U.S. 10-Year Yield Breaks 1% on Highway to Zero

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Bond traders have long been prepared to live in a world with lower-for-longer interest rates.

But this low? And this soon?

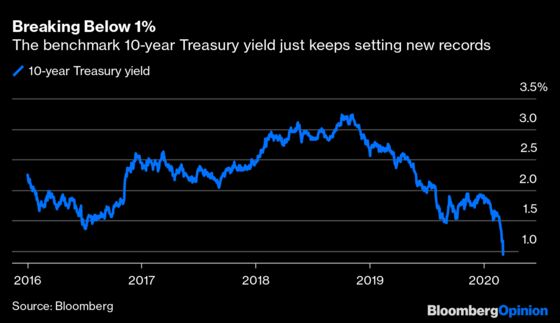

In nothing short of a historic day for the $16.7 trillion U.S. Treasuries market, the benchmark 10-year yield fell below 1% for the first time ever on Tuesday. The yield, which peaked at 15.84% in 1981 and more recently at 3.26% in October 2018, has tumbled just about every day in recent weeks. Mounting fear over the spreading coronavirus has forced investors to come to grips what what a pandemic might mean for the longest U.S. economic expansion on record.

One thing’s for sure: The Federal Reserve isn’t about to let the American economy falter without a fight. The central bank slashed interest rates by 50 basis points on Tuesday in the first inter-meeting policy easing since 2008. Now with the fed funds rate at 1% to 1.25%, Wall Street strategists say further reductions are not a matter of if, but when. Many see at least another 50 basis points by mid-year, mirroring expectations in the fed funds futures market. JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s Jan Loeys went even further, arguing that Treasuries are now trapped in negative-yield “quicksand” that will pull yields toward zero as soon as this year.

That’s a scary proposition. In a world with some $14 trillion in negative-yielding debt, U.S. Treasuries have long been seen as an alluring safe haven for long-term investors to at least lock in some positive yield, however small.

The idea that Treasuries will soon approach the zero bound has undoubtedly fueled the seemingly insatiable bid over the past two weeks, even as yields reached record low after record low. Just on Tuesday, the 10-year yield fell more than 25 basis points, to as low as 0.9043%, while two-year yields tumbled as much as 28 basis points. The yield on 30-year Treasury inflation protected securities — often referred to as a “real yield” — fell below zero for the first time ever.

“This is happening much faster than I thought as a result of large investors such as banks and insurance companies recognizing this and positioning now for falling bond yields — they’re doing heavy buying,” JPMorgan’s Loeys told Bloomberg News’s Vivien Lou Chen. “The thought is, ‘Whatever happens to the U.S. economy, we are ultimately going to zero yields and so buy more.’”

It’s hard to imagine that Treasury yields can continue to fall as fast as the past couple of weeks. But it’s even more difficult to envision a scenario in which they would rise in any meaningful or lasting way. Bloomberg News published an article Tuesday with the headline “Hottest Bond Market in History Is Starting to Make Some Nervous.” All the money managers quoted make valid points. But is it scarier to buy 10-year Treasuries that yield 1% or confront the potential scenario down the road in which yields are near-zero and regret not acting now? As I wrote on Jan. 27, plenty of investors hated the idea of Treasuries at 1.6% — but buying at that level would have netted a tidy 5% profit already.

Speaking of those profiting from the huge rally in U.S. Treasuries, I caught up with Lacy Hunt, who helps oversee the Wasatch-Hoisington U.S. Treasury Fund, in the minutes after the 10-year yield fell below 1% for the first time ever. His fund invests solely in long-dated Treasuries and has returned a staggering 40% over the past year and 17% in 2020 alone. That doesn’t even include today’s massive move.

If there’s any one person to hear from to on a day like this, it’s Hunt. He insisted for years, even when the Fed was tightening monetary policy, that “the secular low in long-term Treasury bond yields is well ahead of us, it’s not behind us.” He was absolutely correct.

Here are some of the highlights from our conversation:

“We came into the year thinking that the U.S. and global economy were weakening for a variety of reasons, we have too much of the wrong type of debt. We felt that in spite of the three cuts in the federal funds rate late last year and the Fed’s balance sheet expansion and the increase in money supply late last year, monetary policy was still restrictive based on the longer term money supply and bank credit trends.

…

If the chairman of the Federal Reserve is right, that we’re looking at an extended period of difficulty here, the historical record shows even if we have the mildest of recessions, the inflation rate is going to come down between 200 and 400 basis points.

Well, the core inflation rate is currently running about 1.5%. Which means you’re going to take core inflation into deflation.

…

Poor economic performance will cause the continuation of the decline in the real rate, and then the inflationary expectations will also fall. So we’re dealing with a very fundamental situation here.

When the short rates start coming down toward zero, even before they get to zero, you reach a reversal point and the counterproductive effects of the lower rates offset the beneficial effects of having a lower cost of borrowing.

…

My feeling is if and when they get it under control, and we all hope they will quickly, the recovery will not be V-shaped. It will be very shallow and difficult. And I think there’s ample reason for that. Since 2009, in major economic areas, we’ve had five recessions. Three in Japan, two in Europe. It may be that Europe and Japan are in their third and fourth recession, respectively. In each of those prior five cases, what did the conventional wisdom say about the recoveries? That they’d be V-shaped. But none of them were. This recovery is not going to be V-shaped because the economy was very fragile with all kinds of problems, and then this unfortunate set of circumstances hit.”

No one can truly know when or how this ends. Fear is palpable and central bankers are standing ready to do what they can to mitigate the harm to the economy. That means coordinated interest-rate reductions and persistent asset-purchase programs.

The damage is already done to traders’ psyches, however. The world’s deepest and most liquid bond market has crossed the Rubicon. America may not join the negative-yield club immediately, but it looks more like an inevitability than it ever has before.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.