(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President Donald Trump’s administration is reportedly considering an executive order that would require all academic research financed by the U.S. government to be published without paywalls. This follows on legislation passed by Congress during previous presidencies that in 2008 required research papers funded by the National Institutes of Health to be made available to all no later than 12 months after publication and that in 2014 extended the policy to all federally funded research. It would also resemble the European Union’s Plan S, which is set to require all research funded by 19 European agencies to be published open access starting in 2021.

Open access to scientific research hasn’t exactly been a big theme at the president’s rallies, and it’s a bit of a surprise to see such a proposal coming from his less-than-science-friendly administration. When Robert Harington, associate executive director for publishing at the American Mathematical Society, broke the story last month in the Society for Scholarly Publishing’s group blog, the Scholarly Kitchen, he said it appeared to be an initiative of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, headed for the past year by research meteorologist Kelvin Droegemeier. A few days later, David Kramer of Physics Today confirmed with “an administration source” that something was in the works, but said it emanated from elsewhere in the White House.

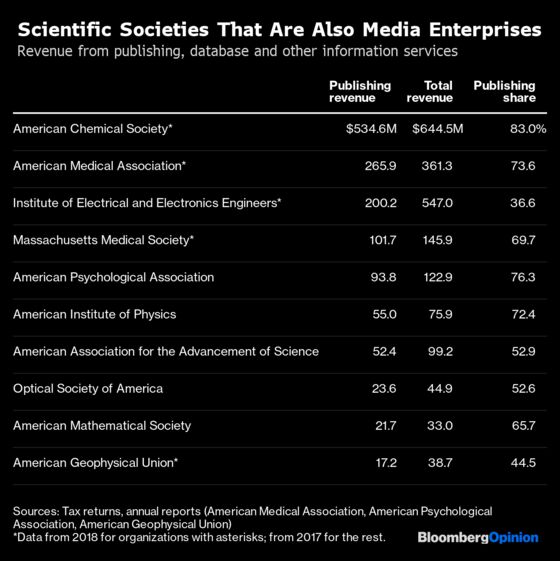

So that’s all very mysterious, and I really can’t tell you how likely such an executive order is, or whether it would hold up in court. But I do have something to say about the reaction. A long list of organizations signed a letter just before the holidays arguing that such a policy “would jeopardize the intellectual property of American organizations engaged in the creation of high-quality peer-reviewed journals and research articles.” For-profit journal publishers Elsevier and Wiley were on the list, as one might expect, but most of the 137 signees were nonprofit groups such as the American Chemical Society, American Medical Association and American Geophysical Union. A separate letter protesting the plan netted the support of 60 nonprofit scientific societies.

Some of these organizations have large memberships outside of academia, and get most of their publishing revenue from endeavors other than scientific journals. At the American Chemical Society, for example, the majority of that $534.6 million in “information services” revenue comes from its Chemical Abstracts Service, which maintains “the world's largest collection of chemistry insights,” including “158 million organic and inorganic substances” and “68 million protein and nucleic acid sequences.”

But at others — such as the Massachusetts Medical Society, publisher of the New England Journal of Medicine, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, publisher of Science — it really is chiefly about the journals. The AAAS breaks things down more granularly than most in its tax returns, which reveal that in 2017 subscriptions to Science brought in $37.7 million, advertising $12.9 million and other “Science products” $5.9 million. AAAS annual reports, meanwhile, indicate that its publishing operations generated about $12 million more a year than they cost in both 2017 and 2018, for an operating margin of a little more than 20%.

That’s a nice little business, the profits from which help pay for the organization’s overhead and its policy and educational programs. Washington-based Science, in existence since 1880, is generally seen as one of the world’s top two multidisciplinary research journals, the other being London-based Nature, which was founded in 1869 and is published by the for-profit Springer Nature Group. Both feature reported pieces and reviews that wouldn’t be subject to the open-access requirements of Plan S or the rumored U.S. executive order alongside peer-reviewed research articles that would. Interestingly, neither the AAAS nor Springer Nature were among the signatories to the anti-executive-order letters discussed above — although an AAAS representative hinted that this was mainly because there was no actual executive order to object to yet.

Still, it seems clear that if all government-funded research had to be published immediately without paywalls, the business models of Science, Nature and a lot of other scientific journals would have to change. Even though the authors of research articles and the peer-reviewers who vet them generally aren’t directly compensated for their efforts, publishing the articles does cost money — for copy-editing, herding peer reviewers and a long list of other tasks that can seem awfully minor and arcane but do add up.

The main alternative that has emerged for funding all this is for authors (or their employers or funders) to pay to have articles published. There are signs that this may be a less sustainable model than subscriptions. At the Public Library of Science, a pioneering open access publisher founded in 2001, publication fees brought in $31.7 million in 2018, but expenses added up to $38 million. Universities have begun to negotiate deals with big publishers that allow their faculty’s research to be published without paywalls while giving faculty and students access to paywalled articles. Although the giant American Chemical Society has embarked on such a “transformative” deal with Germany’s research-focused Max Planck Institutes, smaller scientific societies are likely to find it harder to make the economics work.

The reactions I’ve seen on Twitter to the possible executive order and the scientific societies’ letters in opposition to it do not indicate a lot of sympathy for their plight. University of California at Berkeley biologist Michael Eisen, one of the founders of PLoS, declared that he was renouncing his membership in the Genetics Society of America because it supported “this despicable letter.” Elaine Westbrooks, university librarian at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, questioned, among other things, why libraries should continue to “shell out big money to these scholarly publishers and so called learned/scholarly societies if they are not even trying to rethink this racket?” Summed up Jack Clark, policy director at artificial-intelligence laboratory OpenAI (and a former Bloomberg News journalist):

Are these reactions representative of the sentiments of most researchers? Well … maybe. A 2018 survey of U.S. college and university faculty members by academic research and consulting service Ithaka S+R did find that 64% “would be happy to see the traditional subscription-based publication model replaced entirely by an open access system,” up from 57% in 2015. But the survey results also indicated that most faculty members still think it’s important to publish in the most prestigious journals (which the scientific-society journals often are for their disciplines) and prefer journals that don’t charge publication fees. Something has to give. Over the next year or two we may begin to find out what.

The numbers in the table were culled mostly from tax returns in ProPublica's Nonprofit Explorer database. The American Medical Association and American Psychological Association don't clearly break out publishing revenue in their tax returns but do in their annual reports, so I used the latter for them. Also, the American Geophysical Union had an anomalous 2017, the year for which its most recent tax return was available, so I used numbers from its 2018 annual report instead.

The ACS doesn't break down the CAS share in its financial statements or tax returns, but during a court case in the 2000s disclosed that it accounted for about 60% of its revenue.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at sshick@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.