(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In pre-Covid times, arguably the most crucial component of the Labor Department’s monthly payrolls report for bond traders was growth in average hourly earnings. After all, higher wages suggest a tighter U.S. job market and the prospect of inflationary pressure building in the world’s largest economy.

The Covid-19 pandemic and its disparate impact on certain industries seemed to render wage data irrelevant. For instance, average hourly earnings jumped 8.2% in April 2020 relative to a year earlier, far and away the sharpest increase on record. But that was because lower-paid service workers lost their jobs and dropped out of the calculation. In last week’s report, which most analysts considered strong across the board, average hourly earnings declined month-over-month for the first time since June. With so many workers displaced and local economies reopening at different speeds, it’s difficult to get a good read from these figures.

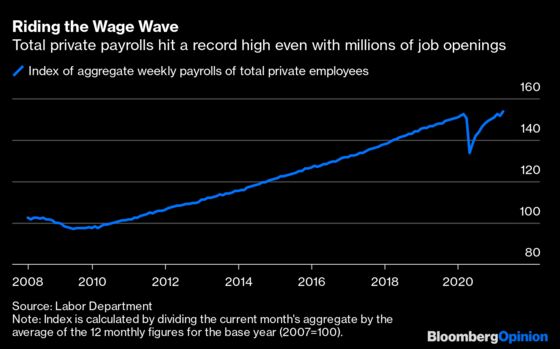

Or perhaps it only requires looking at a more comprehensive calculation. Tom Porcelli and Jacob Oubina at RBC Capital Markets flagged what’s known as the index of aggregate weekly payrolls, which they argue shows a fuller picture of the overall “wage pie” because it effectively incorporates average hourly earnings, average weekly hours worked and employment. By this measure, which Porcelli has favored for years, private sector workers are now taking home more money than they were as a group in February 2020, just before the onset of the pandemic.

This kind of fully formed V-shape might be commonplace when looking at stock market indexes, but it’s rather rare in the world of U.S. labor market data, which tends to show the recovery is woefully incomplete. Examples include the employment-to-population ratio and the labor force participation rate:

To be clear, the index of aggregate weekly payrolls doesn’t suggest the U.S. is anywhere close to the Federal Reserve’s vision of full employment. For one, it takes only a quick eyeballing of the data to see it remains below where it would have been had the previous pace of wage growth and employment continued linearly. Chair Jerome Powell has made clear that the central bank won’t declare victory until many more Americans return to the labor force, including those who took longer to find jobs during the last recovery. Its “broad-based and inclusive” criteria is why Wall Street economists are now trying to forecast new variables that could influence the Fed, such as the Black unemployment rate.

However, the fact that overall private wages are higher than ever, even with the U.S. economy down some 9 million jobs, seems to raise the risk that inflation could be stronger than policy makers anticipate. “As jobs continue to come back, all in the context of businesses that are right now saying labor markets are tight, these wage pressures will only grow, thus adding momentum to an inflationary dynamic that is primed to rise from here,” Porcelli and Oubina wrote. “In combination with a big demand push, supply challenges and a consumer that has the means to keep demand elevated, we think the coming year is likely to come as a surprise to a Fed that we think is underappreciating just how much inflationary pressure is out there.”

In the latest sign of this dynamic, the Labor Department on Tuesday released its February Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, which showed available positions in the U.S. reached a two-year high of 7.37 million. Yet businesses have said they’re struggling to find workers for these positions because of pandemic-related issues such as child care and health concerns, which could partly explain why joblessness deemed “permanent” remains so stubbornly high. If companies have a sense of urgency in filling those openings, they’ll likely have to pay up. And if labor costs are rising, it stands to reason that executives will look to boost prices to avoid entirely shouldering that burden.

Persistent wage pressure creates a potentially more enduring inflationary cycle than simply counting on pent-up savings from the past year creating overwhelming demand. I joked around when Powell said last month that “you can only go out to dinner once per night,” but the sentiment about having finite time to eat at restaurants, go to movie theaters and stay at hotels rings true. New York Fed researchers argued this week in a blog post that the estimated $1.6 trillion in excess savings aren’t really that excessive and that while the U.S. economy may strongly recover from the pandemic, “spending out of excess savings won’t be one of its major drivers.”

All this is to say, as the U.S. enters a new economic era, it might be time to start scrutinizing wage data again. The numbers indicate that the overall decline in private workers’ income was remarkably short-lived — it took almost three years for a similar rebound after 2008. If this pace continues for the rest of the year, policy makers could very well reach their inflation targets sooner than expected, even if their labor-market goals remain a ways away.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.