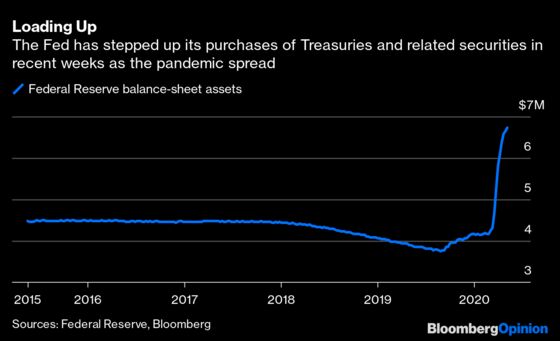

But if demand seriously wanes, and there simply aren’t enough bidders to participate in the auction, the expectation will be that the Federal Reserve will step in as the buyer of last resort, and participate in bond auctions as a direct bidder. This would have both political and economic significance, for it would be signal the direct monetization of debt. Every time in history that a central bank has directly financed its federal government, the result has been disastrous, usually resulting in lots of inflation with the most famous example being Germany in the 1920s.

In the meantime, the Fed has been indirectly monetizing government debt by purchasing Treasuries and related securities in the secondary market, pushing its balance-sheet assets to $6.72 trillion from about $4 trillion just a couple of months ago and less than $1 trillion just before the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

The difference is not simply philosophical. If the Fed buys debt directly from the Treasury, it would be because the U.S. government has failed to sell its debt at auction and is simply unable to finance itself. The government would then be faced with a stark choice: allow the monetization of debt and risk the potential for runaway inflation, or impose spending constraints that devastate the economy. Up until this point, the government hasn’t faced these trade-offs. It borrowed more and more, and interest rates went down anyway.

By definition, one cannot predict a black swan event, but they always seem to be obvious in hindsight. As we have seen the last few months, the bond market is fragile, and has occasionally ceased functioning properly. When brainstorming about possible black swans, it is important to think about vulnerability. They always seem to find that point of vulnerability, like what happened with oil prices last month, and what happened to the economy under Covid-19.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jared Dillian is the editor and publisher of The Daily Dirtnap, investment strategist at Mauldin Economics, and the author of "Street Freak" and "All the Evil of This World." He may have a stake in the areas he writes about.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.