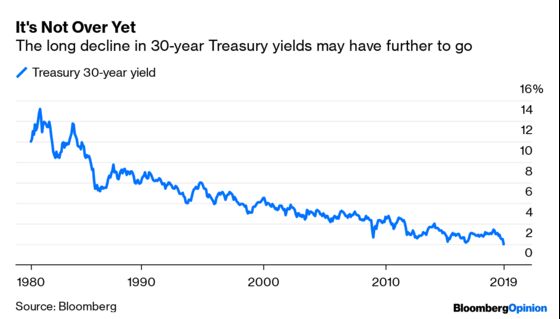

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As the 1970s came to a close, I sensed that double-digit rates of inflation were about to turn to disinflation, or smaller and smaller overall price increases. Given the close correlation between inflation and yields on U.S. Treasury securities, I forecast in 1981 a dramatic decline in the 30-year yield from what was then 14.7% to 3% and stated, “We’re entering the bond rally of a lifetime.”

After the 2007-2009 Great Recession, inflation rates continued to fall and the economic recovery was the slowest of any in the post-World War II era. So I lowered my yield target for the long bond to 2%. In recent weeks, the yield fell as low as 1.90%. Now, many are wondering whether the U.S. government debt market could join the $15 trillion of sovereign bonds globally that carry negative yields.

I’m reluctant to push my luck and make that call. Still, if the recession I believe the economy is already in deepens and is widely recognized, Treasury yields could fall further. And don’t worry about the paltry yields. I’ve never bought bonds for yield and couldn’t care less what it is, as long as it’s going down and, as a result, Treasury prices are rising. A decline in the yield over the next year from 2% to 1% would provide a 27% total return on a 30-year Treasury bond and 35% on a 30-year zero coupon bond. Those are attractive potential returns given the likely drop in stock prices.

So while a recession-related yield decline could continue the bond rally, the lure of Treasuries will depend predominantly on inflation/deflation. Over the post-World War II era, the correlation between CPI inflation and Treasuries is 60%, which is high considering all the political, military and other forces that influence yields.

I continue to believe that global deflationary forces are robust and growing despite the determined efforts of major central banks to push inflation to their universal 2% targets. Globalization, which has shifted manufacturing from Europe and North America to China and other low-cost Asian economies, is first and foremost among the deflationary forces. Others include the on-demand economy—think Uber—and the Amazon.com effect that, via smart phone apps, reduces the price of any item to that of the lowest seller.

Chronic deflation of 1% per year is quite possible, and implies a real Treasury bond yield of 3% if the nominal yield is 2%. That’s actually higher than the 2.5% average real yield of earlier post-World War II years. Treasuries would also continue to be attractive relative to negative bond yields in Europe and Japan, and also could compare favorably with stocks.

Even with 2.5% to 3% real economic growth, overall stock prices might rise just 1% per year, taking a 40% decline in their cyclically-adjusted price-earnings ratio into account. With a 2% dividend yield, total returns would average 3%, with only one percentage point over Treasury yields to account for the greater risk in equities.

“The bond rally of a lifetime” may draw to a close before long, but Treasuries might still be attractive on a yield basis.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

A. Gary Shilling is president of A. Gary Shilling & Co., a New Jersey consultancy, a Registered Investment Advisor and author of “The Age of Deleveraging: Investment Strategies for a Decade of Slow Growth and Deflation.” Some portfolios he manages invest in currencies and commodities.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.