Trump’s Economy Isn’t as Strong as the Jobs Numbers Suggest

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For much of Donald Trump’s presidency, the economy’s historically low unemployment rate has coexisted with the president’s historically low approval rating. “The fact that we have the strongest economy in 50 years and he’s stuck at 43% approval ought to scream volumes for his language and his overreach,” one Republican pollster said recently.

That’s one explanation. There is another: The U.S. economy, far from being the strongest in 50 years, is not nearly as strong as the numbers would suggest.

Unemployment may be low, but broader measures of the labor market are still well below their peaks of the late 1990s. Workers are only considered unemployed if they are actively looking for a job, and in the wake of the Great Recession, millions of Americans gave up. That situation is changing, but slowly.

In particular, the prime-age employment to population ratio, which measures how many working-age adults have a job, stands at 80.4%. That’s only a slightly above its reading of 80.3% in January 2007, just before the financial crisis began. In April 2000, it was 81.9%.

And the current number is helped by the increasing participation of women in the labor market. For men, the prime-age employment ratio is 86.8%, 4.6 percentage points lower than its all-time high of 91.4%.

Many economists say that this difference represents long-term secular changes in the workforce. In particular, they say, far more prime-age men are disabled today than in the past. The logic, however, is a bit circular. Prime-age male employment has risen steadily during all economic expansions since the mid-1980s, falling only during a recession.

During the current expansion, the percentage of prime-age men on disability has fallen dramatically. That’s part of how job growth has continued even with unemployment near historic lows. If the expansion were more robust, then more men would be drawn into the labor force.

Indeed, that is precisely the pattern in other nations. In Germany, the prime-age employment ratio for men has grown to a record 89.6%, and in Japan it is stands at 93%.

Stalled wage growth is another sign that the labor market isn’t as tight as the low unemployment numbers suggest. According to the Atlanta Federal Reserve, wages are growing at roughly 3.7%, just above the rate in the summer of 2016 — and well below the rate of 5.4% reached in January 2001.

This is further indication that employers are responding to low unemployment by recruiting workers from the sidelines rather than giving larger pay raises to existing workers. That helps the labor market continue to heal, but it doesn’t produce the type of blockbuster economy that America saw in the late 1990s.

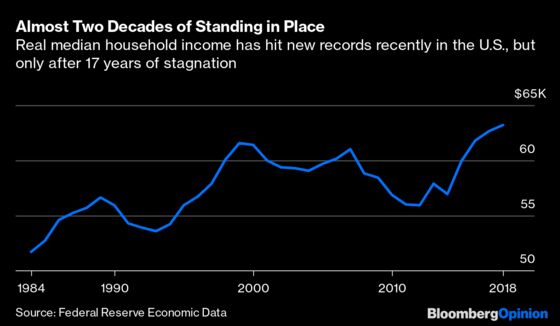

That’s reflected in household income — which has hit all-time highs in the last three years, but only after a decade and a half of stagnation. Real median annual household income in 2018 was $63,179, compared to $61,526 in 1999.

The bottom line this: In relative terms, the U.S. economy is in a better place than it has been at any time since early 2001. But that relative comparison masks the overall stagnation of the last 20 years. Trump’s “language and his overreach” may well be hurting him among many voters. But the economy is not helping him as much as it might have in the past.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Michael Newman at mnewman43@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Karl W. Smith, a former assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina and founder of the blog Modeled Behavior, is vice president for federal policy at the Tax Foundation.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.