(Bloomberg Opinion) -- On Tuesday, I published a column with the headline “U.S. Treasuries Are Not Supposed to Trade Like This.” It showed that since the federal government began issuing 30-year bonds in the 1970s, yields had never whipsawed as much as they did in the previous three trading sessions.

I thought I had the reasons figured out. The Federal Reserve would cut its key lending rate to zero in short order? That’s still the base case. Foreign bond buyers are panic buying? Indeed, Japanese investors just bought a record amount of overseas bonds. A recession seems likely? It sure does.

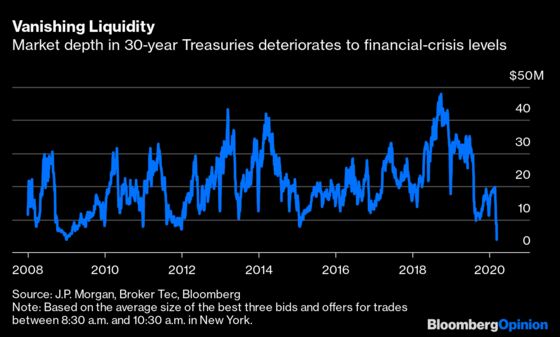

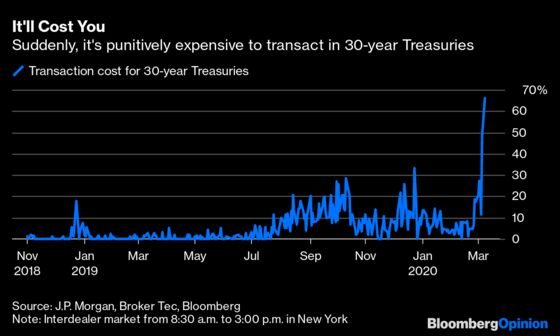

But behind the scenes, there was an even more sinister cause for alarm: A stunning lack of liquidity in what’s often billed as the world’s deepest and most liquid bond market.

The magnitude of this issue is just now coming to light thanks to analysis from some of the biggest U.S. banks, which serve as primary dealers to the Fed. Investors were wondering aloud what was happening in Wednesday’s trading session, when stocks plummeted but Treasury yields climbed, creating the worst day for the combination since 2008.

Bank of America Corp. strategists have some answers. It comes down to leveraged investors, who buy cash Treasury securities and hedge the interest-rate risk with futures contracts. Because the bonds themselves are less liquid and more costly to hold on balance sheets, they’re cheaper than futures. In other words, it’s a strategy that brings in easy profits — provided, of course, that those investors don’t need to suddenly offload debt into a volatile market.

“Yields appear to have been overwhelmed by liquidity concerns,” the strategists wrote. To be specific, this is the vicious cycle they see potentially emerging without some sort of Fed or Treasury intervention:

“The risk in the current environment is that sustained illiquidity of the UST market … could cause leveraged UST investors to reduce their Treasury positions on a large scale. This would essentially result in a Treasury ‘supply shock’ as these funds reduce their positions & force dealers to sell those positions in a very illiquid market. Significant position reduction from one large leveraged UST investor would likely lead to a cascading effect whereby U.S. Treasury yields rise sharply and force liquidations from other similar investors. This would worsen conditions for dealers to intermediate risk in the U.S. Treasury market, exacerbate the rise in U.S. Treasury yields, and further cheapen Treasuries.”

It didn’t take long for word of the liquidity crunch to reach the Fed’s ears. On Thursday, it unveiled a series of actions “to address temporary disruptions in Treasury financing markets” that are tantamount to a return to full-blown quantitative easing.

In a statement, the New York Fed said it would offer $500 billion in a three-month repo operation on Thursday. It will do the same on Friday, in addition to another $500 billion in a one-month operation. It also said that rather than buy $60 billion of Treasury bills a month as planned, starting Friday, it would conduct purchases “across a range of maturities.”

“These changes are being made to address highly unusual disruptions in Treasury financing markets associated with the coronavirus outbreak,” the New York Fed said in its statement. “The terms of operations will be adjusted as needed to foster smooth Treasury market functioning.”

To see just how out of whack the $16.9 trillion Treasury market has become, particularly the long bond, check out the following two charts that Bloomberg News’s Liz Capo McCormick and Alyce Andres published in an article (which you should read in full):

Trading conditions have become so bad, in fact, that investors are being warned not to trust certain yield levels on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note. “Until retail sales next Tuesday, managers should view the range from .73% to .89% as a signal of general trading distress rather than economic or Fed fundamentals,” Jim Vogel at FHN Financial wrote. The yield reached that upper bound in late trading Wednesday. “Even a clear announcement from Washington shouldn’t send rates quickly into that zone for the next two weeks.”

As McCormick and Andres noted, that lack of clarity in the world’s borrowing benchmark creates strains in other asset classes. Notably, 10-year triple-A municipal bond yields increased by a stunning 28 basis points on Wednesday. That turned out to just be the beginning: They surged an additional 42 basis points on Thursday in what would be the largest single-day move since at least 2009. At the risk of repeating myself: Munis aren’t supposed to trade like this.

So, how to resolve this liquidity squeeze? The chatter among Wall Street banks revolves around a “buyback” program from the U.S. Treasury.

This solution centers on the dealers’ ability to make markets in “on-the-run” and “off-the-run” securities. The former are the most recently issued notes and bonds, which generally have interest rates close to the prevailing market yield. The latter can be wildly divergent — for example, a 30-year bond issued in August 1999, with a 6.125% coupon, is roughly a 10-year Treasury. But the on-the-run benchmark has a 1.5% coupon, creating a massive gap in their respective prices. By JPMorgan’s calculations, the chasm is the widest since the 2013 taper tantrum and the 2008 crisis.

A buyback from the Treasury would work similarly to any other borrower. The New York Fed would buy older, higher-coupon securities from dealers, and then presumably the Treasury would offset those purchases with bigger debt sales in the future. As Jefferies LLC economists noted, there is precedent: In 2000, when the U.S. had a budget surplus, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers initiated such a buyback program, stating that “buying back old, higher-interest debt allows us to manage the federal debt in a way that saves the American taxpayer money.”

There’d be no pretense of benefiting the taxpayer here. Rather, it would serve as a way to ease some of the trading difficulties of the past week. Bank of America envisions the Treasury buying across the curve but increasing issuance of short-term bills to finance it. The idea is that the Fed is already heavy-handed in that part of the market, with its large-scale repo operations, creating a scarcity of short-dated debt. But in theory the Treasury could also finance the buybacks with larger auctions across the maturity spectrum, which would get a larger share of the market on the run at once.

Of course, there are also structural changes to the Treasury market that can’t be papered over with buybacks. It’s no secret that high-frequency trading firms, which already dominate equities, are also taking on an increasing role in the Treasury market’s interdealer business. It’s still too soon to draw sweeping conclusions about all the causes of the past week’s trading conditions, but if they persist, it seems likely that banks and broker-dealers will point fingers at the high-frequency traders. The fact that the coronavirus outbreak might be disrupting the offices of the high-frequency traders only adds to the headaches.

Nothing feels good right now in financial markets. Investors at least thought they could count on the world’s No. 1 safe haven asset as a shelter in the storm. That notion is now in doubt. Even with the Fed’s latest bazooka, it’s an open question whether the turbulence will ease anytime soon.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.