(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Twitter Inc.’s decision to ban political ads appears to be designed to make the company look better than Facebook Inc., which has controversially lax political advertising rules. But let’s face it: Twitter benefits from political pronouncements without having to charge those who spew them.

In a Twitter thread announcing the ad ban, Twitter Chief Executive Officer Jack Dorsey wrote:

A political message earns reach when people decide to follow an account or retweet. Paying for reach removes that decision, forcing highly optimized and targeted political messages on people. We believe this decision should not be compromised by money.

This implies that it’s OK for a politician with a big organic following to spread messages, be they true or false, but not OK for that same politician to amplify these messages by paying for them. It’s the opposite of the stand Facebook has taken: It uses third-party fact-checkers to verify messages that are spread organically (and, on a paid basis, by everyone except politicians) but gives political candidates free rein to say whatever they’re legally allowed in paid advertisements.

But the reason Twitter wants to do the opposite of Facebook is that it profits in a completely different way from political speech than Facebook does.

During the 2016 U.S. presidential election, social media companies actively vied for political business, seconding employees to campaigns to help them develop the most effective ads in what Daniel Kreiss from the University of North Carolina and Shannon McGregor from the University of Utah described as “subsidies of expertise.” The idea was to build relationships with political players and increase revenues in exchange for making campaigns’ political communications more effective. Nu Wexler, Twitter’s associate communications director at the time, told the researchers that it was clear why Trump’s campaign embraced the help:

The Trump model was that they… rented some cheap office space out by the airport, a strip mall, and they said it’s going to be Trump Digital. They had the companies, the advertising companies, social media companies come down there [San Antonio] and work out of that strip mall. And we did it, Facebook did it, Google did it…. I think they did it for two reasons. One; they found that they were getting solid advice and it worked, and two; it’s cheaper. It’s free labor.

This approach appears to have worked better for Facebook than for Twitter. During the campaign for the 2018 U.S. midterm election, Facebook collected $284 million in political advertising revenue, according to the nonprofit Tech for Campaigns. Twitter, for its part, sold less than $3 million of political ads during that election cycle, according to its Chief Financial Officer Ned Segal.

Tech for Campaigns, which notes that Facebook and Instagram ads account for a lion’s share of political digital spend, followed by Alphabet Inc.’s Google search and YouTube ads, says Twitter’s relatively small reach and limited targeting opportunities make it less attractive.

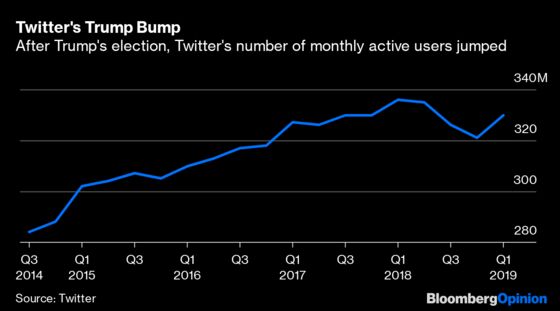

Instead of developing a political ad sales business like Facebook, Twitter developed a political dependency of a different kind. In February 2017, soon after Donald Trump’s inauguration, Richard Greenfield, then an analyst at BTIG, upgraded Twitter’s stock from “neutral” to “buy” in a note titled “The Twitter President Gives Twitter a Second Chance.” Greenfield argued that with Trump’s election, the social media company had been “thrust into the global zeitgeist.” Indeed, in the first quarter of 2017, the number of Twitter’s monthly active users jumped by 9 million, the most since early 2015.

Twitter’s status as the U.S. president’s chosen platform for interacting with voters is a matter of prestige. Besides, Twitter has a journalist-heavy user base; a quarter of the service’s verified users are journalists and media outlets. When politicians use the platform — and Trump’s example made it almost de rigeur — a journalist simply cannot stay off it. Collectively, politicians and journalists advertise the service to everyone else — free of charge.

Whether the Twitter reach of someone like Trump is really organic is questionable. Last year, the software firm SparkToro, which offers some Twitter analytics tools, concluded that 61% of Trump’s followers were fake, a lower follower base quality than average for politicians. At the same time, news outlets amplify what Trump says in his tweets — often, as a recent study showed, without debunking his false claims. It’s not clear in what way this situation is morally better than the transparent dissemination of politicians’ quibbles for money, in the form of ads.

In fact, I’d rather see a misleading statement by a politician clearly marked as an ad than endlessly replicated on my Twitter feed as organic content. It’s hard to disagree with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s contention that it makes more sense to increase political advertising transparency than to impose a complete ban on such paid content.

Unfortunately, neither Twitter nor Facebook really has a solution to the problem of lies spread by politicians as they campaign. And it’s not just because by cracking down on these lies, Facebook would lose revenue and Twitter its status as the essential political platform. To be fair to both companies, one of the only ways to place responsibility for fact-checking and filtering information squarely on them would mean a big regulatory leap: It would require recognizing them as media outlets rather than platforms for every possible kind of speech. Since that’s very unlikely to happen, the filters need to be in our heads as readers and voters.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.