(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President Donald Trump was elected on a promise to reduce or eliminate the U.S. trade deficit. Instead, that deficit has risen to heights not seen since before the Great Recession. Reducing it will require a smarter approach than Trump’s failed tariff policies.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic struck, the U.S. trade deficit had increased under Trump from about $500 billion a year to about $575 billion. The deep recession caused by the pandemic should have reduced that imbalance. But the deficit hasn’t followed the normal pattern this time:

That’s especially odd considering the pandemic has led to a massive contraction in global trade. That tends to shrink global imbalances; and indeed, trade surpluses and deficits are shrinking almost everywhere. But the U.S. is bucking that trend, running an ever-larger deficit. And on the other side of the ledger, China’s surplus is expanding. It seems nothing can stop Americans’ desire to buy Chinese-made goods or China’s willingness to sell them to the U.S. on credit.

Some might argue this is a good thing. After all, a trade deficit means China is giving the U.S. valuable physical stuff, while getting nothing but IOUs in return. Doesn’t the U.S. come out ahead in that deal?

Unfortunately, probably not. The U.S. will someday have to either repay those IOUs, inflate away the debt or default. None of those are particularly appetizing options. Consuming today and promising to pay for it in the future leaves a burden for the next generation of Americans.

What’s more, a trade deficit also means foreigners hold ever more U.S. debt, which probably reduces the power of monetary policy to support the economy in recessions. Some claim a big trade deficit also erodes the industrial base; if Americans get used to consuming things they don’t build, then their technical expertise and supply networks could dwindle, making it an uphill struggle to rebuild industry in the future.

But even if trade deficits are bad, getting rid of them isn’t so simple. Trump bragged it would simply take an aggressive commitment to tariffs, but that approach backfired. It’s not hard to see why; the tariffs raised the cost of imported goods, making life harder for U.S. producers.

One alternative is export subsidies. Though World Trade Organization rules officially forbid monetary subsidies to exporters, there are plenty of ways to get around the ban (as China has shown). Not only would export subsidies potentially reduce the trade deficit, they might also raise productivity by pushing U.S. companies out of the small, comfortable domestic market into the big, competitive world market.

But when it comes to U.S.-China imbalances specifically, export subsidies probably wouldn’t do the trick. Unlike, many countries, China’s government wouldn’t simply accept a rebalancing. It would likely just use its own subsidies, along with non-tariff barriers, to counter any U.S. effort. And as those policies are semi-hidden — carried out via the dense network of connections between Chinese companies and the government — trying to force China to stop would be like playing whack-a-mole.

A simpler approach would be to push China to revalue its currency. This would be like the Plaza Accord of 1985, in which the U.S. pressured Japan, Germany, and France to appreciate their currencies against the dollar. That approach was a partial success: European trade surpluses shrank, but the U.S.-Japan imbalance persisted for years. Still, the Plaza Accord approach is promising.

The problem, again, is that China is unlikely to accept that outcome. China’s leaders tend to believe the 1985 agreement caused Japan’s eventual bubble and bust later in the decade. They’re probably wrong about that; Japan’s bubble and bust happened for unrelated reasons. But it means China is unlikely to accept a large appreciation of the yuan except under extreme duress. The U.S. would need to threaten Trump-style policies of tariffs and export restrictions that would end up hurting both economies.

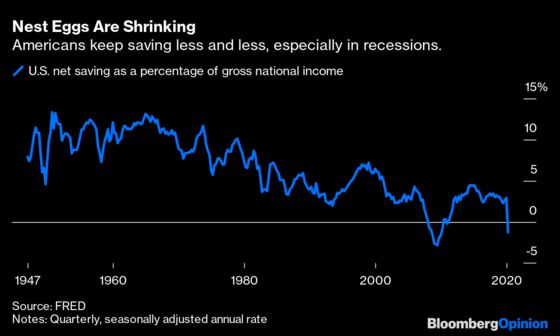

A final idea is to raise national saving. When national savings rates go up, it pushes capital to flow overseas, which tends to make the dollar cheaper and U.S. exports more competitive. The fact that U.S. net national saving has been falling in recent years might be one reason the trade deficit is so stubbornly high:

China, which has shown some signs of opening up to more foreign financial investment, might be willing to allow the capital inflows, even if it meant a more expensive yuan.

So while the overall U.S. trade deficit can be brought down, the bilateral imbalance with China will be the toughest nut to crack. Ultimately, it may simply take a sustained pressure campaign on many fronts — pushing China to appreciate the yuan, subsidizing exports, working to reshore American industry, raising national saving, etc. Ultimately China’s government will get the message that continued imbalances are not worth the trouble and allow their surplus to shrink.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.