U.S. Can Punish Russia Even More in the Bond Market

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- With Vladimir Putin’s Russia mustering troops along the border with Ukraine, it’s time again to make clear to Moscow that the West is not toothless. The U.S. is uniquely positioned to counteract Russian aggression — or that of any other adversary — by financial proxy thanks to the global dominance of the dollar. Acting in concert with the European Union and the G-20 could make any penalties all the more powerful.

Speculation is mounting about what the U.S. and its allies might do, including cutting off Russia from the Swift payment system, which executes transactions among banks worldwide. But that measure — deemed a “nuclear option” by some — risks harming many Russian citizens and non-Russian institutions as well. There’s a simpler solution: More severely shut down the government’s access to global capital markets, which wouldn’t directly affect the populace but would certainly squeeze the ruling elite.

This has been threatened before, but ultimately American leaders opted for a more watered-down approach. In April, the Biden administration tightened up the sanctions, which restrict U.S. financial institutions from participating in the primary market for Russian sovereign bond deals.

“This reflects the delicate balance that President Biden and earlier administrations have attempted to strike by imposing meaningful consequences on large, globally significant actors without at the same time roiling global markets or imposing unpalatable collateral consequences on U.S. allies,” the executive order said. “Such a seemingly narrow expansion of restricted activities also leaves room to further strengthen measures if the Kremlin’s malign activities continue.”

Indeed, the U.S. could ratchet up the pressure on Moscow by also barring investors from buying Russian debt (ruble or non-ruble) in the secondary market. In fact, the executive order makes clear that it’s a loophole the Biden administration is well aware it could close if necessary, preferably in conjunction with its allies:

“The Directive also does not prohibit U.S. financial institutions from participating in the secondary market for Russian sovereign bonds — a potentially wide loophole under which U.S. banks may continue to purchase such debt, just not directly from the three targeted entities. This is a loophole that could be significantly closed if the United Kingdom and European Union adopted similar measures — further supporting our assessment that the administration designed these restrictions in part to be imposed alongside similar restrictions promulgated by London and Brussels.”

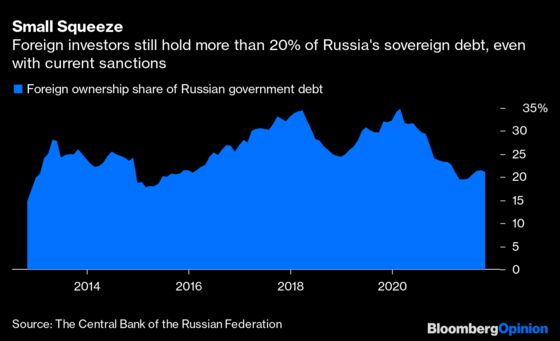

An escalation like this would have much bigger consequences for the Russian government than the current restrictions. As it stands, the foreign ownership of Russia’s sovereign debt has gradually diminished from about 34% at the start of 2020 to 21.2% as of October, according to data from Russia’s central bank. There hasn’t been a wholesale liquidation because the secondary market for the country’s securities is still wide open.

Meanwhile, Russia’s interest expenses have remained moderate, even though the intention of current bond-market sanctions was “penalizing the Kremlin by driving up its borrowing costs.” The government has been an active issuer of eurobonds in euros in recent years, with a 1 billion euro ($1.1 billion) 15-year issue as recently as May with a coupon of 2.65%. Clearly, this is a hugely important source of cheap, large-scale and longer-term funding for Putin’s regime. The list of registered holders includes the great and good of European and U.S. investment managers.

It’s far from clear who would be the buyer of last resort if these securities became part of a stronger sanction list, causing a serious dislocation and likely making it much more costly to borrow money. Domestic Russian institutions could probably swallow the sudden influx of sellers if foreigners were suddenly required to exit ruble-denominated government debt — but it wouldn’t be pretty.

As was made clear by the earlier directives, it’s important to keep some of these stringent powers in reserve. But other recent non-ruble issuers include large Russian banks raising perpetual debt, resource companies such as Lukoil and MMC Norilsk Nickel and even the State Transport Leasing Co. The U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control’s “Fifty Percent Rule” doesn’t apply to Russia, meaning that U.S. investors can still participate in the primary market for these bond offerings. If the list of sectors and companies sanctioned was widened — and especially if it also broadly restricted secondary-market transactions — that sudden lack of foreign capital would be calamitous for the Russian economy.

The U.S. needs to have the power to squeeze Russia’s access to funding and raise its borrowing costs — but just as important, be able to relax penalties as well. Sanctions up to now have been carefully targeted and less ferocious in reality than initially feared. That might need to change as the evidence so far suggests that the pain has been nowhere near sufficient to alter Moscow’s thinking.

More from other writers at Bloomberg Opinion:

- Ukraine Crisis Helps Doom Biden’s ‘Pivot to Asia’: Hal Brands

- How the West Can Prevent a Russian War in Ukraine: Editorial

- Putin Needs a Casus Belli to Invade Ukraine: Leonid Bershidsky

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.