Trumpism Finds a Home of Sorts in France’s Eric Zemmour

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When discussing the upcoming presidential election in France, all conversations lead to Eric Zemmour. The far-right pundit has soared in the polls after hinting at a run for the top job. His cerebral shock-jockery and populist rhetoric echo a blend of Donald Trump and Tucker Carlson, with some distinctly French characteristics.

Bring up Zemmour’s current vote share of 16% at social gatherings — which puts him in second place after president Emmanuel Macron, with around 25%, and in the final run-off between candidates — and the reactions will vary from disbelief to complacent laughter, until an inevitable admirer sheepishly pipes up. These may be early days, but there is momentum here, and Macron can’t assume it will fade.

To be clear, all polls indicate that the incumbent would handily best Zemmour in a run-off. But by splitting the field further in an already fragmented race — there are currently around 30 candidates — Macron could find himself fighting on all fronts without knowing who his real rival will be. More worrying is that Macron has trouble inspiring enthusiasm and voter turnout, while Zemmour is firing up new followers who were once apathetic.

The parallels with Trump are of style rather than substance. Zemmour doesn’t share the Donald’s obsessions with real estate or China. What he does have is a sense of declinism: “Things were better before” is a familiar refrain. Then there’s his scapegoating and simplism: If only there were no immigrants and industrial jobs back onshore, the economy would prosper. His choice of language — “rapists, assassins” — to describe immigrants evokes Trump, too. As does the difficulty of the media to hold him to account — a paparazzi photo showing 63-year-old Zemmour in the arms of his 28-year-old adviser only served to humanize him.

And although Zemmour isn’t a promoter of QAnon or anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, he walks a similarly paranoid path. He is a fan of the racist “Great Replacement” theory, made notorious by white supremacists in Charlottesville in 2017. The fact that he is of Algerian-Jewish origin makes his open courting of anti-Semites all the more cold and calculating. He’s gone to great lengths to whitewash the Vichy regime and cast doubt on the Dreyfus Affair.

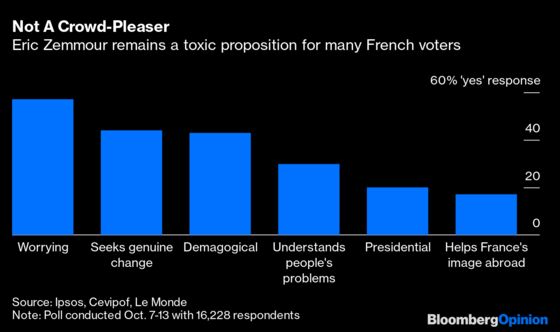

All of this makes Zemmour a toxic figure to many people — 70% of voters don’t see him as presidential material, and more than half are worried by him. But his rise highlights a broader rightward shift in post-pandemic politics. Covid-19 has strengthened the conservative urges of the French, with a majority supporting the idea of closing the country further to immigrants — that’s more so than in Italy, Germany or the U.K. This is dragging the presidential debate further to the right, where Macron is not in his element.

What’s more, it’s not clear who the president is really up against. What if Zemmour fails to displace the National Rally’s Marine Le Pen, who has been trying to make her party more palatable to the center-right and no longer wants to quit the euro? What if the European Union’s top Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier makes it through to the final rounds of voting, by playing on divisions within his center-right party and promoting his long political experience in Europe? These rivals would require different strategies.

Hence why Macron is focusing on his ability to offer stability to an electorate that, polls suggest, is worried about purchasing power above all else. The president is doling out huge subsidies to get the French through a hard winter. He has pledged 3.8 billion euros ($4.4 billion) for heating bills and a freeze on gas tariffs. The result is a 5% projected budget deficit next year. “Whatever it takes” is a potent tool.

Focusing on the economy also tempts Zemmour into territory where he is weakest — his recent pledges to cut taxes on gasoline and remove new speed limits for cars don’t chime with a net-zero world. He occasionally flatters the center-right with talk of trimming the generous welfare state and cutting business taxes, and makes clear he wouldn’t pull France out of the euro. But he always brings it back to his focus on “identity inequality” over “social inequality.”

There are two main unknowns with Zemmour’s candidacy. The first is whether he will even be a candidate. The second is whether he can expand his support beyond the far right. His dream is to cobble together a following made of chunks of Le Pen’s National Rally, the conservative wing of the center-right Républicains and disillusioned voters from other walks of political life. But so far he’s only really siphoned votes from Le Pen.

It is too early to say what will happen next. French presidential elections always take unexpected turns: Scandals or surprises can kill off aspirants. Le Pen still has her admirers. The center-right may choose a strong candidate in the end.

But Macron will need to take the threat of Zemmour seriously, whatever the polls say. The president knows that to get turnout on election day in April, he will need to stoke the one thing he doesn’t inspire: excitement. And if Zemmour really does get to the second round, that will pit Macron’s loyal following of urban, white-collar pro-Europeans against an anti-Republican front. That’d be no laughing matter.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the European Union and France. He worked previously at Reuters and Forbes.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.