The Last Great Neoliberal Experiment Comes to a Neighborhood Near You

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The opportunity zones created by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 have all been set up, and the money has started to flow. When will we know if they’re working as promised to bring new growth and prosperity to distressed communities all over the U.S.? Well, maybe never — the opportunity zone is the latest refinement of a development approach previously known in the U.S. as the enterprise zone and the empowerment zone, and attempts to suss out the economic impacts of those have delivered notoriously muddled results.

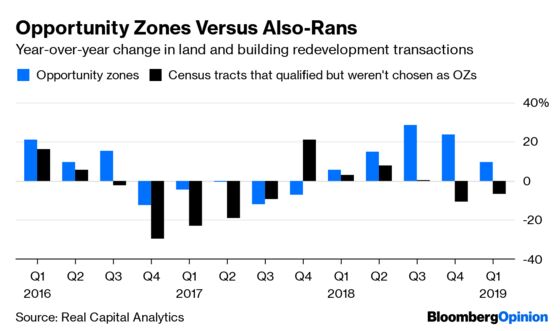

Still, we can at the very least say that the opportunity zones — 8,762 economically disadvantaged census tracts where investors receive favored capital gains tax treatment — are getting some investment. Real Capital Analytics, which tracks commercial real estate transactions, just released data comparing activity in opportunity zones and in census tracts that met the criteria for inclusion but weren’t chosen by their states’ governments:

Transaction volume hasn’t just been rising faster lately in opportunity zones than in also-ran tracts; it’s been rising faster there (at least until the first quarter of this year) than in the rest of the country, too.

Then again, as is apparent from the above charts, the opportunity zone census tracts were already outperforming everyplace else before they were designated, too. A recent report from Reonomy, another commercial real estate data provider, indicates that they were laggards for most of the past two decades, which is perhaps a sign that the states have mostly picked places that were just starting to rebound. Disentangling cause and effect here is hard, as it has been throughout the history of enterprise/empowerment/opportunity zones, although the design of the opportunity zone program may lend itself better to measurement than some of its predecessors.

The concept is usually credited to Peter Hall, a British geography professor who after a visit to East Asia in 1977 proposed in a speech that the U.K. establish, as he paraphrased it a few years later, “a genuine mini Hong Kong in some derelict corner of the London or Liverpool docklands, representing an experimental alternative to the mainstream British economy.” Hall, who died in 2014, was a Labour Party-supporting expert on urban planning, but his idea quickly caught on with planning-averse conservative/libertarian politicians in the U.K. and U.S. “Enterprise zones, it seems,” Hall noted with bemusement in 1982, “have become the standard urban policy package of radical right wing administrations in English-speaking countries.” In the U.K., the newly elected government of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher put in place a program of urban enterprise zones featuring reduced regulation and taxes in 1980. In the U.S., President Ronald Reagan tried but never succeeded in creating an enterprise zone program on the national level, but 40 states started their own and, in 1993, President Bill Clinton succeeded in getting Congress to approve the Empowerment Zones and Enterprise Communities Act.

This bipartisan appeal was a trademark of enterprise zones and their ilk. They united concern for the poor with a belief in free enterprise in a package that pretty much summed up the era of neoliberalism, which saw markets as the best tools for attacking social problems. The zones also, it must be said, had little demonstrable positive economic effect:

Unfortunately, research into the effects of these enterprise zone programs in the U.S. has found at best mixed results, with little consensus in the literature as to whether they are beneficial.

That verdict comes, interestingly enough, from the document that helped launch the opportunity zone movement: a 2015 paper, “Unlocking Private Capital to Facilitate Economic Growth in Distressed Areas,” by Jared Bernstein, former chief economic adviser to Vice President Joe Biden, and Kevin Hassett, the current chairman of President Donald Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers. The paper was commissioned by the Economic Innovation Group, a Washington think tank that had just been launched by Sean Parker, the billionaire co-founder of Napster and early backer and then-president of Facebook Inc.

Parker is perhaps most identified with the words uttered not by him but by the actor who portrayed him in the movie “The Social Network,” Justin Timberlake: “A million dollars isn’t cool. You know what’s cool? A billion dollars.” That, to some extent, was Bernstein and Hassett’s reasoning in their paper. Previous enterprise zone efforts in the U.S. had been too limited, scattershot and complicated to attract large-scale investment:

Previous programs left many potential sources of investment untapped. There was no structure in place to encourage investors to exit existing investments, for example, and bring their realized gains into enterprise zones. There also was not a structured way to involve intermediary groups, such as banks, private equity, and venture funds, in investing in enterprise zones, although these groups generally can bring large resources to projects and have the potential to invest in companies that may thrive within an area. The emphasis on individual businesses instead of larger structures and institutions may indeed be part of the reason for the tepid results of enterprise zone programs.

What was needed, they concluded, was “a simpler, targeted approach” to lure institutional investment into economically depressed communities. A little more than two years later, that approach was law. Steve Bertoni described how it happened in an entertaining Forbes cover story a year ago: Parker enlisted Republican U.S. Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina and Democrat Cory Booker of New Jersey as leaders of the effort on Capitol Hill, and he stalked the halls of Congress to buttonhole lawmakers himself. Scott and Booker introduced the plan as a stand-alone bill in 2016, with another bipartisan pair doing the same in the House. Then they, as Bertoni put it, “decided it was best to wait for some fast-moving legislation to hitch it to.”

That legislation turned out to be the 2017 tax bill. The House version didn’t include opportunity zones but the Senate one did, thanks in large part to Scott’s presence on the Finance Committee, and it survived in conference committee, too. One big mark in its favor was that, in a bill that the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated would reduce tax revenue by $1.4 trillion over the next 10 years, its projected cost was a mere $1.6 billion.

To qualify for opportunity zone status, a census tract generally (there are a couple of other ways for some tracts that don’t quite meet these criteria to qualify) has to have a poverty rate of 20% or more, or a median family income that’s 80% or less of the state or metropolitan-area median. Investors can defer capital gains from past investments and be exempted from some or all taxes on new capital gains by putting the money into “qualified opportunity funds” that invest in commercial and industrial real estate, housing, infrastructure or businesses in the zones.

More than half of all U.S. census tracts qualified for inclusion, but governors of states and territories, and the mayor of Washington, were charged with winnowing that list down. That task was completed by the middle of last year, and the chosen zones — which constitute 12% of the nation’s census tracts and can be perused most easily via the Economic Innovation Group website — are a mix of areas that I think everyone can agree are quite disadvantaged and others that happen to have met the criteria but are right next to prosperous areas and might have attracted investment in any case.

Overall the selections tilt in the former direction: According to an Urban Institute analysis, the median 2012-2016 household income in the opportunity zones was $33,345, compared with $44,446 in the eligible-but-not-chosen tracts and $58,810 in the country as a whole. Mayors and other local officials have been deeply involved in picking opportunity zones in some states, following a template for investment devised in part by urban thinker and former Barack Obama administration policy maker Bruce Katz that aims to “spur growth that is inclusive, sustainable and truly transformative for each city’s economy.”

Still, as Noah Buhayar, Caleb Melby and Lauren Leatherby of Bloomberg News have been reporting, some of the opportunity zones that have investors and developers most excited are in places like far-from-struggling downtown Portland, Oregon; an already-under-development “live, work, play paradise” just north of Miami; and the booming neighborhood in the New York City borough of Queens where Amazon.com Inc. was going to locate a new headquarters before backing out in the face of local opposition. Real Capital Analytics predicted late last year that “the NYC Boroughs, Los Angeles and Phoenix may prove to be the most active markets for opportunity zone funds given their larger market size and their relatively high proportion of opportunity zones.”

There is of course a balance that must be struck between investment viability and giving help to areas that truly need it. There’s also a risk that investments in poor neighborhoods will drive current residents out rather than enriching them, not to mention the risk that opportunity zones will turn out to be more successful in reducing the taxes of real estate investors — who already got big breaks from other provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act — than in stimulating productive investment. With Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, a former hedge fund manager and Goldman Sachs partner, in charge of setting the rules for opportunity zone investment, critics such as Samantha Jacoby of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities have charged that they’ve tilted way too far in the direction of making life easy for investors rather than ensuring that investments improve the lives of zone residents. Even the Economic Innovation Group is now pushing for stronger data collection rules so that “the success of the Opportunity Zones policy can be properly evaluated.”

Opportunity-zone idea man Bernstein, a senior fellow at that very same Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, told me this week that, while he too has mixed feelings about the effort, “I think I'm less ambivalent than a lot of my fellow progressives.” He said he’s been mostly encouraged by the states’ opportunity zone choices, and by the level of investor interest so far. Still, as he put it in a Washington Post op-ed early this year:

If OZs turn out to largely subsidize gentrification, if their funds just go to places where investments would have flowed even without the tax break, or if their benefits fail to reach struggling families and workers in the zones, they will be a failure.

Bernstein also wrote that, in fighting poverty, he preferred “direct hits” such as government-financed infrastructure investment and guaranteed health care and housing to market-dependent “bank shots” such as opportunity zones. This is true of left-leaning thinkers in Washington more generally these days — the summer issue of Democracy Journal, a past source of such Democratic Party policy ideas as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, features a multi-author symposium titled “Beyond Neoliberalism.” Voices within the Republican Party, including President Trump on trade matters in particular, have been departing from the markets-know-best policy as well. We may not see anything else like opportunity zones come along for quite a while. Unless, that is, they turn out to be so successful that the evidence isn’t inconclusive this time around.

Highly recommended: his book "Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880."

These are the static revenue estimates. The JCT's macroeconomic analysis of the bill's effects cut the overall 10-year cost to about $1.1 trillion but did not break things down to the level of including a revised estimate of the cost of opportunity zones.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.