(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Salvadoran Oscar Alberto Martinez and his 23-month daughter, Angie Valeria, dead on the shore of the Rio Grande in June, 2019. Three-year-old Syrian Alan Kurdi dead on Turkish sand in September, 2015. Both images are deeply disturbing. Both embody immigration crises an ocean apart; the dynamic in each is very different.

Like the European Union in 2015, the U.S. clearly faces a peak of undocumented immigrant arrivals. In October 2015, asylum seeker arrivals in the EU across the Mediterranean reached the all-time record of 222,800. In May, 2019, the U.S. reported 144,278 “apprehensions and inadmissibles” (many of whom would have claimed asylum, whether or not they fit the strict definition of those fleeing persecution) on its southwestern border, the highest for the month of May since 2000. Both numbers amount to .04% of the population of the EU and the U.S. respectively. Both appear to have overwhelmed the resources of the world’s biggest trading bloc and the world’s biggest single economy; both have resulted in the death of people who tried to bypass the overloaded official channels to escape desperate living conditions.

I would argue, however, that the differences are more significant than the similarities.

The number of Mediterranean arrivals in 2015 signifies how many people got across to Europe, forcing the authorities there to process their asylum claims to the best of their ability. The number of “apprehensions and inadmissibles” in the U.S. is how many people were caught trying to cross (they swam the river like Martinez, scaled the border fence or tried to run through a gap in it) or pushed back at legitimate border crossings after a cursory inspection. They are either prosecuted for crossing the border illegally or simply turned back. They do not get a hearing of their asylum claims.

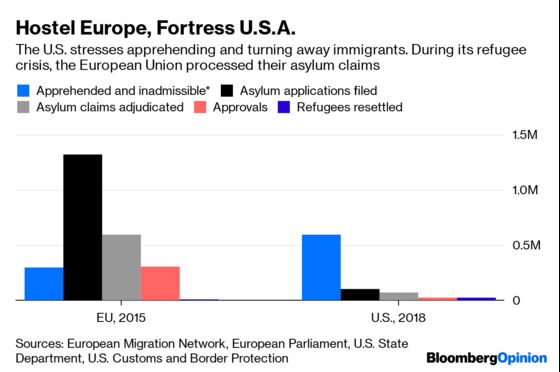

The more relevant number to consider, then, is how many asylum claims European and U.S. authorities have been trying to process and how many decisions they were making.

U.S. asylum statistics are only available for the month of January this year and a comparison between 2015 in Europe and 2018 in the U.S. is imperfect since the U.S. wasn’t at peak arrivals last year. It’s also the case that some asylum applications remain in the U.S. court system for a very long time, while decisions at the border are made by asylum officers, not judges. It is, however, still instructive.

Under the Trump administration, the U.S. has tried to accept as few asylum applications (filed on U.S. land) as possible. It has also drastically cut refugee admissions from third countries. The U.S. strives to prosecute everyone who enters the country illegally.

During its refugee crisis, the EU, by contrast, decided to process lots of asylum claims, in part because it couldn’t send most of the new arrivals back across the Mediterranean and in part because of genuine humanitarian concerns. European countries worked feverishly to streamline their processing systems, used school buildings, tent cities and defunct airplane hangars to house the asylum seekers.

As a result of these different approaches, the ratio of people receiving asylum and refugee papers to those arriving in search of protection reached 19% in the EU in 2015 and 5.8% in the U.S. in 2018. Given the difference between the EU and the U.S. systems, not to mention their own respective complexities, direct statistical comparisons are difficult. But in general terms, the EU has in recent years been more hospitable.

In effect, by turning people away or apprehending them at the border, the U.S. is protecting a processing system with an extremely low capacity. Even given the small number of applications filed, the U.S. faces a backlog of “affirmative” asylum cases (those settled by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services rather than the courts) – 325,277 of them in January 2019, according to the State Department. The German processing system, which took on a much bigger caseload during the refugee crisis, initially suffered from backlogs, too, but eventually worked through them.

Where Europe, overwhelmed, tried to rise to the challenge, the U.S. has effectively operated like a besieged fortress trying to repel attacks. Both the U.S. and Europe face all but permanent immigration challenges (African migration to the EU is as unlikely to dry up as Central American migration to the U.S.). The U.S. approach creates tension and bottlenecks; the European approach allows for more flexibility during almost inevitable future crises.

In the end, it matters little to those living in war-torn Syria, suffering in oppressive Eritrea or gang-infested El Salvador that existing rules classify some people as legitimate refugees and others as economic migrants. People from any of these places will seek safety and a better life, and the difficulty of getting into a safer country will always be lower to them than that of surviving extreme hardship at home.

Both the EU and the U.S. can afford to take in more of them than they do, the political toxicity of the issue notwithstanding. But even under current rules, giving these people a chance to file their asylum claims and tell their stories is fairer, more humane and worthier of law-governed societies than pushing them away.

The European Union ran a major naval operation in the Mediterranean during the refugee crisis, trying to turn back immigrant boats when possible or rescue the asylum seekers when that couldn’t be done. There were injustices and failures. People still died, of course. Alan Kurdi's family took an inflatable boat from Bodrum, Turkey, to the Greek island of Kos – a perilous a 2.5 mile voyage in such a vessel – and it didn’t get far before the overloaded boat capsized.

Can the U.S. afford to do better? I think it can. I walked the U.S. bank of the Rio Grande in 2016 and found the wet clothes of recent illegal crossers discarded in the bushes. The Rio Grande is treacherous, but it’s not the Mediterranean – it’s basically a narrow muddy stream with lots of bridges across it. Now, however, an image as heart-wrenching as that of Alan Kurdi exists for the Rio Grande crossing.

I can’t help thinking what would have happened if the U.S. adopted the European approach, letting in the asylum seekers and working on the fly to improve reception facilities and streamline application processing. There would have been no need for Martinez to try to swim that river. He and his daughter could have crossed a bridge. They’d have filed their applications and, if the authorities rejected them, they could have fought on with pro bono legal help, as many rejected asylum seekers have dome in Europe. And if they still ended up deported, at least they’d be alive.

There’s a German ship named after Alan Kurdi now. It picks up asylum seekers in the Mediterranean and tries to get them to European ports. Perhaps a bridge across the Rio Grande will someday be named after Angie Valeria Martinez. People will walk across it and get their chance.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Therese Raphael at traphael4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.