Trade-War Refugees Could Find Haven in Emerging Markets

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Investors alarmed by the intensifying trade dispute between the U.S. and China are fleeing emerging markets, but what they see as risk may turn out to be a haven.

It’s no accident that developing countries are feeling the fallout from concerns about China. Many investors venture into emerging markets through mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, and China features prominently in them. It accounts for a third of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, by far the largest country allocation.

Emerging-market stocks have tumbled since President Donald Trump first threatened to increase tariffs on Chinese goods earlier this month. The EM index is down 8.2% since May 5 through Monday, compared with a decline of 3.6% for the S&P 500 Index.

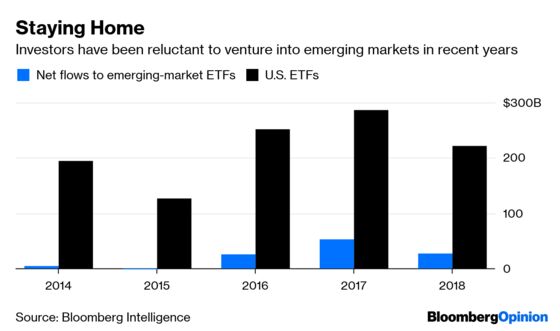

Investors were already leery of emerging markets. They poured 10 times more money into ETFs that invest in the U.S. than those that invest in emerging markets over the last five years through 2018, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

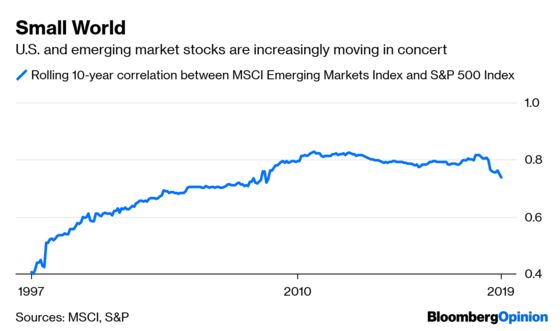

There’s no denying that emerging markets have been a letdown in recent years. They’re supposed to help diversify U.S. investors’ portfolios by zigging when U.S. stocks are zagging, but the correlation between U.S. and emerging market stocks has risen drastically since 1988, the first year for which performance numbers are available for emerging markets. The trailing 10-year correlation between the S&P 500 and the EM index rose to 0.74 in April from 0.41 in December 1997. (A correlation of 1 implies that two variables move perfectly in the same direction.)

More disappointing, diversification failed when investors needed it most. There have been two U.S. downturns since 1988, and emerging markets tumbled with the U.S. both times. The S&P 500 declined 44% from April 2000 to September 2002, including dividends, and the EM index fell 43%. The next time, the S&P 500 declined 51% from November 2007 to February 2009, while the EM index tumbled 61%.

Developing economies are also less stable than the U.S., so investors expect a premium for taking on that additional volatility. But the S&P 500 outpaced the EM index by 7.5 percentage points a year over the last 10 years through April, wiping out any premium over the last three decades. Both indexes have returned 10.7% a year since 1988.

Still, there are good reasons to think that emerging markets will hold up better than the U.S. during the next downturn — particularly if it’s sparked by deepening trade rifts — and that the premium from emerging markets will return.

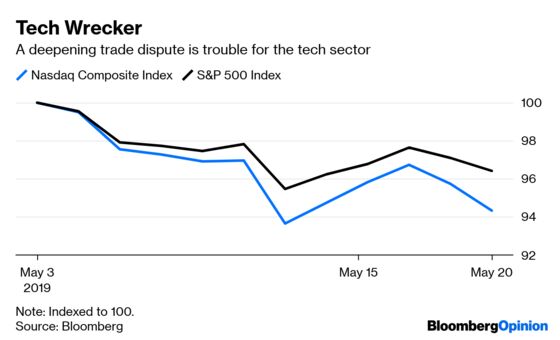

For one, the U.S. stock market is uniquely vulnerable to reversal, and not just because it’s among the most expensive stock markets in the world. It’s dominated by the technology sector, which makes up roughly 21% of the S&P 500, or 50% more than the next largest sector. As tech goes, in other words, so goes the market.

A prolonged trade dispute is trouble for the tech sector. Roughly 57% of its sales come from overseas, according to S&P, more than any other sector. By any measure, the tech sector is the first or second most expensive in the S&P 500, and those overseas sales are critical to holding up its lofty valuation. Declining revenue would almost certainly lead to lower earnings and sagging stock prices.

Investors have been treated to a dress rehearsal in recent days. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite Index led the declines from May 5 through Monday, falling 5.7% compared with a decline of 3.6% for the S&P 500. And it’s not the first time. During the previous trade flare-up at the end of last year, the Nasdaq fell 23% from October through Christmas Eve, compared with a decline of 19% for the S&P 500.

Emerging markets, on the other hand, have far less to lose because they’re already badly beaten down. By my preferred measure, U.S. stocks are twice as expensive as emerging-market ones. The EM index’s price-to-earnings ratio is 14, based on 10-year trailing average operating earnings per share, compared with 29 for the S&P 500.

That’s a different proposition than the one investors faced during the runup to the previous two downturns, when valuations were lofty around the world. In 2007, the P/E ratio for the S&P 500 was 29, while that of the EM index was 33. And in 1999, the S&P 500’s P/E ratio was a whopping 48. While the comparable P/E ratio for the EM index isn’t available because earnings data for emerging markets begins in 1995, the EM index nearly kept pace with the S&P 500 from 1988 to 1999, so it’s reasonable to assume that emerging-market stocks were no bargain, either. It’s no wonder investors had nowhere to hide during the subsequent downturns.

The longer-term outlook favors emerging markets, too. The drivers of future stock returns — earnings growth, dividend yield and change in valuation — all point to higher returns from emerging markets than the U.S. Dividend yields are already higher in emerging markets. Developing countries are also growing faster, which should mean higher earnings growth for their companies over time. And because emerging-market stocks are meaningfully cheaper than those in the U.S., there’s more room for their valuations to expand.

As the U.S.-China trade dispute deepens, don’t be surprised if emerging markets turn out to be the big winners.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.