(Bloomberg Opinion) -- U.S. President Donald Trump is known to admire his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin. That doesn’t mean, however, that he should imitate some of Putin’s least effective policies – such as declaring war on European cheese.

In the U.S., a 25% tariff on cheese imported from the European Union kicks in on Oct. 18. In 2014, Russia banned EU cheese, and a long list of other products, in retaliation for European sanctions imposed on Russia for its aggression against Ukraine.

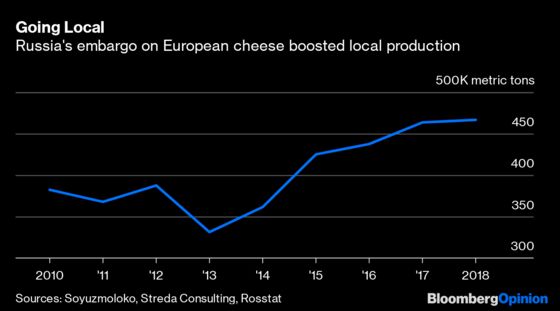

For Putin, the embargo’s goal was twofold: To hit Europeans where it hurt and to give domestic producers a chance to develop in areas where they were stunted by competition from imports. Cheese manufacturing was one such area. In 2013, Russia produced 330,000 metric tons (727 million pounds) of cheese and imported 356,000 metric tons from the EU. Trump’s goals in his trade war are similar: He’s punishing the EU for “treating the U.S.A. very badly” on trade and trying to boost domestic production and jobs.

It’s hard to see how he’ll achieve either of those goals with cheese, especially if the Russian experience is any guide. It’s consumers who ended up punished.

The embargo did boost domestic cheese production by eliminating competition. But local producers never made up for the drop in EU imports.

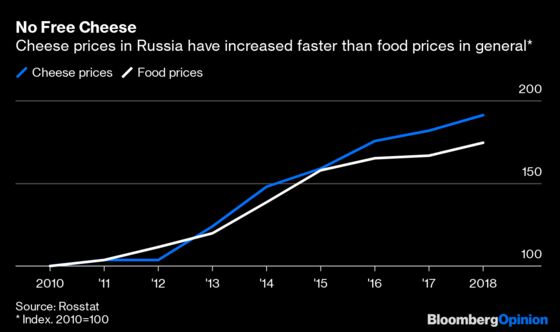

They didn’t have to. Suddenly, they could charge much more for their often inferior products. They had no idea how to replicate Roquefort; matching its price turned out to be easier.

Russians responded by switching to what are kindly called “cheese products” made with vegetable fats like palm oil. In 2013, only 87,000 metric tons of such cheese-like foods were produced. By 2016, their output jumped to 136,000 tons, increasing at a faster rate than the output of actual cheese.

In recent months, the trend has reversed – cheese consumption is on the rise and substitutes are down. But that change is driven by increasing imports rather than by domestic production, which has largely flattened out. Importers have found new suppliers that aren’t affected by the embargo, many of them in neighboring Belarus, where European cheeses are often repackaged as local for sale to Russia. Some people have even taken the matter into their own hands, buying cheese on trips to Europe. The pungent smell of ripe cheese sometimes wafts through return flights to Moscow.

The effects of Trump’s new tariffs in the U.S. will be milder. For one thing, the U.S. imported just 134,000 metric tons of cheese from the EU last year, only about 2% of total consumption; for another, the potential for local producers’ price increases is limited to 25%, a price jump true cheese lovers will probably grudgingly accept in order to keep eating real Gouda, Pecorino or any number of blue-veined cheeses. But some change inevitably will occur: U.S. producers of specialty cheeses will happily raise their prices, and as a result, some consumers will switch to cheaper, mass-produced, processed cheese.

U.S. cheese artisans have made much progress in recent years when it comes to quality. With Trump’s tariffs shielding them from the European competition, there won’t be much need for them to keep improving, but they’ll be able to charge more. Meanwhile, the mostly small companies that import European cheeses – about $1 billion worth of them last year – may be threatened because switching to local products is unlikely to set off the potential drop in imports. In Russia, “import substitution” failed to do that.

As for the EU, it’ll probably survive the U.S. tariffs with minimal losses. It reacted to the Russian embargo with some emergency aid to food producers, with the dairy sector receiving 770 million euros ($846 million). Cheese exports dropped slightly, but then quickly recovered and continued growing.

By following in Putin’s footsteps, Trump won’t punish the EU as much as U.S. consumers and small businesses. The domestic industry will get something of a windfall, but, if the Russian example is any indication, it won’t use it effectively.

The best way to fight unfair trade practices – for the EU sets prohibitive tariffs that can exceed 60% on some kinds of cheese – isn’t to retaliate. It’s to drive down prices and keep working on quality and the international reputation of U.S. products. U.S. cheesemakers still have a lot of work to do on those fronts. It’s counterproductive to protect them from higher-quality competition.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.