Trump Plays the Game of Gaming the Presidential Debates

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Donald Trump is musing about snubbing next year's presidential debates, skipping the traditional verbal fencing match between the two candidates for the nation's highest elected office. In practice, despite what he's indicating, Trump almost certainly will participate. But game theory shows that it can make sense for him to suggest otherwise.

Trump isn't exactly known for his talents as a debater, and most observers of his three encounters with his 2016 opponent, Hillary Clinton, concluded that she got the better of him. Yet Trump's most ardent supporters may not care whether he participates in the debates, so Trump has little upside with them if he does agree to debate.

Even so, Trump will almost certainly show up at the end of the day -- for image reasons, if nothing else.

But that doesn't matter much for the game Trump's playing right now.

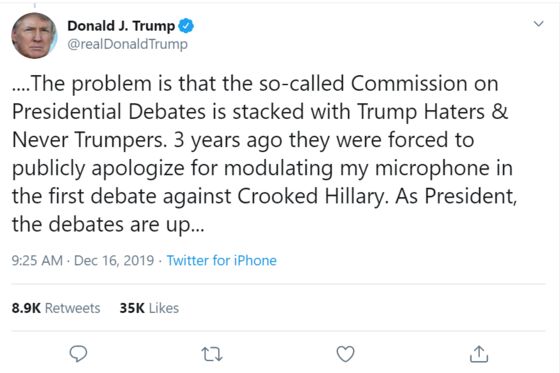

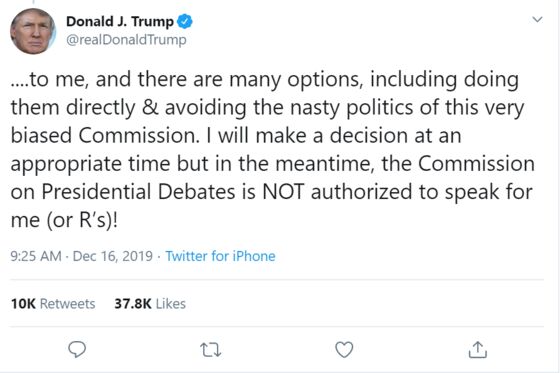

By threatening to boycott, Trump creates pressure to structure the debates in a way that's more to his liking in hopes of getting the debate's organizers to shade the terms and conditions a bit in his favor. His repeated intimation that a malfunctioning microphone in one of the 2016 debates was intentional is one card he frequently plays in this effort.

This isn’t bad use of game theory, actually: The president understands that the television networks need the debates to happen as much or more than he does. The first presidential debate in 2016 had 84 million viewers. That likely made it the most-watched debate in American history, with more viewers than the last episode of "Seinfeld," and more than 80% of the viewers of last year's Super Bowl. And the Commission on Presidential Debates, the nonpartisan nonprofit that runs the debates themselves, needs the debates to happen even more, because otherwise it doesn’t have much of a purpose.

Trump himself has given credence to this idea on Twitter:

Never one for subtlety, the deal is clear: If the debates look good for Trump, he's in. If not, then -- he says -- anything could happen.

Without Trump, there's literally no show, so the commission has a strong incentive to keep him happy, or at least mollified. Trump's known for changing his mind on short notice, so the pressure stays on until the moment he sets foot on the debate stage.

The first debate is scheduled for September 2020, leaving a lot of time for Trump and the Republican National Committee to try to extract concessions, both publicly and in private.

And it's possible the commission will cave, either on its own, or due to pressure from the networks. But it shouldn't, or at least not soon. If it gives in early, that signals weakness and opens the way for Trump to up his demands. To be sure, the commission has pushed back against Trump in the past: In one 2016 debate, when Trump wanted to seat several women who had accused Bill Clinton of sexual assault in the front row, the commission threatened to have the women removed by security if they didn’t relocate.

Paradoxically, the commission should instead signal strength and reiterate a commitment to fair and balanced debate without making any specific promises. Of course, the commission shouldn't do anything to directly antagonize Trump, since that would give him a good excuse to drop out. It should just show enough willingness to wait him out, suggesting awareness that in the end Trump’s self-regard will dictate that he show up. If the Commission manages to drive this message home, then its bargaining position strengthens, especially the closer we are to the debates themselves.

But that's a hard line to toe: Trump and the commission both need the debate to happen, but arguably the commission needs it more. So for once, those who say Trump is playing 7D-chess might have the better case to make — and if he is, he might actually win this game.

Of course, it's important to keep perspective: that's still only 12% the number of people who tuned in for the Apollo 11 moon landing.

And if the Commission holds steady long enough, it creates the impression that it isn't planning to cave in the end, since otherwise it could always have caved earlier — the same way that when an underdog makes a big investment in a new version of their product, it signals that they're planning on staying in for the long haul.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Scott Duke Kominers is the MBA Class of 1960 Associate Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, and a faculty affiliate of the Harvard Department of Economics. Previously, he was a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows and the inaugural research scholar at the Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics at the University of Chicago.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.