Three Reasons the Saudi Attack Won’t Spike Oil Prices

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The oil market must be getting a sense of deja vu.

Now, as in September 2019, Yemen’s Houthi rebels have launched a missile attack on a major Saudi Arabian oil facility. Now, as in September 2019, Brent crude is flirting with $70 a barrel.

That’s where the resemblances end. The 2019 attack on the Abqaiq and Khurais oil processing facilities pushed crude prices up as much as 15% in a matter of hours. So far, Brent hasn’t increased more than 2.6%, to a 14-month high of $71.19.

Why the difference?

The first point to consider is that, unlike the Abqaiq-Khurais assault, the latest attack appears to have failed. The earlier strikes pulled 5% of crude from the global market — and although production was quickly restored and supplemented by flows from Saudi Arabia’s reserves, it was unclear in the initial days whether this would be possible.

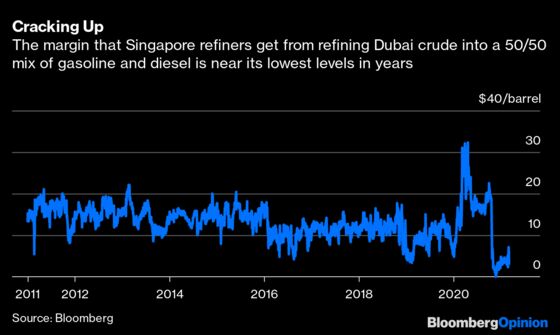

Oil price spikes aren’t generally the result of a fundamental shortage of crude. Instead, they come about as refiners rush to lock up supplies at any price amid uncertainty about whether they’ll be available a month hence. Refiners in Asia, the main destination for Saudi oil, are already getting some of the thinnest margins on Gulf oil in a decade. If supply is not going to be disrupted, they see little reason to pay over the odds.

Those thin margins help explain the second point. For all that oil prices have been on a roll in recent months, demand for oil products — the real driver of the value of crude — is recovering at a much more sedate pace. Those low refining crack spreads are an indication that fundamental demand isn’t nearly as strong as some participants in the crude market are betting.

Saudi Arabia itself seems to agree. The OPEC+ meeting that concluded Friday saw a surprise decision from Riyadh to continue withholding 1 million barrels a day of crude from the market for a third consecutive month in April. That will help to take the edge off supply increases by other cartel members.

The move, combined with the decision to raise prices for Asia and further squeeze those refiners, is an indication that Riyadh doesn’t expect America’s shale drillers to return to the market in a hurry, as my colleague Julian Lee has written. Instead, they’re hoping that selling less oil for more money, as opposed to more oil for less money, will be sufficient to satisfy a market that’s only gradually returning to normal.

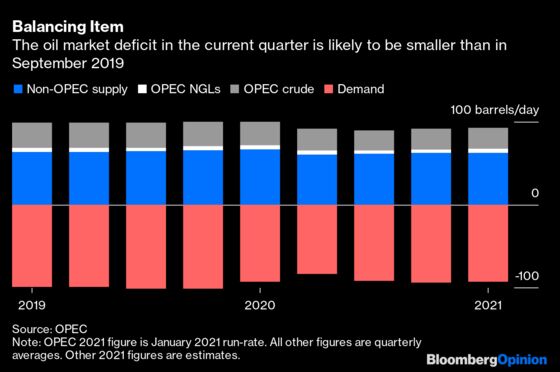

The estimates of supply and demand in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries’ latest monthly report back up that conclusion. In contrast to September 2019, when near-record demand of 100.89 million daily barrels left a deficit of about 2.2 million barrels in the market, demand this quarter is only likely to fall about 0.2 million barrels short of the levels that OPEC members were pumping in January. With Saudi Arabia’s own output hovering around 8.15 million barrels — less than two-thirds of the levels it could theoretically be producing, at a pinch — the world has little to fear.

Finally, there’s the situation in Yemen to consider. At the time of the 2019 Abqaiq-Khurais attack, the civil war that’s embroiled many of the Middle East’s major powers was still running hot — fueled by the Trump administration’s unwavering support for Saudi Arabia in the conflict. That strike came just a fortnight after more than 100 people were killed in an attack by the Saudi-led coalition on a prison complex in territory held by the Houthi rebels, who are supported by Saudi’s arch-rival Iran.

It didn’t seem unreasonable back then to expect that the attack would be the first shot in a further deterioration of a conflict where many of the world’s biggest oil producers are at loggerheads.

Matters look very different now. The U.S. under President Joe Biden is taking a distinctly cooler approach to Riyadh, removing the designation of the Houthis’ Ansar Allah movement as a terrorist group just weeks after it was applied by an outgoing Trump administration. Biden is also considering a halt on selling non-defensive weapons to Saudi Arabia, according a Reuters report last month.

Despite ongoing aggression as the Houthis try to seize more territory, there’s “renewed international momentum” behind a peace deal, Martin Griffiths, the United Nations’ special envoy for Yemen, said last month. In the 11 months since a Saudi ceasefire in the war last April, there have been 55 fatalities, compared to 549 in the year leading up to the 2019 attack, according to the Yemen Data Project.

It’s anyone’s guess whether that hopeful conclusion will play out after so many attempts at peace have failed. But the oil market, and the Middle East, is in a different place now to where it was 18 months ago. Crude’s sanguine approach to this latest attack seems justified.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.